The Morehouse-Biden-Palestine Moment as Archetype of “Respectable” Protest

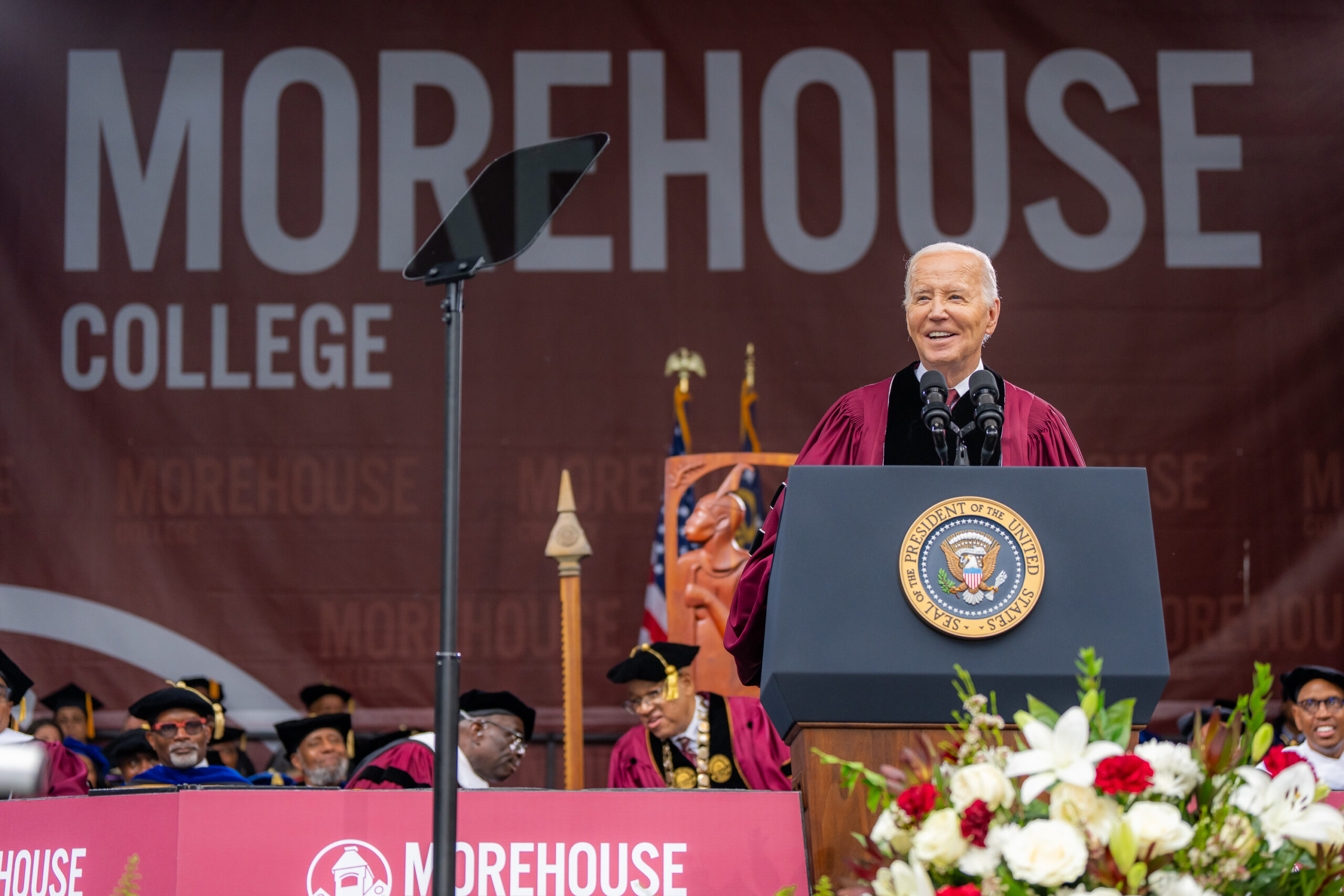

On Sunday, May 19, 2024, sitting US President, Joseph R. Biden delivered the commencement address at Morehouse College, an historically Black college in the heart of Atlanta, GA. Though the invitation to speak at the College’s 140thcommencement was extended in mid-2023, the Biden White House accepted the offer only a couple weeks prior to the 2024 ceremony. Between these two moments—the Morehouse College invitation and the President’s acceptance/ May 19th appearance—colleges and universities across the world had begun to erupt in civil resistance. The volume and intensity of these protests had not been seen since the anti-Vietnam War (and to a degree, the anti-Apartheid) student protests of the twentieth century. Student-led protests, labors strikes, and coalitional encampments had burst into existence to stand against the ongoing and (post-October 7) intensified Israeli military destruction of Palestinian life and land, demanding their universities to disclose financial portfolios and investments in the occupation and genocidal war and move toward divestment. These coalitional encampments, or tented communities emerging on college and university campuses, were often constituted by a vast array of student interests and affinity groups, which created for themselves micro maroon economies, that is, economies that recall the self-sustaining insurgent ecosystems of inspiration, strategy, and care that characterized Black resistance during any number of freedom struggles across the African Diaspora.

