The Moral Triangle by Sa’ed Atshan and Katharina Galor follows Israelis, Palestinians, and Germans in Berlin from a daring perspective: What if the German state would extend its moral responsibility from its Jewish victims to Palestinians, as victims of ongoing Israeli state-building/indirect victims of the Holocaust? What if the Holocaust and Nakba could be recognized in a causal relation carried through the lived or inherited experiences of Palestinians and Israelis living in the diaspora? Atshan and Galor demand precisely that when they argue “that the German-Israeli-Palestinian moral triangle requires an inclusionary ethos from all three parties that creates room for recognition of the Holocaust and Nakba” (24). In my discussion of Atshan and Galor’s book, I will intervene into the idea of perpetratorship, and in a next step point out the way Protestant morality infuses the current political landscape with regards to Muslims, Jews, and Germans. I see my interventions as pushing the authors’ proposal into the problem-space of secularism and its workings in history and memory.

The authors offer an accessible and inclusive language when describing the conundrums of Middle Easterners, specifically Palestinians, in trying to forge a dignified life in multiethnic Berlin. The book provides a panoramic view onto a range of concerns that the authors connect to the foundational violence of the Holocaust. These concerns include: “experiences of the Nakba, trajectories in pursuit of reconciliation, pathways of migration, policies toward refugees, integration of religious and ethnic minorities, racism, European politics and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict” (prologue). The authors’ approach is grounded in the framework of “multidirectional memory” as conceptualized by literary theorist Michael Rothberg whereby the memory of the Holocaust, and the attached traumas, can be juxtaposed with other violent events and experiences, such as the Nakba. This is done in order to “uncover […] historical relatedness [of Israel/Palestine to Germany] and work […] through the partial overlaps and conflicting claims that constitute the memory and terrain of politics” (xi).

Atshan and Galor uncover historical relatedness in this instance by asking a range of Palestinians, Germans, and Israelis about their opinions, lived experiences, and relation to official discourses about the Holocaust, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, antisemitism, and Islamophobia. While the interviewees are selected based on a seemingly narrow and clear categorization of national identity, the responses trouble such assumed identities and demonstrate how the interviewees position themselves vis-à-vis the issues interrogated. The authors refer to their interlocutors as “actors” (9), as if they had the agency to act and change the course of things. But agency is connected to a specific notion perpetratorship as I will explain below in more detail. They also state that most Palestinians preferred to stay anonymous because they feared repercussions for their statements. It becomes clear that all of these actors are not equal in society. I would add that Palestinians, much the same as most other German citizens of Middle Eastern descent, do not have the agency to act within politics and enact political change when it comes to these matters that concern them directly because they are considered dangerous Muslims before they are considered anything else. In other words, there is a situation in Germany and Europe in which the question of Palestine has become embroiled with the securitized “Muslim problem.” And perhaps this is the most important contribution of the book: it does not buy into this racializing politics, in which the Palestinian, as the quintessential figure of the Muslim, is a threat. Instead, The Moral Triangle claims a place of equality for Palestinians and brings them into a conversation that has been hitherto organized intimately between “the country of perpetrators or victims” (Chapter 2). The authors show that the victim narrative has a certain function within Israel and has also influenced Palestinian thinkers to reflect on being injured by the figure of the victim. Atshan and Galor open up a triangulated relationality through this figure and attach the Palestinian to the Israeli, as kind of a victim sibling. In Germany, however, this dynamic does not work so neatly. In fact, in my own research with civic education programs in Berlin the place of Palestinian or Muslim victimhood was usually denounced as “victim-competition” and ultimately antisemitic. Atshan and Galor in contrast, both operate with these terms and include the Palestinian in need of political recognition for his victimhood. And they also question these two broad categorizations by meticulously showing how their interlocutors identify or reject these perpetrator/victim categories, or in the case of Palestinians, become attached to these categories because they are the victims of the victims.

