Kashmir has a special place in the South Asian imagination not only because of the famed beauty of its landscape but also because of its unique religious and cultural history. The idea of Kashmir as a “special place” is an old one. We encounter it in pre-modern Sanskrit religious and literary culture, Persian histories, political discourse in postcolonial South Asia, and in modern popular cultural forms such as Bollywood film. The historian Ronald Inden has made a compelling case that it is these imaginings of Kashmir as a special place that account for the intractability and intransigence of India and Pakistan on Kashmir.[1] What is, and remains, special about Kashmir is a unique vision of religious pluralism in its religious and cultural history that has not yet found political articulation.

The modern State of Jammu and Kashmir, which the Indian government has reorganized through an act of the Indian Parliament (Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, 2019), was born as a feudatory, princely State of British India ruled by the Dogra dynasty of Jammu (1846–1947). It emerged at the end of the Anglo-Sikh war with military help from the British. The idea of Kashmir as a “special place” had already been in place when it was mobilized by Kashmiri Muslim nationalists from the 1920s to the 1940s to challenge the legitimacy of Dogra rule. But it was only in the 1930s, after the Dogra army massacred protesting Kashmiris, that the latter launched a popular movement for sovereignty that received support from prominent Indian nationalists agitating against the British colonial rule. Such nationalists included Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, and Maulana Azad. By the late 1930s, many Kashmiri Hindus had joined Kashmiri Muslims in this struggle for the idea that Kashmir belonged to Kashmiris. This movement was interrupted by the Partition of British India in 1947 and rapidly unfolding events in its aftermath (communal strife which spread from Punjab into the Jammu region, the revolt against the Dogra State in Poonch, and the arrival of the Indian Army in Kashmir on October 26, 1947 to ward off Muslim tribal irregulars from Western Pakistan backed by the Pakistan Army that had entered Kashmir, and the first India-Pakistan war of 1947–48). Even though the post-Partition sectarian strife receded, it morphed into a political dispute between India and Pakistan over Kashmir.

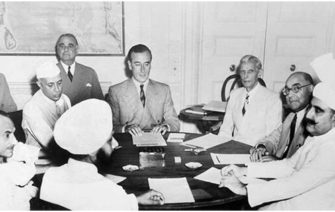

In 1948, the State of Jammu and Kashmir was effectively divided by the first India-Pakistan war into a Pakistani-controlled territory and an Indian-controlled territory (most of the Kashmiri-speaking region, however, passed into Indian control). The Kashmiri nationalists had close relations with the leaders of the Indian freedom struggle (Mahatma Gandhi had visited Kashmir just before India’s Partition in the hopes of reconciling different views in Kashmir) and the idea of Kashmir as a “special place” with unique political aspirations was recognized in the form of the special provisions of Article 370 of the Indian Constitution. The terms of Kashmir’s membership in the Indian union were debated for five months among the Kashmiri and the Indian leadership in 1949, with the result that Jammu and Kashmir emerged as an autonomous State within the union of India. Yet the aspirations for full independence never died down in Kashmir (even as pro-Pakistan politics were increasingly suppressed within Indian-controlled Jammu and Kashmir ) and tensions emerged as early as 1953 when Kashmir’s nationalist leader, Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah, was jailed for allegedly seeking independence. The arrest of Kashmir’s most popular leader, Sheikh Abdullah, in 1953 also started the process of diluting Kashmir’s autonomy and slowly eroding Article 370. Such slow dilution was evident as early as 1963, when India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, spoke of “the gradual erosion” of Article 370. These events, seen as a political betrayal by Kashmiris, were also the culmination of a strong protest movement by the Hindu nationalists in India who considered these special provisions to be nothing other than yet another shameful capitulation by the ruling Indian National Congress Party to Muslims.

It is this Hindu nationalist view which has triumphed in the Indian government’s recent decision to completely and unilaterally abrogate Article 370. Such a decision was made ostensibly to help better fight a decades-old anti-India insurgency in Kashmir (an insurgency which has for the most part been inconsequential, but has been significant enough to disrupt political processes and keep the Indian Army engaged in the region now for more than thirty years). It is far from clear if cancelling Kashmiri autonomy can boost India’s counterinsurgency efforts and produce a decisive victory, but it is possible that it could return Kashmir to being narrowly imagined as a site of sectarian Hindu-Muslim conflict. One might even wonder if a return to the original provisions of Article 370 that had been negotiated in 1949 and were demanded by Sheikh Abdullah’s son, Farooq Abdullah, on his return to power in 1996, could have stopped this insurgency in its tracks at a time when it was struggling militarily.

