This blog post draws on Rajbir Singh Judge’s insights in Prophetic Maharaja: Loss, Sovereignty, and the Sikh Tradition to reflect on Sikh feminist critique and its orientation toward egalitarianism as a horizon. In doing so, it explores how Sikh onto-epistemologies unsettle liberal conceptions of equality, critique, and justice.

Many revolutionary traditions in which my personal investments reside—be they the Sikh tradition or ethnic, feminist, queer or trans studies—were envisioned with the hope that one day they would be unnecessary. Here, the Sikh would submerge into the Guru (“Wisdom”), and ethnic, feminist, queer, and trans studies would become archaic with the end of racial cisheteropatriachy. However, the orientation towards their own dissolution has been subsumed by the demand for stable and essentialized coherence (for example, in the form of identity boundaries). Judge’s monograph resurrects that otherwise receded thread of revolutionary traditions by putting into question the terms and parameters that have arrested us.

One such parameter that I explore in this piece is the claim that Sikhi is egalitarian. Modernity’s demands to make Sikhi intelligible as a “religion” has led to such claiming that egalitarianism is definitive of Sikhi. Here, the distinction between principle and practice become sites on which this claim is defended and contested, animating forms of critique including critiques from Sikhi against systems of power and critiques of Sikhi in its complicities in systems of power. Without becoming stuck in these dualities, Judge’s scholarship extends Talal Asad’s theorization of tradition to offer insights into the limits of critique itself to invite an expansion in our conceptualization of justice.

Sikh Tradition and the Limits of Equality

Sikhi is the learning from the Guru, the struggles that start and end with the Guru, with the in-between space being the Sikh tradition. Judge and Asad claim that tradition is not a static essence marked by authenticity and contained within the grammar of historicity, but a never-ending site of contestation, struggle, and dispute that strives towards an impossible coherence. In other words, the Sikh tradition is always in formation, unfixed, always ever-becoming, and not easily located and contained within specific and essentialized sites like texts, beliefs, and practices. These are the sites around which secularism constructs and constrains religion. Judge’s theorization of tradition, then, troubles both the essentializing claim that Sikhi is egalitarian, and the division between principle and practice upon which the liberatory potential or failings of Sikhi are assessed.

