On September 16, 2022, twenty-two-year-old Mahsa Amini died in custody in Tehran following her arrest by the Guidance Patrol (Gasht-e Ershad). Instantly, her death became a rallying cry for young Iranian women against the existing political order that has imposed and maintains unyielding patriarchal restrictions on women’s legal rights and life choices. Captured in the mantra Zan, Zendegi, Āzādi (“Women, Life, Liberty”), the protests that began in Saqqez, Mahsa Amini’s hometown in Iran’s Kurdish north, soon became a nation-wide revolt against the Islamic Republic. The judiciary, the police, and the state-controlled media made an absurd attempt to attribute Ms. Amini’s death to natural causes. But why, people asked, was a young woman in police custody for failing to observe an arbitrary dress code in the first place?

The speed with which the protests spread throughout the country and were radicalized into an anti-regime revolt surprised the government. They were ill-prepared to respond, as was evidenced in its brutal show of force on the streets and in the rapidly unfolding propaganda war inside and outside the country. Finally, after two weeks of mystifying silence, the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, spoke. He blamed Western powers for fomenting unrest in the country and manipulating “naïve young people” into executing a sinister plot to overthrow the Islamic Republic. He refused to acknowledge the deep and palpable discontent over a variety of issues that had motivated the unrest. The increasing pauperization of people from all walks of life (caused partly by the crippling US-led sanctions); the anguish and hopelessness of a new generation that feels deeply alienated from the culture and values that ruling classes promote; the feeling of abandonment of marginalized regions, particularly Kurdistan and Baluchistan; rampant corruption that plagues the state agencies and top officials; and many other legitimate grievances of the nation have found no place in the state’s narrative of the revolts that have shaken the foundations of the Islamic Republic.

It is true that there are regional and global state actors who are trying to instrumentalize and exploit these protests in order to topple the Islamic Republic or to coerce the regime in Tehran into submitting to the demands of western powers. But the regime’s failure to acknowledge the legitimate grievances of an entire population will only deepen the protesters’ antagonism and further polarize the political situation.

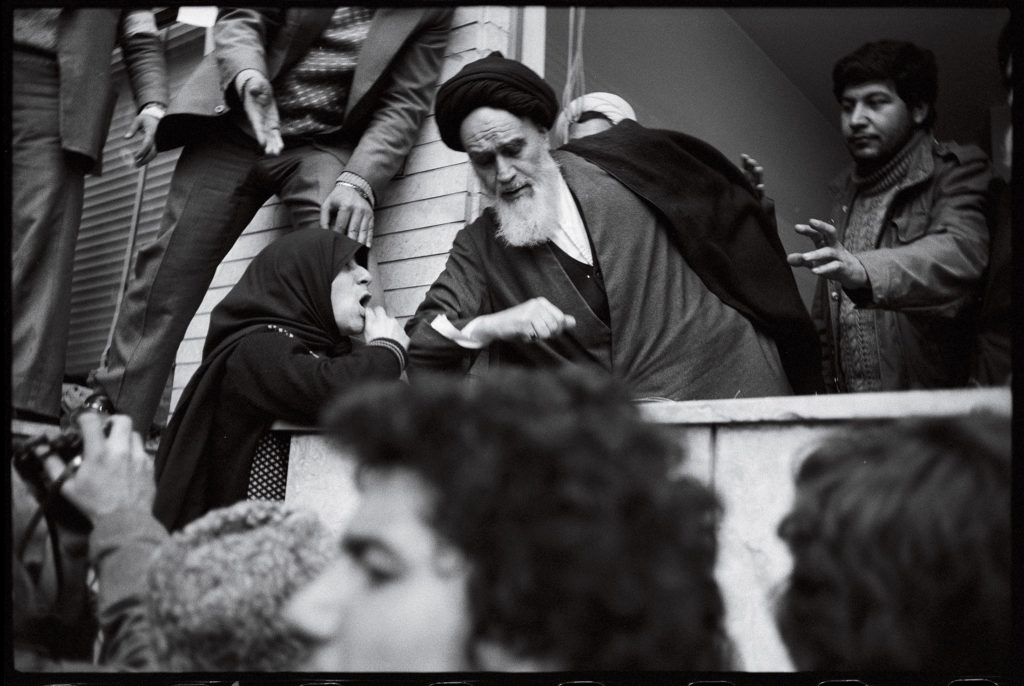

The ongoing uprisings in Iran might ultimately end the experiment that was Islamic Republicanism. Unlike the common analyses that attribute the current events in Iran to either the total failure of the Islamic revolution or an instance of the impossibility of the Islamic state, I see the present revolt, ironically, as the realization of Islamic Republicanism. I use the term “realization” in a dialectical sense to suggest that the Islamic Republic negates itself through its own realization. In other words, the republican process—with references to teachings of Islam—unleashed massive participation of otherwise excluded social groups (particularly women) who would eventually question the dominant ideology that made that participation possible. This dialectical process began to unfold from the moment when Ayatollah Khomeini, for the first time during his exile in Paris in 1978, spoke of the establishment of an Islamic Republic. He made that declaration with the full consciousness of the essence of republicanism that lies in the principle of peoples’ sovereignty and their right to self-determination.

Unlike the common analyses that attribute the current events in Iran to either the total failure of the Islamic revolution or an instance of the impossibility of the Islamic state, I see the present revolt, ironically, as the realization of Islamic Republicanism.