Immediately after Biden accepted the invitation to speak at the commencement, Morehouse faculty, alum, and students, reacted in widely different ways. Within each group, while some pleaded with the graduating class to show respect, not protest, and appreciate the opportunity to hear a sitting US president, others stood firmly within the historical lineage of Morehouse’s most famous graduate—Martin Luther King, Jr.—in indicting the College for welcoming a politician who belied, among other things, King’s vibrant critique of hyper-militarism. In some ways, students themselves led the dissenting critiques, particularly of both statist and racial uplift propositions. 2024 Morehouse graduate, Marq Riggins, and Spelman College rising Senior, Sydney Jael Wilson, note that after the accepted invitation was announced, “Biden’s team circled the college like a flock of vultures, frequenting our institutions for the social currency that comes with posturing themselves next to Black exceptionalism; he knows he’s at risk of losing our vote.” They go on to note, furthermore, that “Morehouse College President David A. Thomas’ decision to invite Biden illustrates a more extensive pattern where prioritizing profit and social currency takes precedence over listening to students and our families.”

Nevertheless, Biden’s decision to speak, in this moment, staked an important racial-political claim about the viability of Black dissent and, ultimately, Black knowledge-production. Stated differently, in a graduation cycle in which the President planned only two commencement appearances (West Point Military Academy and historically Black, Morehouse College) his advisors would almost certainly not greenlight travel to any institution—especially during a political moment shot through with campus unrest significantly because of the Biden Administration’s complicity in the genocide against Palestinians in Gaza—unless they, in their risk assessment, waged the institution posed little to no threat for viable dissent.

I foreground this vignette because it opens us into a set of ideas—presumptions—that help cohere arguments about racial Blackness, Black engagement with foreign policy, theological anthropology, and certainly, how historic Palestine and Palestinians exist in modern world imaginaries of global order and hierarchies of humanity. This key event of our time opens us into the ways that a significantly diminished protest, in a setting that many would expect to exemplify the moral protest tradition, directly resulted from a convergence of discursive forces functioning to silence Black dissent. Not insignificantly, King himself, an importantly non-static thinker—volleying between Black integrationist and Black radical commitments—can be considered an interesting conceptual prism through which to situate the convergence of discursive forces mobilized against Black dissent. The Morehouse-Biden-Palestine moment both re-inscribed and allowed fertile ground for certain Black voices (distinct from, but certainly alongside, “state” discourse) to traffic Black accommodationist sensibilities; though imperfect, the Black radical tradition continues to inspire and mechanize conceptual frameworks that challenge these very logics. Ultimately, I turn toward the sacred, claiming that formulations of Black sacrality can be considered among the conceptual tools—informed by Black radical thought—useful for thinking through unthinkable kinds of knowledges: in this case, the role of Palestine in the Black US imagination.

This key event of our time opens us into the ways that a significantly diminished protest, in a setting that many would expect to exemplify the moral protest tradition, directly resulted from a convergence of discursive forces functioning to silence Black dissent.

Black radical sacrality here is less about signaling any essentialist phenotypical category and more about offering a way to think through some of the conceptual and embodied interruptions and continuities that connote a contemporary marronage that calls back to some of the self-sustaining resistance communities of old, such as the Black Seminoles of Florida, the Maroons of Jamaica, or the famous Palmares of Portuguese Brazil.

King’s Tightrope

In the present-day, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s legacy in relation to Palestine-Israel is heavily contested. The now-notable October 2023 online dialogue between comedian Amy Schumer and Dr. Bernice King, daughter of the slain civil rights leader, was a microcosm of precisely this point. Schumer, weeks after the October 7 attack, shared on X (formerly Twitter) a decades-old video clip of MLK advocating for Israel’s right to exist, celebrating it as one of “the great outposts of democracy.” [Bernice] King, intervening against Schumer’s implication that her father would have therefore somehow supported Israel’s contemporary indiscriminate bombing of Gaza, noted, “my father was against antisemitism, as am I. He also believed militarism to be among the interconnected Triple Evils. I am certain he would call for Israel’s bombing of Palestinians to cease…” Bernice King and Amy Schumer, in this scene, represent the divergent, yet rather prominent ways that MLK’s legacy is taken up in relation to Palestine-Israel. In part, this somewhat fractured legacy is rooted in MLK’s own schismed, or at least antagonistic, thought. This is what Michael Fischbach notes as “the tightrope” that King walked: on the one hand, he was a man committed to both his American Jewish allies and the belief that the formation of Israel was an important culmination of a people’s democratic self-determination (which was not inconsistent, by the way, with any number of earlier Black nationalist/separatist thinkers in relation to political Zionism and later, Israel); on the other hand, Israel’s increasingly violent military expansion—especially during the 1967 Arab-Israeli War—made it progressively more difficult for King to stand, with integrity, on his anti-militarist, non-violence platform (81). He held these positions simultaneously, but was ever encouraged by his top aides—chiefly, Bayard Rustin—to not let any of his sympathies for Palestinians alienate or unsettle his American Jewish friends.