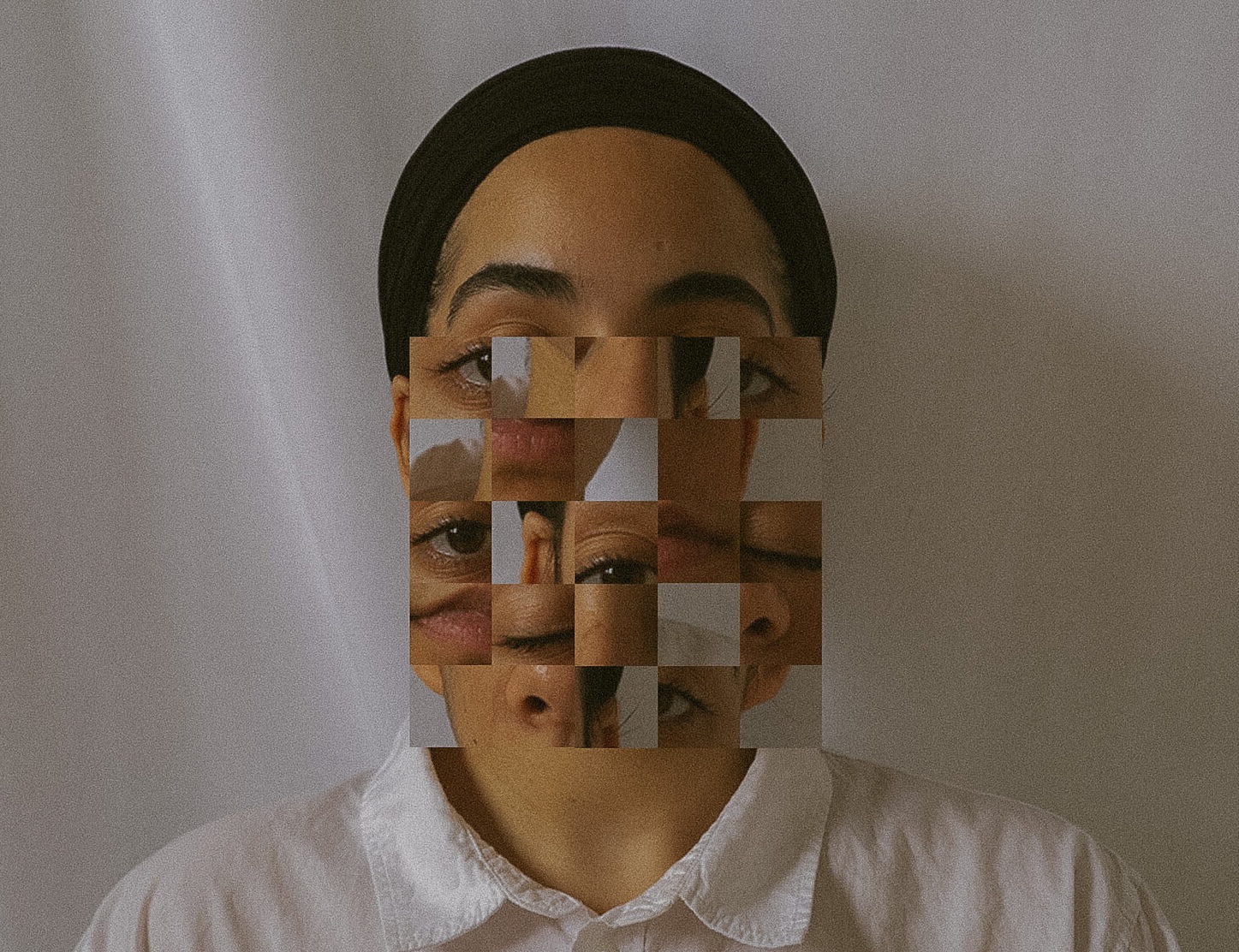

Sikh feminist critiques have powerfully illuminated the persistence of gender inequality in the tradition by exposing the gaps between principles and practices. However, as a non-binary Sikh who finds a home in neither the gender of “man” nor “woman,” the very category and system of gender is a manifestation of dubidhaa (duality). For me, gender is a site of violence and frustration, and not a site upon which I can conceptualize equality and liberation. Gender equality still presupposes the existence of gender as a system of essentialized categories.

Scholars such as Wendy Brown, Talal Asad, and Saba Mahmood reveal that equality— conceptualized through secular and liberal impulses—universalizes, essentializes, and assigns a permanence to the categories and terms we know today through which parity can be conceptualized. Sikh onto-epistemologies, however, are antagonistic to liberal conceptions of equality. Sikh onto-epistemologies teach the impermanence of the temporal (including categories like gender and caste), that stands in distinction from the stability and permanence of the Divine. Therefore, the Guru stresses that Naam, or Identification with the Divine (as opposed to that which is transient), is the means to liberation. The body, given its impermanence, serves as a transient vehicle towards, but not the source, for liberation. This differs significantly from many strands of feminist thought that emphasizes the body as a site of constitutive performances, subject formation, knowledge production, and accrual (or lack thereof) of freedom and rights.

Beyond Equality and Towards Gender Abolition

Liberation, under Sikh teachings, is not secured through the parity of temporal distinctions, but through Identification with, submission to, and submergence within the Divine. Sikh onto-epistemologies orient one away from procuring and securing a liberal and autonomous Self, which would only further entrench dubidhaa (duality) that marks separation from the Divine, and instead orient towards an un-becoming that seeks the death and dissolution of the Sikh, as identification with the Divine (i.e. Naam, Guru) transes (i.e. transgenders, transitions, transfigures, transmutates, transforms) the Sikh into the Guru. Throughout Bani (“utterance of the Guru”),[1] temporal scripts (including that of gender and caste) are evoked, challenged, destabilized, and redefined, and all temporal significations are re-evaluated, requalified, and redirected through the criterion of whether it leads one towards, or away, from the One Divine. Temporal significations like gender become a means through which one practices a form of subtraction—subtraction of the Self and the set of attachments that define the Self building on Judge’s discussion of community as subtraction. Such an understanding of gender as subtraction, as opposed to a set of accumulations, orients one towards transcending (or transing), as opposed to maintaining and seeking parity and coherence within, existing temporal significations.

