March 2020 was a time of unprecedented change and innovation for religious organizations around the world. The global COVID-19 pandemic resulted in many countries shutting down their borders and banning public gatherings to combat the spread of the virus. As a result, hundreds of places of worship were forced to close their doors and quickly find alternative ways to meet and conduct services. As public lock-downs and quarantines continued into April, the challenges were heighted for religious groups. Rituals surrounding Jewish celebrations of Passover and Christian observances for Holy Week and Easter had to be reinvented. The inability of religious communities to meet in person over these key religious holidays raised questions about how well religious groups are able to adapt to such unexpected changes. What would it mean for religious groups if social distancing continued to be required and enforced? What becomes of religion if its traditional practices and regular forms of gathering are not allowed?

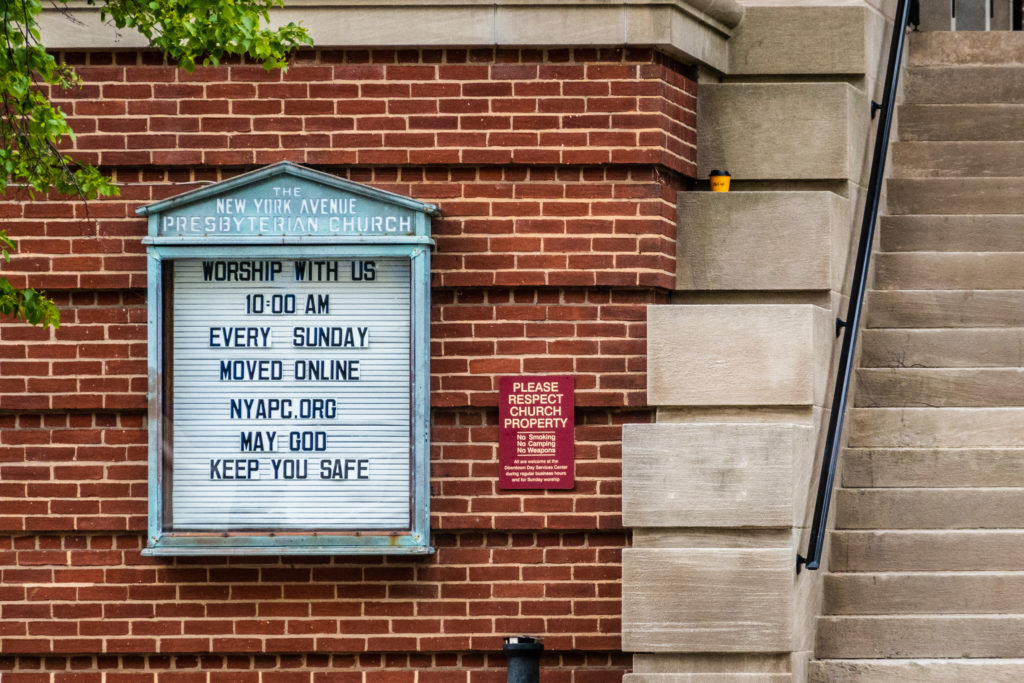

The common response during the pandemic in America was for Christian churches to opt for technology-based solutions. This meant transitioning away from long established embodied practices that take place in the church building such as communal prayer, celebratory meals, or responsive readings to disembodied practices that take place on digital platforms. Several studies conducted during this time by Church groups and researchers found pastors were both overwhelmed and excited by these changes.

New Challenges

A survey of 1573 pastors conducted by a collaboration of church consultancy groups found many churches conducted online services for the first time ever in March 2020. Because of this, most pastors (41%) reported feeling ill-equipped to use the digital tools required, such as internet streaming and video conferencing. A follow-up survey by the same group in April reported that while pastors were beginning to get a handle on the new technologies, they were now becoming aware that doing church online did not automatically create opportunities for community engagement, which many of their members were missing. This shows that churches’ sudden dependency on technology did not come without problems for leaders.

Many religious leaders have seen this forced engagement with new technology as an unplanned challenge. The Barna Group, a Christian resource and research company, found that nearly half of pastors (48%) said that the unexpected growth and “innovation around technology” in their churches made them uncomfortable. Barna’s online survey of 434 Protestant Senior Pastors found that most of leaders’ time in the first few weeks of the pandemic were taken up with implementing technology. The transition from in-person services to online gatherings required hours of impromptu media trainings, the redesigning of sanctuary spaces to accommodate cameras, and the modification of traditional service structures and liturgy.

In addition, leaders suggested that trying to bridge the physical separation between members and leaders during worship through technology-driven alternatives has, rather than overcome such social distance, simply created another form of it. Some noted that worshiping online seemed to encourage members to be passive-observers, rather than engaged worshipers.