The categories of victimhood and perpetrator are more than models of national identification. They in fact establish an orientation toward the nation-state project after the Holocaust. In other words, because the Nazi state committed a crime against Jews and others, the German state after the Holocaust has committed itself to act in ways that would protect Jews or prevent other attacks on them, either as individuals or as a collective, as a diasporic community, or as citizens of the state of Israel. People residing in Germany may disagree with this privately, as Atshan and Galor show us. But these privately held opinions only show us how effective Holocaust memory is in structuring state-citizen relations in public. Allow me to refer to Hannah Arendt, who was dismayed about the idea of perpetratorship that would translate into collective guilt. She stated that in a country in which everyone is guilty, no one is guilty. For Arendt, there were concrete perpetrators and criminals who had to be tried for their individual actions. According to her, guilt was neither inheritable nor something that could be collectively shared. Claiming guilt collectively, according to Arendt, just offered a cover for those perpetrators who were indeed guilty of specific crimes. For Arendt, then, guilt could be only valid at a symbolic level. But there is something that Arendt overlooks, as do Atshan and Galor in a certain respect. Beyond how people actually feel or actually think, perpetratorship is decoupled from historical and personal action and enables more than a national or symbolic identity as Atshan and Galor conceptualize it. Perpetratorship allows for repair and maintenance (Wiedergutmachung) of German liberal democracy.

The categories of victimhood and perpetrator are more than models of national identification. They in fact establish an orientation toward the nation-state project after the Holocaust.

Claiming historical perpetratorship has shaped the language and practice of citizenship. In my own research on memory politics and secularism, my interlocutors in German civic education usually stated: “Of course these teenagers are not guilty of any of those crimes. But they have a responsibility for liberal democracy. They need to be able to prevent such crimes from happening again.” In other words, the grand narrative of perpetratorship is a crucial element of citizenship, inculcated and practiced in non-formal civic education programs, but also in formal high school education and in ritualized Holocaust commemorations that work as a form of public pedagogy. This inculcation enables participation in public as a German citizen and ultimately shapes political agency. The ideal German citizen has cultivated the right capacities and sensibilities towards the figure of the Jew, liberal democracy, and the secular state after the Holocaust. And although these morally charged relations grow out of a particular German-European-Western Christian history, they thoroughly inform the universal category of the rights-bearing citizen.

Historical perpetratorship is an inclusive concept in Germany and it includes the figure of the Jew as a sacrificial victim. Once one submits to perpetratorship, it enables and empowers them to act and be recognized as a rightful citizen. In my observations with Middle Eastern civic educators, their recognition as rightful citizens went beyond the history of the Holocaust and Germany. They had to condemn Palestinian violence and omit the larger structure of occupation. Bringing up the structural issue of occupation could be read as criticism of Israel, especially when one was not similarly criticizing any other Middle Eastern country involved in comparable crimes. Palestinians, specifically those who trained to become civic educators, had to do the double labor of proving that they were not antisemitic by giving up their claims on Palestine as ancestral land. Clinging onto an idea of Palestine or pushing for a right to return was discussed in civic education and among antisemitism watchgroups as an attack against the Jewish character of Israel, even a potential genocide in planning. In other words, Palestinians could not simply naturalize into Germanhood by way of perpetratorship. Even if Palestinians naturalized into historical German perpetratorship, they appear as current and potential future perpetrators in German discourse, lacking the right conduct vis-à-vis the figure of the Jew. It was then only a matter of time until they were exposed as antisemites. This exposure, however, was usually talked about in depoliticizing terms as harboring sentiments of raw Islamist hatred, integral to Muslims since the days of the Prophet. By way of a discourse on “Muslim Antisemitism,” similar to, but different from “Christian Antijudaism,” Palestinians have become the central subjects of Islamic extremism prevention projects.

