There is no use pretending that all we know about time and space, or rather history and geography, is more than anything else imaginative… imaginative geographical and historical knowledge.

–Edward Said, Orientalism (1978), 55.

Hamas’ October 7, 2023 killing of over 1200 people in Israeli communities bordering the Gaza Strip precipitated the vengeful and disproportionate Israeli state military assault of Gaza that has since taken many thousand more Palestinian lives (over 23,000 at the time of writing), and as a result mass displacement and a humanitarian crisis. Predictably, White American Christian Zionists explain and refract these events through the opportunist eschatological prism by which they see the world. Sean Durban explains that this is all part of God’s greater plan for his son, the messiah, to vanquish evil and bring about a millennium of Christian peace. These conclusions are especially difficult to read in the context of these events. Such imaginations of past and future are stuck on “orthogonal time,” a concept I borrow from Philip K. Dick to illustrate the ways in which such events are imagined to have always already happened as God’s future events for the apocalypse are set in time like a record on a turntable. Christian Zionists interpret the assault on Gaza as one such event, bumping the stylus forward as evidence of Christ’s imminent return. This temporality explains how Christian Zionist prophecies for Gaza naturalize these awful human—all too human—atrocities as fatalistic predetermination.

In this piece, and as a geographer of the apocalypse, I explore the ways space, and specifically landscape, is used as an instrument to (1) provide evidence of the imminence of Christ’s return, (2) to justify settler colonial erasure, and (3) reinforce Christian Zionist national identities. However, landscapes also open a liminal space for counter discourses. Ethnographic work with Christian Zionists reveals dissonate perspectives on the dominate discourse of erasure and colonization of Palestinian Gaza.

Most famous among the Christian Zionist commentators is Hal Lindsey. Lindsey is the author of the best-selling non-fiction book of the 1970s, The Late Great Planet Earth. Ever the Cold Warrior, Lindsey explained the 7/10 Hamas attack as follows: “I consider it a precursor to the war prophesied in Ezekiel 38 and 39—a war led by Russia and Iran. And make no mistake, Russia is tied to this.” His perspective of omniscient fatalism is typical of dispensational premillennialist theology—the dominant evangelical eschatology that states Christ will return to Israel prior to the millennium—in orthogonal time. He explains that “Christians should remember that this did not catch God by surprise… his plan continues.”

