In Pastoral Power, Clerical State: Pentecostalism, Gender, and Sexuality in Nigeria, Ebenezer Obadare takes a second step in his bold and original discussion of the nature of Pentecostalism and its influence and role in Nigerian society and in relation to the Nigerian state. The first step was taken in Pentecostal Republic: Religion and the Struggle for State Power (2018) wherein he discussed the role of Pentecostalism and the Pentecostal elite in Nigeria’s fourth republic. In Pastoral Power, Clerical State, the focus is on the pastor as figure and on the power that pastors seek to access, hold, and perform. The work is not bound by conventionalism—disciplinary or other—as it takes the Pentecostal pastors’ spheres of influence to extend across the nation’s “political, sexual, and cultural topography.” This scope allows Obadare to grasp the ultramodern—the merging of entities that were bounded and distinct within a modern framework (religious / secular)—fusion of delusionary ideals of democracy and recourse to religious frames of identity and power. Obadare’s rendering underscores the paradox between spiritual and political power and an ethical ideal of liberal democracy, one that will have impacts on our understanding of these concepts beyond the example of Nigeria.

At the heart of this book lies a discussion of the factors that contribute to and help us explain the indisputable rise of pastoral power in Nigeria, as well as around the globe. Importantly, he does not operate within the traditional/modern dichotomy that we often see in such works (either explaining the rise of Pentecostalism as a way of going back and drawing on traditional forms of power or seeing Pentecostalism as a modern phenomenon and a reflection of a millennial condition). He wrestles with large and far-reaching processes of change in Nigerian society such as the decline of the salience of the “Man of Letters,” which implies a change in the status of the intellectual, and the ascension of the “Man of God.” This process indicates the replacement of one cognitive framework with another and Obadare is astutely interested in and aware of the consequences of this shift. The central questions of the book come to rest on where power lies, what power is, and who can access and exercise power.

Pastoral Power opens by turning the question “why are so many young people becoming pastors”? upside down. This question, which has been key in my own work on Pentecostal pastors in Ghana, then becomes: “Why are not all young men becoming pastors” (xix)? This rhetorical maneuver is indicative of what Obadare sees as the prominence of pastoral power in contemporary Nigeria and its consequences on the operations of the Nigerian state. Much of what Obadare describes and observes around the Pentecostal pastor—a calling, eminence, prayers, prophecies, wealth—resonates with my own work on Pentecostal pastors in Ghana. My work has focused on the continuities between how Pentecostal pastors and traditional holders of power, whose authority cut across political and spiritual domains (such as chiefs) achieve, tap into, and hold spiritual power. What fascinates me about Obadare’s work is that he observes very similar processes among Nigerian Pentecostal pastors as Ghanaian ones when it comes to pastoral authority and its mechanisms, but reaches different conclusions and sees the wider future consequences of this change. What Obadare seems to indicate is that these issues should prompt us to ask big questions, such as: What happens to a liberal democracy when the locus of power moves from the institutions of the state to the thrones of Pentecostal pastors? What makes pastors unique and why are they capable of holding the kind of uberauthority that we see?

Obadare traces a significant shift in the history of power in Nigeria from the Man of Letters to the Man of God. This shift involved the breakdown of “emancipatory ideologies” (referencing Mary Kaldor, 46). Here he describes Major General Vatsa as an example of someone possessing intellectual flair and style. He was a soldier-poet who was defended and liked by people because of his intellectualism. This figure reminded me of Lomba, the prisoner-poet in Helon Habila’s Waiting for an Angel. Lomba is an aspiring intellectual and journalist who, under the military dictatorship of General Abacha, is living with the repercussions of his trade. After participating in an ‘anti-government’ demonstration, Lomba is imprisoned. While in prison, Lomba starts to write, first in secret, but is later discovered by a prison superintendent. After initial punishment, Lomba gets protection by writing ghost love poems for the prison superintendent who offers them to the woman he loves. The woman, it turns out, understands that the superintendent is not the true author of the poetry she has been given. Lomba, on his part, equally reflects upon the messages of the poems not being for her: “But how could I tell her that the message wasn’t really for her, or for anyone else? It was for myself, perhaps, written by me to my own soul, to every other soul, the collective soul of the universe” (28). Habila’s prisoner-poet masters the skills of the letter, but also the skills of performance and the words of love. He speaks to the existential soul of the universe. He is perhaps more than a Man of Letters.

