In Who are my People?: Love, Violence, and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa Emmanuel Katangole lays out how possibilities for transformation begin in the gathering of people together in communities, small-scale though they may be. In the communities he describes, love positions as its diametric opposite the power of the western state interlopers, the developed nation-underwritten development agencies and development community, and of the successor of the colonial powers’ presence, the African states.

The communities in question emerge from their members’ shared recognition of the sacrificial suffering love of Jesus as portrayed in the Christian scriptures. Specifically, the Gospel stories’ portrayal of a love that calls those who follow Jesus to a self-sacrificing love for the good of others provide the vision that orients these communities. Katongole conveys the genesis of these communities through the theological portraitures he sets forth throughout the book. In these ways, Katongole’s book strikes me as an exercise in narrative theology that complements the work of another African ethicist and religious thinker, Charles Villa-Vincencio—entitled Walk with Us and Listen: Political Reconciliation in Africa. In this post, I’ll juxtapose the two books in order to bring the ethical significance of Katongole’s into greater relief. Comparing and contrasting the two will illuminate the vital, if unspoken, role that justice can and ought to play in the interaction of love and power in the vision of peaceable community set forth in Who Are My People? The result should illuminate themes and implications that are present in Katongole’s book, but hover in the background, and deserve to be brought into our discussion.

Reading Katongole with Villa-Vicencio

At the heart of Villa-Vicencio’s book was the instruction to would-be do-gooders and global crusaders from the U.S., the European Union, the International Community of political and economic elites, and the international NGO community to do what the title of the book commands: “walk with us and listen.” At the time, Villa-Vicencio described himself as partaking in the practice of “frank and fearless speech.” This purpose referred to Michel Foucault’s posthumously published lectures examining the Ancient Greek concept of Parrhesia which concerns “who is able to tell the truth, about what, with what consequences, and with what relations to power.” Foucault contrasted the Greek account with the predominant modern conception of “telling the truth” as an abstract speech act in which any person’s verbal assertion is perceived to be true in so far as it corresponds to a state of affairs in the world. The parrhetic understanding of “truth-telling” is a socially embodied and historically situated ethical practice that required the cultivation of the sensibilities and capacities of “truth-tellers.” Not just anyone can tell the truth on this account. “Truth-telling” requires understanding the context and historical circumstances, and critical assessment of the deeper causes and conditions of the state of affairs that one has in view. He explained, “[W]ith the question of the importance of telling the truth, knowing who is able to tell the truth, and knowing why we should tell the truth, we have the roots of what we could call the ‘critical’ tradition in the West” (170).

At one level, the “parrhetic” upshot of Villa-Vincencio’s exercise of “frank and fearless speech” was to say “walk with us and listen.” Or, to translate it into the ethical terms that infuse the title of that book—“Learn and practice the art of accompaniment. Accompany us! Walk along-side. Do not come to us to give us answers, or to rescue us. Often, we already know what we need. Enter into a relationship of mutuality with us. Open yourselves to the possibility that you will learn something that actually affects who you are and what you do, and makes some meaningful difference—some meaningful change—in who you are, and thus, how you understand and go about your efforts to aid others, to reduce suffering, and to help meet needs. Assist communities and societies invested in liberating and transforming themselves.” For Villa-Vicencio, any proposed aid or assistance or support from the international development or NGO communities must pass through the “eye of the needle” of the local (176). “The local” is not beyond scrutiny, of course, and must be engaged in a dialectical back-and-forth of critical dialogue. But proposed assistance, or administration of justice and/or humanitarianism from elsewhere (“from outside,” “from above,” or “top-down”) must always work in concert with, with critical input from, and indeed, seek to support, amplify, and center the agency—even follow the lead—of the people it aims to aid. We might say, it must pass through principles and practices of subsidiarity—the idea, with deep roots in Catholic social teaching, that matters should be handled at the level closest and most immediate to, and with input and guidance from, the people they most directly affect. Villa-Vicencio’s point was even stronger. He construed such subsidiarity as a kind of critical “brook of fire” that can bring to light and smelt away impurities like the hubris of pity or the rescuing mentality of a savior complex.

Paedeia is teachability that impacts who one is, what one is becoming, and how one sees and interacts with the world.

Katongole’s book opens up precisely the kind of spaces and occasions for encounter that Villa-Vicencio called for. That is, it opens up opportunities for readers outside these African contexts, readers in seminaries and universities, in schools of global development, in church and religious communities across the U.S., but elsewhere as well, to listen and follow along—to assume a posture of teachability in the deep and formative sense of another Greek concept, that of paedeia. This is not listening that seeks instruction for instrumental purposes so that one can better implement the technocratic expertise one is garnering in policy and rendering in development services. Here the catchphrase is: “I can integratively solve your problem.” Paedeia is teachability that impacts who one is, what one is becoming, and how one sees and interacts with the world.