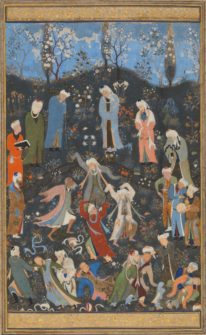

One ends up in Kashmir where one started off in the first place. The political claims of both India and Pakistan on Kashmir not only go back to the moment of the creation of the two States in 1947, but also pass through the history and memory of the sectarian conflict between the Hindus and Muslims of South Asia, stretching back even further in history (in the case of Kashmir, to the fourteenth century). The genesis of the Kashmir conflict, and its trajectory in the late twentieth century, is a complex subject. But what is clear enough is the symbolic centrality of both the religion and culture of Kashmir to India and Pakistan. Such culture includes shared sacred spaces such as astaans, Kashmiri Sufiyana music, folk forms such as Kashmiri folk theatre (band pather) and Kashmiri folk music (chhaker), Kashmiri poetry, and Kashmiri arts and crafts. These would be claimed by Pakistan as a distinctive Indo-Muslim culture and by India as an example of its secular and plural traditions. Religion and culture have been fundamental to shaping the idea of Kashmir as a “special place.” But even though the Hindu and Muslim religious cultures in India and Pakistan offer us fantasies of Kashmir as either a sacred Hindu space or a lost Muslim paradise, the actual Kashmiri Hindu and Muslim religious culture affirms Kashmir as a heterodox and plural spiritual space.

For most Kashmiris themselves, it is the vision of a Kashmiri spirituality expressed as a continuum of Saiva-bhakti-Sufi-tantric ideas in Kashmir’s literary culture—in particular, the mystical poetry of the Saiva saint-poet Lal Ded and the Muslim Sufi poet, Nund Rishi—that best articulates the idea of Kashmir as a place, even a “special place.” A close reading of these saint-poets reveals a deep commitment to religious tolerance, caste equality, and philosophical thought which gets taken up by generations of Kashmiri poets and historians, and informs Kashmiri ideas of the self. The Saiva, Lal Ded, uses Sufi metaphors and the Sufi, Nund Rishi, uses Saiva metaphors (Nund Rishi calls the Quran sahaja, the simple yet blissful path). This recognition, and the recognition of the political desires that flow from it, has become difficult to express in light of the rise in sectarian tensions in Kashmir and the rest of South Asia since the 1990s. It is likely to become even more difficult after the controversial end to Kashmir’s residual autonomy under an already eroded Article 370. One could dismiss this vision of Kashmiri religious pluralism as disguised nationalist rhetoric (as studies on “Kashmiriyat” or Kashmiriness as a nationalist, or subnationalist, ideology purportedly promoted by the Indian State often do), but these ideas about religion and culture are not only affirmed by many Kashmiri Hindus and Muslims. They also represent the possibility of a future that rejects sectarian understandings of Kashmir’s multiform past. But Kashmiri religious pluralism (philosophical thought of Lal Ded and Nund Rishi, in particular) also poses a challenge to official versions of Indian secularism that have not been able to ward off the threat of majoritarianism and offers a different way of thinking the secular (much like the thinking of Kabir and Gandhi) as an enabler of respect for and dialogue across religious traditions. The Saiva-Sufi milieu in Kashmir is one of the many distinctive moments of religious pluralism in South Asia. A deeper understanding of this religious pluralism can open up new pathways for thinking about democracy and freedom not just in Kashmir but also in the rest of South Asia. This idea of Kashmir is impossible to abrogate.

*Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the positions or policies of Ashoka University.

[1] See, for several essays which touch upon this theme, Aparna Rao and T N Madan, eds., The Valley of Kashmir: The Making and Unmaking of a Composite Culture? (New Delhi: Manohar, 2008). See especially the essay by Ronald Inden.