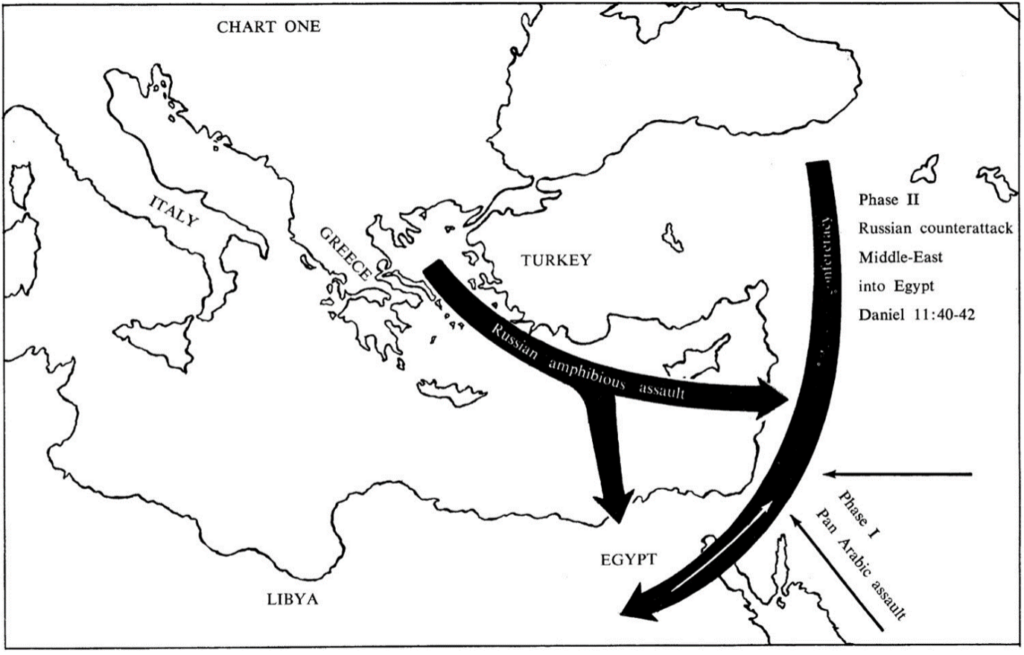

Lindsey’s position illustrates the centrality of not just time within the Christian Zionist imagination, but also space. Conceptualizations of space bring us back to Said’s words in the epigraph; this “imaginative geography” allows Christian Zionists to predict the future, and in doing so close off its other potentialities by attempting to re-make the world from their maps about it. Rendering the apocalypse cartographically potentializes the present and actualizes the future as a method of persuasion by rendering the apocalypse visible, exploiting the specious infallibility of cartography, and reducing future complexity to the apocalyptic abstraction that erases both Palestinian and Israeli agency and presence as mere objects of future history.

Christian Zionists are a powerful political lobby and cultural force in both American politics and geopolitics. Domestically, “64 percent of Evangelical Republicans say [Israel] matters ‘a lot’ compared with just 33 percent of non-Evangelical Republicans and 26 percent of all Americans.” In other words, given that 38 percent of Republican voters are evangelicals, Israel is not simply an evangelical concern but a Republican issue. Christian Zionists are a central election base—both for campaign contributions and votes—that might determine Donald Trump’s future return to the White House in 2024. Geopolitically, and as Stuart Croft argues, the Christian Right has developed its own views on foreign policy that challenge Realist, Liberal, and Marxist positions, what he terms “evangelical foreign policy.”

Lindsey famously focused on geopolitics to explain prophecy, and in so doing avoided the austere and certain failure of apocalyptic date-setting. Michel De Certeau explains this modern god-trick tactic of transposing space and time: “to be able to see (far into the distance) is also to be able to predict, to run ahead of time by reading space” (36). But this focus on space by Christian Zionists is not limited to the global scale of geopolitics. I ask what is lost in our analysis of Christian Zionism by focusing only on its famous (mostly men) authors, its Hal Lindseys?

My current book project, The Future is Foreign Country, focuses on the landscape pilgrimage sites of the apocalypse, visited by over 100,000 American Christian Zionists each year. I’ve been conducting an ethnography in Israel/Palestine since 2008, travelling with dozens of Christian Zionist pilgrimage groups. The places of interest, where the coaches tend to stop and the pilgrims disembark, are not the places one would expect for Christians, i.e., sites of Christ’s miracles, but are instead landscape vistas from which pilgrims can look out and, as Stephen Daniels once succinctly put it, “picture the nation” (5) with its strength, beauty, history, and future.

Upon these landscapes, American Christian Zionists revere, even consecrate, a group of people—Jews—with whom they do not and cannot belong, and a territorial state—Israel—from which they usually cannot gain citizenship. Here the territorial fetishization of “the Jew,” as Jonathon S. O’Donnell argues, is an antisemitic construction for the proper place for Jews in Israel against which all other Jews are out-of-place globalists. This nationalism is religious at its core, sprung from a set of interpretations of the Bible that identifies the Jewish return to Israel as a prophetic sign of the imminence of the apocalypse. This is religion as nationalism where nationalism is embedded in their theology as a religious rite and portended expectation.

Why Landscapes?

Pre-American Civil War, America was imagined as the New Jerusalem in stark distinction to England where these new Americans created a “geoeschatolic and geoapocalyptic consciousness… of the sacralization of an alternative place within the eschatology and apocalyptic drama of salvation and redemption” (Zakai 1992, 72). During the Reconstruction Era (1863-1877), however, Palestine figured prominently in American popular culture. In particular, pilgrimage narratives and guidebooks found a market far beyond the small number of Americans who actually crossed the sea. Pilgrimage to Palestine’s landscapes was one of self-imagination and renewal after the deep and divisive scars of the American Civil War. Palestine became these pilgrims’ new and unadulterated origin story, divorced from Europe and the troubles at home in America. As Hilton Obenzinger illustrates, “Travel to Palestine allowed Americans to read sacred geography…. While the persistent preoccupations with the Bible and biblical geography stood at the ideological core of American colonial expansion, actual travel to Palestine allowed Americans to contemplate biblical narratives at their source in order to reimagine—and even to reenact—ethno-religious national myths” (5). Palestinian landscapes were, as John Davis points out in his magisterial book, The Landscape of Belief, sacred spaces and the medium for American national self-definition for Protestants. They served as an anchor of morally pure beginnings.