Katongole’s book opens occasions for this kind of listening and teachability. This kind of walking along-side and accompaniment impacts who we—his readers—are, and what we are becoming. This must occur at multiple levels, including, and perhaps most importantly, in the development industry and development education contexts (such as, for example, Notre Dame’s very own Keough School of Global Affairs), if we aim to become teachers, researchers, and reflective practitioners oriented toward “global development” in a way that actually reflects the framework of integral human development. Katongole gives us this through a textured portraiture born of, and interwoven throughout with, theological reflection.

Interesting, and consistent with Villa-Vicencio’s effort, is Katongole’s willingness to engage in frank and fearless speech—a work of “truth telling.” Katongole tells his readers that the truth of the stories in the book are not put forward in any neutral sense. Rather, he forwards them on the basis of his conviction that “the truth of a story is judged by the reality it creates and the lives it shapes” (173). In other words, one can recognize and come to know the truth and integrity of these stories in virtue of the fruits that they bear (Matthew 7:15-20)—namely, the ways that they both model and inspire sacrificial love, and the cultivation of community oriented by such love. This approach speaks back to many audiences who, most likely, are in some way, at some level, captivated by—held captive to—the rejective myth about Africa. This is the myth that Africa is an essentially violent and uncivilized place from which nothing good can come, and thus in need of Western benevolence (172). Katongole identifies and debunks this myth. It is prevalent among even the most well-meaning of European and North American people though we may not be aware of it. Indeed, I would say that that myth is so pervasive that if we are not actively interrogating our thinking and presuppositions for traces of that myth, it is probably operative to some degree, and at some level, in the background. The book opens spaces for encountering these truthful stories and their effects, by “showing the possibility, indeed the reality, of an alternative—a nonviolent—Africa, one shaped by the story of God’s self-sacrificing love” (173).

Intriguingly, the central purpose and function of the book fits naturally with theology as an exercise of parrhesia, which, as I noted earlier, is a sustained exercise in the practices of truth-telling. This work operates in the spirit of critical theory that Foucault describes in his exposition of frank and fearless speech as a practice of truth-telling—a kind of “critical narrative theology” (though, clearly, without mimicking the actual genre and style of theoretical “critique”). Of course, Foucault saw the end point of such an enterprise as the exposition of the operations of “power,” whereas Katongole sees his end point as love.

Consider, for example, Katongole’s concept of “the violence of love.” The phrase does not mince words. We have here an instance of frank, fearless speaking as a component of the practice of truth-telling. The “violence of love” emerges as a logical extension of the portraiture of Christian activists throughout the book who are acting against the “devaluation and wanton sacrifice of African lives” (173). They discover that healing from “the burden of Africa’s history” entails suffering “the violence of love” in which the activists discover, embrace, and orient their work by the self-sacrificing love of God. This heals their own suffering, Katongole explains, but also “liberates them to invent new communities and practices through which they seek to heal, restore, and renew God’s love for other victims of violence” (174). In the Afterword, Katongole details some of the practices of community that embody and facilitate this transformation—practices like working in the fields together to grow crops, eating together, worshipping together, celebrating feast days and wedding ceremonies together, and building up friendships that can heal and transform the kinds of divisions and divisiveness that have been inflicted by Africa’s modernity.

With this, Katongole intentionally side-steps prescriptive social ethics, and even (as he anticipates some pointing out) “the task of ‘Christian social responsibility'” (174). He refuses to make specific claims about how to make Africa more peaceful and more democratic. Katongole says instead that he is working in a different kind of politics, in that he is refusing to deal with politics in relation to state power and instead engaging in politics understood as the ordering of bodies in space and time. This is politics that occurs in the form of relationships situated in community. They pertain to what those relationships require to cultivate, sustain self-sacrifice, and thereby, the transformation of harms and the transformation of community (172). This is the politics of love. As he quotes the former archbishop of Bukavu— “the only response to the excess of evil is the excess of love . . . the logic of the Gospel is a not a logic of power, but of the cross” (175).

The Necessity of Justice

As far as this goes, I find myself persuaded. I do wonder, however, if to end at this point and embrace the politics of “an excess of love” as, in effect, one horn of an apparent dilemma between the politics of love and the politics of social responsibility may tempt unwitting readers toward a kind of “ethical and political quietism”—that is, a quietism that risks refusing questions of “Christian social responsibility” altogether, instead embracing a (putatively) totalizingly different conception of the politics of love.