The central questions of the book come to rest on where power lies, what power is, and who can access and exercise power.

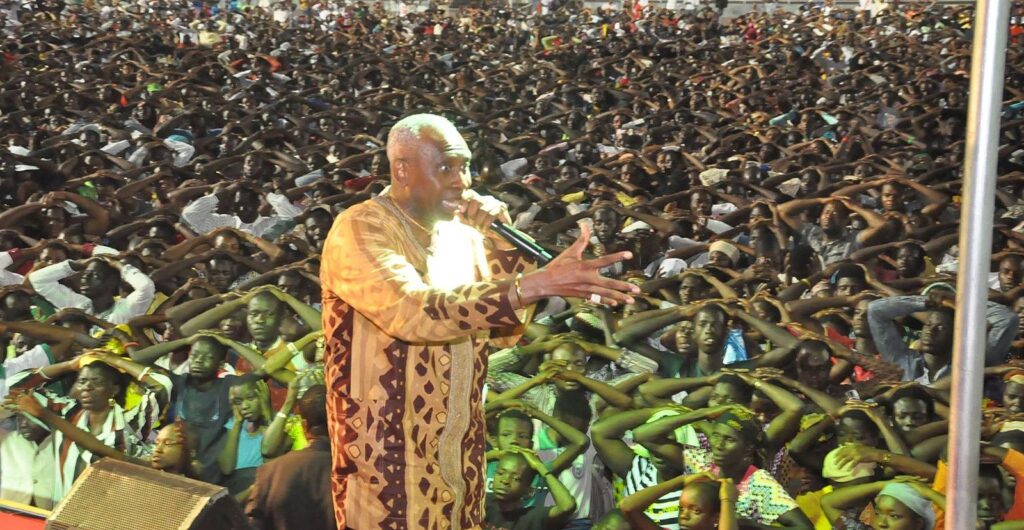

From here we can move to the pastor-poet. What is the pastor doing with words? The Man of God is also a Man of Words, though perhaps not “of letters” in the sense Obadare describes it. But surely he is a man of words. There is an eroticism to pastoral performativity as Obadare shows, but there is also one of performing knowledge. There is poetry in preaching, in being on stage and addressing an audience, whether that audience is in a church or in the street. We could say that the production and performance of texts (oral or written) conveys a status that stems from the recognition of these skills in society. As Stephanie Newell has shown in her study of Ghanaian popular fiction, the proverb is a way for authors to show that they are able to “quote from ‘outside’ texts in order to generate further text of their own” (11). Is there a way in which we can grasp the power of the Pentecostal pastor through this appropriation and tapping into an intellectual history that might be eroding, yet still holds potential for recognition?

With this, I return to the question of power raised by Obadare. Naminata Diabate, in her recent work Naked Agency: Genital Cursing and Biopolitics in Africa, discusses naked female protesting across Africa and through a variety of texts. She highlights naked protesting as an act of resistance as well as a site that exposes women to shame, death, and vulnerability. Diabate asks similar yet distinctive questions about the relationship between state power and spirituality as Obadare; they are different because she writes about women who engage in defiant disrobing as being in positions of power and vulnerability simultaneously and thereby points to the ambiguity that lies in holding certain forms of power, yet, similar because Diabate is interested in the relationship between liberal democracies and spirituality. Instead of asking how spiritual causality might undermine the fundamental principles of a liberal democracy, she wonders how the liberal modern state can accommodate the religious practices and traditions of a country. This is fundamentally a question about the “separation of the secular from the religious, which remains an ideal in our world with its promise of secularism-cum-freedom” (144). But what is the liberal democracy of today and in different contexts? This is an open question rather than one whose answer we should take for granted. Liberal democracy is certainly a yardstick and an ideal, but it is entangled with other not-so-liberal forces which cause us to reflect on the contradictions and non-exclusionary co-existence between mystical forces and political power, be it within democratic or other institutions. By defying the boundaries of discipline and genre, Obadare’s book pushes readers to ask this often neglected question about the nature of power in ostensible secular societies in our world today.