This nationalism is religious at its core, sprung from a set of interpretations of the Bible that identifies the Jewish return to Israel as a prophetic sign of the imminence of the apocalypse.

Christian Zionists seek landscapes for three main reasons: (1) When 19th century White American Protestants arrived in Palestine, most of the urban sacred sites and buildings in Palestine were already claimed by non-Protestant groups. (2) Combined with the Protestant rejection of idolatry, such claimed space helped foment the rejection of monuments, buildings, and cities. Like early Jewish Zionism, the soil itself served a validating purpose. Davis explains “that Christians should put their trust in the soil of Palestine rather than the urban sites of Orthodox and Catholic tradition became a fundamental precept of most American activity in the region” (46). (3) Landscape creates an open space for Christian Zionists to perform their beliefs with abstract generality from afar, and without counter discourses of Palestinians. If the landscapes of Israel can be possessed through performative definition, then so too can the credentials of truth and faith be possessed, validated, and confirmed. To possess the landscape is to possess the truth.

These performative apocalyptic logics are not only a form of terra nullius (empty land), but also more specifically the imaginings of a spatial vacuity of Palestinians and Palestine, a vacuum domicilium (empty of inhabitants). This is what Christopher Pexa more generally frames as “settler colonialism’s exterminatory logic and its apocalyptic temporality” (4). Christian Zionist settler imaginaries find justification for colonization through the pre-emptive logic of terra nullius as orthogonal time. In other words, terra nullius is perceived as a rational pre-emptive logic of natural law with material consequences for appropriating inhabited lands.

Landscape is a masculinist visual representation and as such an ideological subject position, in this case, an imperial one taken up by a particularly powerful religio-political group. Scripting landscapes or “landscaping,” despite giving the illusion of being simply static and inert objects, are processes. I focus on the scripting and practices through which both landscapes and national subjectivities are constructed. Landscapes are often argued to be objects or stages upon which they are attributed meaning. And as meaning is applied to landscapes through various social mediums, they also naturalize operations of power by simplifying them through the erasure of that which does not fit their imaginings. In this case the presence of Palestinians. Landscaping is therefore an organizing principle that sustains mystification and is constructed through performances: dances, tears, prayers, sermons, gestures, tour guides, books, pamphlets, and various Bible translations. Landscape is not just iconographic or performative; it can produce a hegemonic experience.

Landscape is a masculinist visual representation and as such an ideological subject position, in this case, an imperial one taken up by a particularly powerful religio-political group.

Landscape is of course open to other future imaginings and while the Hal Lindseys in the movement hold significant interpretive cultural capital, my ethnographic work upon these landscapes, by embedding myself within pilgrimage tours, illustrated moments of dissonance with such dominant narratives. Nearly every day during Operation Cast Lead (2008–9), I travelled with Christian Zionists to Sderot, a town bordering Gaza. We delivered food to elderly residents as Kasam rockets regularly fell. At the end of each trip, we travelled to a landscape location that was about 100 meters from the official “press hill,” and 200 meters from the Gaza border. The edge of Gaza City was visible but blurred by the humidity and smoke. We were there to watch the war take place on the landscape, a kind of setting sun on our “benevolent” acts in Sderot.

The lookout was a theatrical performance which served as evidence for many pilgrims that God’s work was being done by the “the world’s most moral army,”a common legitimating phrase at the time invented by the Israeli Occupational Forces. Edward Said argued that all representation was of a theatrical nature, “the idea of representation is a theatrical one… a theatrical stage affixed to” (63) the national origin of the viewer. Despite seeing the various dense pluming puffs of white smoke that signified an Israeli bomb, it was the sound of the war that was most arresting and affecting; the sound of the bombs themselves that could be felt most acutely as the shock waves pushed through our bodies. It was here in this embodied landscape space that imaginations of Palestinian erasure were challenged.