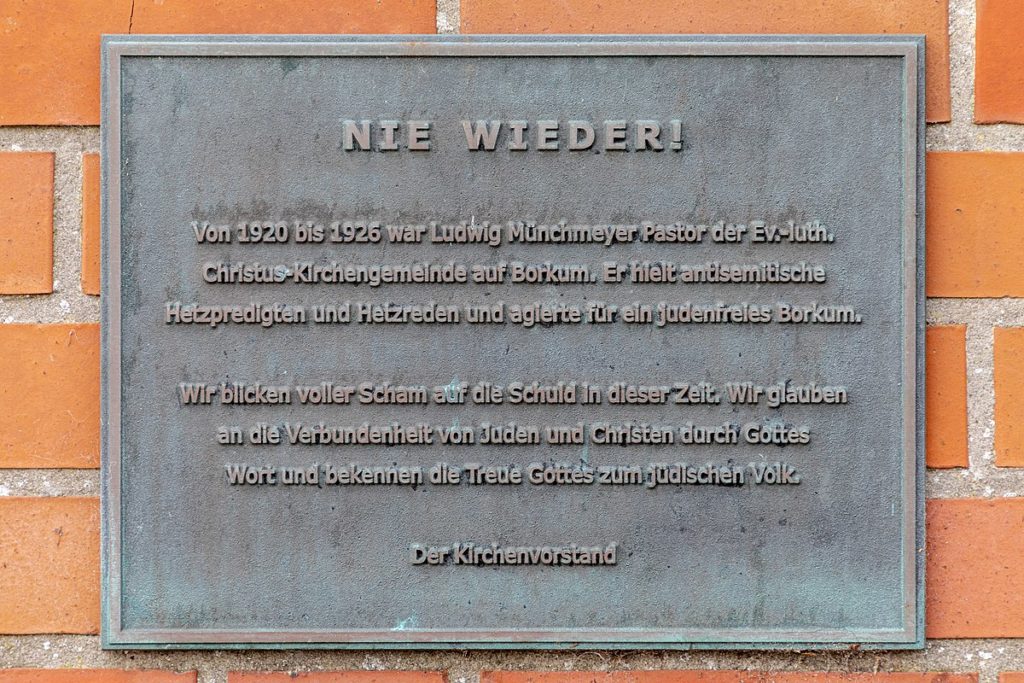

Institutionally, the position of the perpetrator was first claimed by the German Protestant Church (EKD). Lothar Kreyssig, a former judge and a major figure in the EKD, regarded the Holocaust as “a sin against God’s creation” and pushed for atonement beyond the church and interreligious dialogue. Atonement meant working through one’s burdened conscience by doing voluntary service in Israel and with victims of Nazi crimes. According to church records, however, the first volunteers in the early 1960s neither felt guilty nor particularly burdened. Some had not even reflected on their parents’ complicity in Nazi crimes when they started their service. Yet the volunteer service and the value attached to it connected them to a bigger cause of repair after genocide. Again, certain practices and forms of labor, such as caring for Holocaust survivors in an Israeli kibbutz, allowed for the shaping of sensibilities and capacities towards oneself as a person with a greater mission and a citizen oriented towards creating a more moral state after the Holocaust in relation to the figure of the Jew.

The history of post-Holocaust Germany and German-Jewish relations cannot be fully grasped without understanding the wider efforts of the Protestant Church. These efforts include the re-organization and incorporation of certain religious concepts, such as conscience, into the post-war German constitution. But they also include the EKD’s perception of the figure of the Jew as a human who had been killed, but who was also reborn in the state of Israel, thus giving Germans a second chance to make up for their sins against God. And although many Berliners might think of themselves as atheist, non-religious, or secular, as Atshan and Galor describe in their book, this conviction only speaks to how well certain religious concepts have been converted into the secular state’s foundational elements and public institutions. This conversion process includes the figures and elements through which the Holocaust remains experientially sacred, unique, and exceptional, and constitutes a civic responsibility for the creation of a better secular state and a liberal democracy.

The history of post-Holocaust Germany and German-Jewish relations cannot be fully grasped without understanding the wider efforts of the Protestant Church.

What I have hitherto discussed is how certain Protestant morals have found entrance into secular institutions and have helped overcome a political-moral impasse defined by a narrow notion of genocidal guilt. My intention is not to decry an incomplete secularism, but to point out how religious reason, memory politics, and citizenship are enmeshed in the secular state with far reaching consequences as to who belongs. In this context Germaness already is equated with the secular—because of a neat conversion of traditionally Christian practices through public, legal, and educational procedures—Muslims are equated with the religious, and being Jewish ambiguously designates in most cases belonging to the state of Israel. Consider for example how antisemitism and Islamophobia are understood by one of the interviewees: “Anti-Semitism is hatred of the state of Israel and Islamophobia is hatred of a religion” (105). Atshan and Galor describe this as a conflation of antisemitism with criticism of Israel. I would rather contend that this is the aforementioned successful conversion of Protestant morals within the secular state. The success lies in how it universalizes its own particularity and attracts pedagogical practices, integration, and reformist Islamic politics for an ethnically and religiously heterogeneous population of former migrants and refugees.

The task before us as scholars then is to understand and explain how Germans became secular, Middle Easterners/Palestinians became Muslim, and Jews came to stand for the state of Israel after the Holocaust. And what is the role of Holocaust memory in secular conversion? Perhaps this is work that must be done on scholarly terms before Atshan and Galor’s vision of mutual recognition among Germans, Israelis, and Palestinians can become true.