From the very beginning of the establishment of the Islamic Republic in 1979, the conflicting institutional sources of sovereignty and legitimacy of the state became a contested political predicament. The Majlis (Parliament), the office of the presidency, the prime minister’s office, the office of the velāyat-e faqih (the guardianship of the jurist), and the Guardian Council all struggled to reconcile the sovereignty of the people with the Islamic character of the new republic. The constitution of the Islamic Republic recognized the right of self-determination, so long as its exercise does not contradict the principles of Islamic creeds. In practice, however, rather than a point of reference, Islam became a contested body of religious discourses with competing interpretations from inside and outside of clerical establishment. The framers of the constitution believed that once they established the form of governance, Islam would shape its substance. They wanted to establish a religious state by sacralizing politics, making Islam the point of reference for good politics; in practice they secularized religion, making the state’s expediencies the arbiter of the right interpretations of Islam. In other words, rather than a religious state, the clerical establishment created a state religion. By doing so, not only did they suppress voices of dissent from outside of the polity, but they also marginalized the seminaries and the seminarians and turned them into an appendix to the state and its interests.

The struggle over who could legitimately claim authority in interpreting Islam and its teachings on good governance gave rise to a reformist movement in the 1990s. Now lay intellectuals, lawyers, journalists, women activists, young seminarians, and other social groups claimed authority in interpreting Islam and in defining the meaning of the right of self-determination and its relation to Islamic principles. The reform movement that culminated in the two-term presidency of Mohammad Khatami (1997–2005) emerged from the unintended consequence of making Islam the point of reference for good governance. The remarkable mobility of women, their unprecedented access to education and health care, and their demands for equal rights, particularly in the cases of divorce, children’s custody, and inheritance, had a constitutive significance in this movement.

Although the reformists theorized their movement on the principle of “bargaining from the top and pressuring from the bottom,” for the most part, they remained a movement for participation in political power. Civil society—the publication of private newspapers, the strong publishing industry, the formation of vibrant intellectual circles, and various forms of women’s groups (reading groups, sports, professional associations)—flourished in precarious terms. Nevertheless, it generated and sustained a deep sense of transformative power among people of all walks of life. Despite the omnipresence of state repression, this collective sense of empowerment and civic engagement grew rhizomatically, without a vertical hierarchical structure. The state, with its complex and oversized system of intelligence gathering and surveillance, remained suspicious of all political parties, professional associations, and other formal institutions that could possibly mobilize their constituents for any form of political and/or civil action. But these informal and loosely connected, or disconnected, networks grew exponentially among a new generation that cared little for the revolutionary mores and values that defined both the ruling classes and those who had hitherto defied them.

The economic crises that were perpetuated by the US’ crippling sanctions, which had intensified during the two-term presidency of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005–2013), hastened the separation and antagonism between the state and civil society. Rampant corruption and virulent crony capitalism, disguised as the privatization project of the state-owned industry, increasingly deepened this antagonism. To reframe this growing discontent, to justify its own patriarchal repression, the state adopted an instrumental relation with Islam, labeling all expressions of discontent conspiracies against Islam and the sovereignty of the Islamic Republic.

Since its inception, there has been a major divide within the polity of the Islamic Republic between those who advocate a totalitarian ideology that operates based on the notion of insider/outsider and friend vs. enemy, and a disappearing minority who promote something similar to an agonistic democracy. The latter aims to turn enemies into adversaries and transform all antagonisms into agonism. The final nail in the coffin of the agonistic tendency was the election of Ebrahim Raisi to the presidency in 2021. Raisi prevailed in an election in which the Guardian Council disqualified all other viable candidates from running. Popular participation was the lowest in the forty-year history of the republic. The conservatives cynically seized all three branches of the government and took a major step toward the realization of their totalitarian dreams.

Women stand at the forefront, driving this nationwide revolt because there exists the deepest contradiction between their massive participation in social affairs (artistic-cultural production, journalism, education, civic engagement) and the patriarchal laws and denigrating regulations that seek to govern their bodies and appearances.

The Supreme Leader, along with the Guardian Council, tried in vain to delink the regime’s legitimacy to electoral participation. For the first time since its inception, the absence of competing factions in elections created a clear rupture between the Islamic Republic’s polity and its constituents. By monopolizing all three branches of the government, the conservatives created a state that defined itself in the self/other binary terms without leaving any institutional forms for the expression of dissent for the “other.”

The protests of the past few months demonstrate how this binary of self/other was translated into open hostilities and seemingly unresolvable antagonisms fought on the streets of every urban center in the country. Women stand at the forefront, driving this nationwide revolt because there exists the deepest contradiction between their massive participation in social affairs (artistic-cultural production, journalism, education, civic engagement) and the patriarchal laws and denigrating regulations that seek to govern their bodies and appearances. We do not know whether this movement will lead to regime change or a major overhaul of the existing order. Those at the top might succeed in using the uprising to entrench the authority of the Islamic Republic through a brutal reign of terror. We all hope fervently that the latter does not come to pass. But one thing is certain as Iranian women have demonstrated these past several months: A nation that has inherited a revolutionary spirit and has perpetuated it through collective expressions of discontent over the past four decades will not easily submit to naked repression, regardless of how it is exercised or justified.

*I would like to thank Julie Livingston for her comments on an earlier version of this essay.