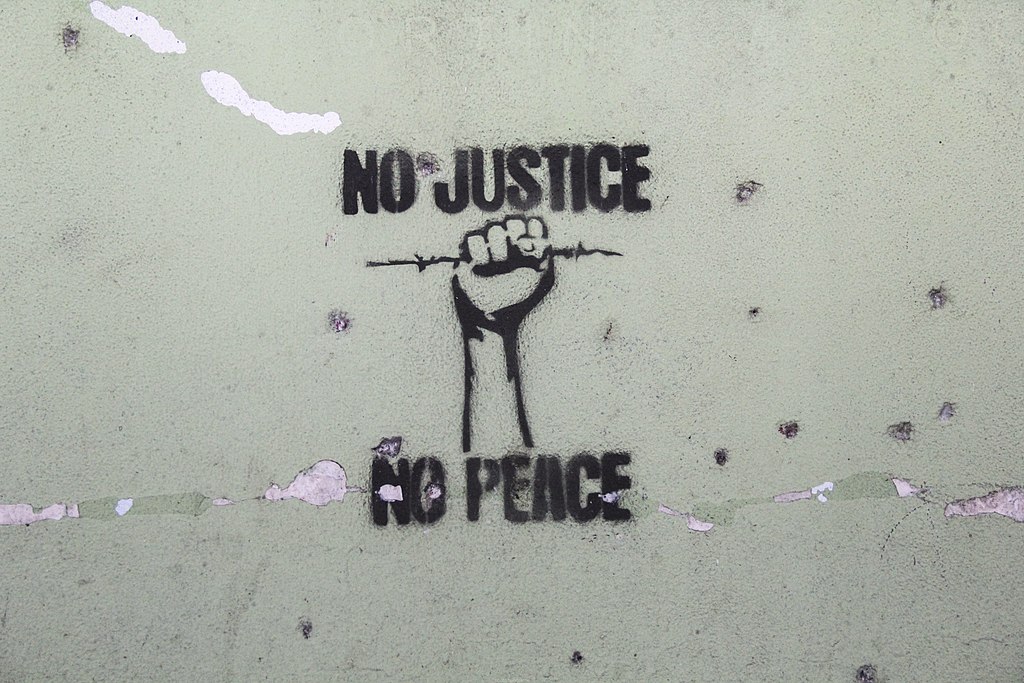

The risk is that leaving love and power as opponents may keep their untransformed essences intact. For the logic of the cross does not reject power, it transforms it, just like it transforms love as we humans know it and practice it. The exclusion of power in its untransformed version, ironically, therefore, leaves a third term occluded—a term that mediates love and power in virtue of the transformation of both terms by the logic of the cross. That mediating term is “justice.” In the portraitures that Katongole offers us justice is present, hovering over his exposition of the “violence of love and suffering.” But it is not explicitly spoken there.

Allow me to clarify by way of an example: the opposition of power and love by the former archbishop of Bakuva brought to my mind a pivotal point in the narrative arc of a class that I teach—a class entitled (apropos of many of the claims of Katongole’s book) “Love and Violence.” The class traces the impact of, and resistance to, French colonialism in Algeria, the impact of, and resistance to, British colonialism in India, and the influence of both these resistance movements upon the resistances marshalled by the civil rights movement in the U.S. In particular, I am reminded of the moment when Martin Luther King, Jr., in his appeal to the transformational capacity of the sacrificial love of Christ manifest through non-violent direct action ran headlong into a wall of refusal by many younger civil rights activists who believed it to be simply a “violence of love.” The response took its most pointed opposition in the form of Stokely Carmichael’s call for “Black power.” Power and love, Carmichael argued, were intrinsically opposed. You must choose one: either the violence of love or the violence of power. Carmichael vied for power.[1]

In the portraitures that Katongole offers us justice is present, hovering over his exposition of the ‘violence of love and suffering’ . . . but it bears making this explicit, integrating, and developing further.

King responded by refusing the terms of the opposition. He did this, textually, by reading theological mis-interpretations of Jesus’s teaching in the Gospels about love against Friedrich Nietzsche’s account of the will to power. In effect, King’s biblical analysis argued that the subsumption and transformation of both love and power in the agapic love at the heart of “the logic of the cross” transforms both, mediating them through the concept and practices of justice. He wrote, “What is needed is a realization that power without love is reckless and abusive, and that love without power is sentimental and anemic. Power at its best [power transformed by the logic of the cross, we might say] is love implementing the demands of justice. Justice at its best is love correcting everything that stands against love” (37–39).

I don’t see this at odds with the communally embodied politics of love that Katongole sets before his readers as the upshot of Who are My People? But I do think it bears making explicit, integrating, and developing further. And I invite his reflections on how he might articulate what these communities might have to say about the role of justice. This is especially important to interloping readers like myself, who aspire to listen, to accompany (as Villa-Vincencio urges us), and be taught in ways that might genuinely impact and alter who we are, how we engage with one another, and our work together here and now.

[1] This opposition erupted most starkly during Carmichael’s first invocation of “Black power” on the James Meredith march. For helpful exposition of this encounter, and its impact on the movement, see King in the Wilderness (2018; mins. 20–30).