Indeed, King imbibed a kind of split consciousness on Palestine, between accommodationism with his American Jewish allies and a more progressive, anti-militarist sensibility. Recognizing this sometimes tensioned interplay between impulses opens a window into the ways that the policing of Black internationalist dissent is the result of a number of different discursive convergences—including nation-state discourses along with, as King signals, civic discourses internal (i.e., Black admonitions of other Black figures to act “acceptably”) and external (i.e., non-Black mobilizations of power to stoke Black fears) to the Black American collective psyche—all taking on a uniquely anti-Black racialized character.

Black Internationalist Dissent

To account for the discursive universe in which this Morehouse-Biden-Palestine moment circulated, I situate it within a broader trajectory of the management and mismanagement of Black internationalist thought.

In a keynote address, “The Challenge to Live in One World,” at the 1979 national meeting of the Palestine Human Rights Campaign, African American Christian leader, Jesse L. Jackson, noted, “in a cold war, it would be black people who lose their jobs and homes first; in a hot war, blacks would be the first to be drafted, put on the front lines, and the first to die.” His point was clear: Black folks have a vested interest in Middle East peace and justice. Jackson was among a cadre of Black religious leaders who, in late 1979, rushed to the public defense of then-Ambassador Andrew Young, after Young’s resignation from the Carter Administration for taking an “unauthorized” meeting with a PLO (Palestine Liberation Organization) official at the United Nations. He felt this point necessary to mention in the first place because, in real time, a host of Black and non-Black leaders scolded him, and others, that their focus must remain on the domestic concerns of civil rights, not international issues.

This was an historical moment in which Black activists and non-state actors partnered with state actors to police Black dissent. While “the question of Palestine” certainly was and remains an important flashpoint regarding the US management of Black internationalist dissent, it has been nestled within an enduring Cold War international-turned-domestic warmongering. Invoking the deep displeasure that some notable Black civil rights leaders had with African American activist, Paul Robeson’s increasingly leftist commitments and 1949 alignment with the Communist Party USA, Richard Iton notes, “Rustin [King’s adviser mentioned previously] would invoke an expanded version of the dirty laundry principle and contend, ‘there’s a sort of unwritten law that if you want to criticize the United States you do it at home; it’s a corollary of the business where you’re just a nigger if you stand up and criticize colored folks in front of white folks—it’s not done…We have to prove we’re patriotic’” (37).

This kind of intra-racial “housecleaning,” as Iton calls it, both mirrored State desires and scripted Black awareness into a broader US state need-desire “domesticate blackness and prevent racialized subjects from interacting across national borders, [as well as] disable leftist internationalism” (38). It is within this framing—coupled with the always-present potential for non-Black actors’ mobilizations of power, vis-à-vis the weaponization of antisemitism accusations—that one must frame present-day backlash against any number of decipherably Black thinkers and leaders articulating any affirmative position about Palestinian human rights, critique of disproportionate Israeli military force, or historic Palestine itself. For example: the scathing public reception that Marc Lamont Hill received following his 2018 speech at the UN’s International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People; the rescinding of Angela Davis’ human rights award from the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute the following year; the ad hominem attacks against Congresswoman Ilhan Omar in response to her critiques of the Israeli State; or most recently, the AIPAC-funded defeat of incumbent NY congressman, Jamaal Bowman. The list goes on.