I asked one of the American leaders of the trip what he thought about the ceasefire, and he replied: “The wars will never stop. My father said it would be the last war when I was a child. There have been five wars since. We must realize that there cannot be peace.” He then mimed a crash by bumping his fists together, and continued, “They will have their land we will have ours. Just separate, but not in peace…. Muslims are a people of death, and Jews and Christians are peoples of life.” This man was willing to concede that Palestinians did deserve land or at least that they would stubbornly never let it go. Such a concession is marginal, but nevertheless a discourse that challenges the dominate settler colonial discourse of Hal Lindsey’s erasure of Gaza as a prophetic event to make way for Christ’s return.

End Time

Israel’s 2023-24 military assault on Gazans is interpreted by Christian Zionists through an orthogonal apocalyptic lens that prophesizes a future settler colonialism of Gaza. The cultural capital of Hal Lindsey-type voices reinforces the eschatological fatalism that Christ’s return necessitates Palestinian erasure and hollowing out of Gaza. Lindsey and other powerful men like him, have, to borrow the words of Sacvan Bercovitch, converted “geography into eschatology.” As such, their imaginative geography of Palestinians being “out-of-place” to justify further atrocities as inevitable, even sanctioned by God, is awfully predictable. But as I theorize, the space of apocalypse does not operate just at the global geopolitical scale, but is crucially performative of the landscape. Their apocalyptic future is a foreign country where they advocate for a religious nationalism in a state of which they normally cannot become citizens. Such advocacy is predicated on a Christian eschatological discourse about a narrative of future affairs they believe to be infallible.

Christian Zionists thus attempt to performatively make the anticipated spatialization of the apocalypse tangible, and present, in the landscape through the insulated practice of American Christian Zionist pilgrimage in Israel/Palestine. Landscape is performed to tell a story about the virtual future, which becomes reinforced as everyday practice in the present by the tour guides, pastors, and the tour group. Crucial to understanding this co-constitution of landscape and nationalism is how it is performed not only as a place to see but also foresee. In a more recent article, Lindsey subtly conflates Palestinians with the devil. Quoting Ephesians 4:26–27 (NKJV) he helps his readers foresee and therefore justify Israel’s plans for Gaza: “do not let the sun go down on your wrath, nor give place to the devil.”

Landscape is performed to tell a story about the virtual future, which becomes reinforced as everyday practice in the present by the tour guides, pastors, and the tour group.

Ethically, the cultural “politics of hope” that Arjun Appadurai defines as a “politics of possibility over a politics of probability” is not always a progressive one (3). Anticipated spatializations of Israel are hopeful and eventually performative of exclusionary practices that mete-out Palestinians as at best racialized unwanted interlopers and at worst embodiments of evil as the Antichrist’s army. This said, the narrative is at times a contested one, though these spaces of pilgrimage are most often closed-off from transculturation due to the cloister of the bus and the oblique distance of landscape. It is here on the pilgrimage landscapes where discursive dissonance, and the inescapable question of the fate of people, namely Palestinians, are confronted by Christian Zionist pilgrims; where, as Rob Shields notes, “the ‘near,’ or the face-to-face and present-at-hand, [must confront] the ‘distant,’ the future, and the possible” (22).

I hope this piece encourages scholars of religion—and specifically apocalypse—to think about the geographies produced by their research subjects and how such spaces, in this case landscape, have co-constitutional affects. Landscape in this research reinforces Christian Zionist identities by providing evidence for a biblical apocalypse, and as such, the orthogonal time of apocalypse expects Palestinian erasure as a necessary precondition for Christ’s return and rule on Earth.

a very insightful analysis, and brings up the question of the role of “landscape” throughout western history, and art-history as a signifier of god-given ownership and control. As a synechdote of western christian/colonial hierachy of dominance over all creation. The hubris of claims of ownership over the matrix of life. A profoundly anti-Darwinian world view, but which forms the bedrock of our economic system and one that threatens all our survival now.

Much of what you say is interesting and needful to be said. But it is difficult to understand your work – to take it seriously even – when there is no reference to the Holocaust as a backdrop to the creation of the State of Israel. Elsewhere you also present Hamas as the democratically elected representatives of the Palestinians without mentioning that, since that 2007 election, they have brutally suppressed their own people and are explicitly dedicated to the destruction of Israel (and are funded by Iran to do exactly that). Have you ever asked yourself why you do that? You complain that Israel speaks of itself as a victim – without ever explaining why they actually do that (beyond the rockets from Hamas directed at Sderot.)