Transferring, Translating, and Transforming Worship

Yet, this critique of online spaces—that it encourages observation over interactivity—could also be made of many churches offline worship services. This is something I argue in a recent essay from an eBook collection that brings religious leaders and scholars of digital religion together to reflect on how the COVID-19 Pandemic might be altering religious practice in America. Here I assert that American religious culture since the mid-20th century has become primarily event-focused, where pastors spend most of their time planning and preparing for their weekly worship service. This observation is also echoed in the research data cited above, as pastors ranked the Sunday worship service and it’s adaptation at this time as their number one priority.

My essay discusses three common approaches to doing church online that I observed over a month of participant-observation in over 60 online Protestant and Catholic worship services. These include transfer, translation, and transformation approaches to services.

The transfer or broadcast approach attempts to replicate the traditional service online as closely as possible. Here most churches set up a single camera in the center of an empty sanctuary and attempt to get a wide angle shot of a service conducted as if it were any other gathering.

Other church leaders focused on translating and adapting certain elements of their traditional in-person services, such as communal singing or liturgical readings, into a space constrained by camera angles or the screen dimensions of the streaming platform.

Yet, just as the pastor’s survey noted, these transfer and translation strategies still created challenges for religious leaders. 59% of pastors surveyed felt online church services struggled to create opportunities for social engagement and conversation within the community. This concern was also voiced by Christian religious leaders outside America who are seeking to build and adapt to a new form of remote worship and church life. In March 2020, a survey of Australian pastors similarly found church leaders were concerned with how to build community in this new environment in ways that encouraged true connectivity over feelings of isolation.

These concerns point to the third strategy, transforming church, an approach taken up by only few of the churches I observed. It is here where we can see the sense of excitement amongst pastors that the survey pointed toward. In this approach, religious leaders reflected both on what new forms of gathering digital technology could facilitate, as well as on the needs voiced by their members for online experiences that would help support and build community. Transforming worship online looked like a pastor turning his home study into a space where he could give nightly “fireside chats” to his church, responding to the issues people had voiced to him that day via phone calls, emails, and texts. It also looked like a minister in England using her blog to get people to participate in a group conversation about the themes to be addressed in her sermon, integrating their responses, photos, and artwork into the actual service.

I argue that this moment, when churches are forced to abandon old models and reimagine church in new ways, creates a unique opportunity for religious communities to reflect on the needs of people in contemporary society. The COVID-19 pandemic offers an important moment for religious institutions to re-evaluate whether or not their models of ministry truly meet people’s desires for community and connection with others. This is not only true of Christian communities; Jewish and Muslim groups have also been forced to re-evaluate their practices concerning valued religious traditions and gatherings at this time, from communities turning Passover into a mediated family affair to cancelling the hajj to holy sites in Saudi Arabia.

These disruptions also point to the event-based focus of many contemporary religious groups. Individuals’ commitment to religious rituals and public gatherings remain the central way most religious institutions evaluate religious commitment.

The use of ritual events as the basis for determining community membership or investment defines community primarily in institutional and place-based terms. Yet, over the last three decades people’s understanding and practice of community have shifted. The reality is that most people, both religious and non-religious, experience and live out community as a social network of relations. This means that for most people, community is something that is dynamic and changeable, holds multiple connections, and is determined by personal needs and choices. This idea of the network challenges most religious group understanding and practices of the community.

Conclusion

This global pandemic calls into question religious group’s dependence on older models of community and religious commitment. It also amplifies the need for awareness that religious communities now function on a network model, a fact made visible by offering mediated online interactions and gatherings. Being forced from offline religion to online religion requires religious communities to reconsider what it means to truly practice and live out community and their faith. Recognizing this moment will help religious groups not only create viable worship-based social distancing strategies. It will allow them to consider the changes that are in store for them as they play catch-up to these societal changes, and seek to prepare for a post-pandemic future for religion.

Suggested Readings:

Campbell, Heidi A and Osteen, Sophia (2020). Research Summaries and Lessons on Doing Religion and Church Online. Available electronically from https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/handle/1969.1/187806

- This is a synopsis of ten research articles written by Professor Heidi Campbell over the past two decades addressing important Issues of how religious communities use the internet,

Hutchings, Timothy (2017). Creating Church Online: Ritual, Community and New Media. New York: Routledge.

- This book is a comparative study of how online churches function as internet-based Christian communities and traces three specific groups’ development and engagement over a ten year period.

Campbell, Heidi A (2020). The Distanced Church: Reflection on Doing Church Online. Available electronically from https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/handle/1969.1/187891

- This eBook of 30 essays brings ministers and priests, reflecting on their moving religious service online during the COVID-19 pandemic, into conversation with media studies scholars and theologians who have extensive research expertise in religion online so they can learn from one another.