Framing the management of Black internationalist dissent in this way accents analyses of the power already embedded within the US-based higher education ecosystem. With the increased corporatization and bureaucratization of US higher education, along with an increasingly production-driven neoliberal education model, necessarily comes increased securitization. Borders and boundaries are more heavily policed. Bodies are more surveilled. Dissent is more precarious. On some level, this is ideological terrain; particular kinds of ideas and epistemological starting points are snuffed out, made to die, while others are allowed to live. This is the case generally across the broad spectrum of US higher education, made all the more poignant in discourse about historic Palestine—typically under the guise of the “free exchange of ideas” and the “protection of civil liberties.” The 2024 suspension and investigation of White American political science professor, Jodi Dean, is a case-in-point. Dean’s punishment highlights the ways that the US higher education landscape manages pro-Palestine dissent broadly—a landscape that figures Black dissent, dissent from more racially precarious bodies, within it. Following an April 2024 blogpost, authored by Dean, discussing the liberationist sentiment felt by some in response to the October 7 Palestinian fighters (i.e., a particular idea assigned to be silenced by university knowledge-production structures), Dean’s institution condemned her remarks, removed her from the classroom, and launched an investigation to determine if the professor was in violation of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, prohibiting discrimination based on national origin (i.e., thus, sacrificing Dean in the name of protecting others’ civil liberties). In response to questions about if taking action against Dean infringed upon her own academic freedom protections, the institution’s vice president for marketing and communications noted their receiving direction from the US Department of Education “that tells us that in order to comply, we need to take action when we know or should know of a hostile environment based on national origin…In our preliminary estimation this could potentially fall within that.” In an unrelated moment, anthropologist Thomas Abowd notes, innumerable scenarios “underscore the rank hypocrisy that many schools—in their claims to racial equity and academic freedom—display when…a myriad other expressions of racism and harassment, institutional and noninstitutional, committed against Arabs, Muslims, African Americans, and other targeted groups” arise (183).

In other words, I’m suggesting that to wrestle with this Morehouse-Biden-Palestine moment is to simultaneously also wrestle with the management of a Black internationalist thought project, already presumed fugitive, within a US higher education landscape that is, at core, always already profoundly imperial (against both precarious and less-precarious bodies). Stated more thoroughly, the admonition directed toward Morehouse College students to respect and not protest the speech of a sitting US president; the college president prioritizing—in a somewhat Rustin-esque way—the social currency, proximity to power, and prestige that attend such optics of respect; and the same college president promising to shut down the commencement ceremony “on the spot” if severe disruptions (presumably, either protest or police intervention) were to occur during Biden’s remarks all point toward the discursive management of a Black internationalist dissent. Such dissent, and particularly Black dissent regarding Palestine, as Abowd and Dean signal, is necessarily racialized and bounded within a higher education political machine that securitizes and crushes the presumed fugitive to maintain order.

Black Radical Sacrality

If, as J. Kameron Carter suggests, a guiding principle of the Modern world is that the nation-state articulates itself and functions theologically—that is, deeply steeped in the “philosophical…[and] metaphysical claim to the rightness, the purity, the would-be gravity of the state as the telos of society…the horizon of order…[and that which] securitizes the world”—formulations of a Black sacrality come into view as a viable mode of resistance (170). According to Carter, “Black radical sacrality…unsettles, is ever poised to incite volatility with regimes” of the political as we know it (169). Black sacrality threatens the Modern world’s economy of racial capitalism insofar as this sacrality belies the violent oppositional hierarchies that structure it.

This Black radical sacrality—conceptually and embodied—is that un-articulable, ungrammaticized pulse that disrupts the terms of order. And it implicates how bodies show up in space and the epistemological groundings that such bodies, by showing up in space, build and trouble.

Black sacrality threatens the Modern world’s economy of racial capitalism insofar as this sacrality belies the violent oppositional hierarchies that structure it.

This is why emergences of encamped communities on college and university campuses—those campuses being, in an important way, the nuclei of nation-statist thought projects, and indeed, appendages of the state—have, of late, so profoundly disrupted university operations and respectability claims. The ungrammaticized, deviant excess always disrupts order en route to building new worlds. It is for this reason that historian and activist, Russell Rickford notes, of his institution’s Palestine solidarity encampment, “I witnessed a safe, dynamic, radically inclusive space…an expression of what civil rights workers once called ‘the beloved community,’ a society that enshrines the practice of fellowship, mutuality and agape love” amidst the institution’s “ongoing effort to criminalize solidarity with those the western world deems disposable [and] administrators portray[ing] the encampment…as a center of aggression and hatred.” Again, Black radical sacrality points us toward the conceptual and embodied interruptions that characterize contemporary resistance.

In the end, when President Biden delivered the 140th Morehouse College commencement address, there existed no mass-scale demonstration during the ceremony, no student encampment, but modest, yet no less important, individual student interventions: displays of Palestinian flags on graduation caps, backs turned during the Biden remarks, valedictory commentary calling for the assembly to remember its commitment to freedom dreams the world over—even within those whom we imagine as unimaginable.

Black dissent, particularly Black internationalist dissent, and even more specifically, Black internationalist dissent regarding historic Palestine must be considered within a particular matrix of boundary policing by various strata of disciplinary/disciplining knowledges—that are, at once, racialized and classed. Mobilizing tools from Black radical religious traditions can be a useful heuristic for imagining existences outside such death-dealing strictures.