Limitations of Critique

Sikhi’s ontological orientation towards subtraction and un-becoming reveals a limitation of critique. Michel Foucault and Judith Butler conceptualize critique as a “practice of freedom” from contemporary onto-epistemological conditions. However, in being bound to historicity, critique also risks further cementing the very limits it seeks to escape. The question, “What about women?” in Sikh feminist critique, for instance, seeks to locate and evaluate the subject of the woman marked by a sexed difference. Such a move risks reifying an essentialized rigidity based in biological determinism. Although the set of critiques produced by this question are generative in inspiring movements and tending to important gaps between principles and practices—a gap of absences and exclusions uncovered and filled by critique—they also risk (1) reproducing the very dualities the project of (Sikh) feminism seeks to transcend; and (2) reducing the always/never/un-becoming of Sikhi into a static repository to mine for answers or evaluate for perceived failures.

Judge’s work invites us to consider the limitations of investigating the gap between principles and practices as a “problem space.” It does so by rethinking the gap as a space of unfolding possibility where the ever-becoming Sikh tradition is being constantly negotiated, shaped, and unsettled. This shift enables a rethinking of critique outside of its reliance on loss and scarcity, towards a heuristic of abundance.

Insisting on Abundance

A few years ago, I created a Twitter (now X) account. One of my first tweets was that the Guru Sahibs were queer. Looking back, I was very naïve to not have expected the huge response and backlash the tweet garnered instantly on Sikh Twitter. This post is not intended to justify my tweet. I share it, rather, as a moment which exemplifies how an unverifiable speculation that evades questions of authenticity, which some would even regard as fiction, can attempt to rewrite a history in mobilizing and propagating a particular understanding of gender, sexuality, and Sikhi.

Such a speculation of Guru Sahibs being queer is not searching for queer and trans people in the Sikh tradition through a question like, “What about queers?” Instead, through destabilizing the attachments that define queerness and transness, or in other words, queering queerness and transing transness, the speculation is an insistence on seeing queer and trans people everywhere in Sikhi. In becoming unstuck from scarcity, absences and exclusions in which critique often operates, the unverifiable speculation is a practice of the heuristic of abundance in the words of Anjali Arondekar, or articulated through Sikh modes, a practice of chardi kala. Such speculations of Guru Sahibs being queer and trans are not only mobilized by different queer and trans Sikhs to affirm themselves or seek inclusion, but lay claim to the dynamic contingencies that define and undefine the Sikh tradition for our own making and shaping. The insistence on seeing queer and trans people everywhere is a refusal of the limits imposed by embodiment, representation, and historicity that Judge’s scholarship foregrounds. The insistence that queerness and transness are everywhere is an insistence that the Divine is everywhere.

What possibilities emerge from insisting on seeing women everywhere too, or even mapping womanhood onto Guru Sahibaan themselves? These provocations build on Sikh feminist critiques to re-examine and move beyond the horizon of gender equality. Judge’s interrogation of the carceral limits that both construct and capture us resurrect the orientation towards the dissolution of those limits—an orientation foundational not only to Sikh onto-epistemologies, but also to resistance traditions like that of ethnic, feminist, queer, and trans studies. Such a project unsettles ideas of justice reliant on liberal conceptions of equality and orient towards Self-annihilation and dissolution as opposed to Self-accumulation, procurity, and security. Such a project serves as a reminder that the path to liberation lies not in security—of Self, identities, and subjectivities—but in their un-becoming altogether.

This post is a modified version of a conference paper presented at Punjabs Symposium at the University of British Columbia, with the full paper forthcoming

[1] Definition indebted to the Guru Granth Sahib Project by the Sikh Research Institute.