One of the most curious aspects of the Christchurch mosque shootings is that Brenton Tarrant, the twenty-nine-year-old accused of murdering fifty-one worshippers, was so obsessed with medieval Crusades, as well as early modern clashes between Christian Europe and the Ottoman Empire. Yet Tarrant’s infatuation with these histories, coupled with his unstinting allegiance to far-right extremism, is by no stretch unique. Indeed, Tarrant’s embrace of “ethno-nationalism” echoes the re-emergence in the 1910s of the U.S.-based Ku Klux Klan, which modeled its uniform on the confraternity robes worn by members of Christian religious orders hundreds of years earlier. White supremacists reasserted this dubious connection to the Catholic Church in the 1960s when the murderous White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan named its Mississippi chapter after religious military orders such as the Knights Templar and the Knights Hospitallers.

Despite Tarrant’s seeming awareness of these and other futile attempts to rationalize racial violence via Christianity, his overall comprehension of the particulars and nuances of European social history is utterly lacking. A telling excerpt suggesting as much from Tarrant’s seventy-four-page manifesto posted online prior to the Christchurch massacre stated: “The origins of my language is European, my culture is European, my political beliefs are European, my philosophical beliefs are European, my identity is European and, most importantly, my blood is European.” As these distorted ascriptions illustrate, Tarrant’s identification with the continent posits that the essence of European heritage is effectively synonymous with his own mythic “whiteness.”

This worldview, and its intersections with a global uptick in racial terrorism, underscores how deadly the resurgence of white supremacy and separatism in recent years has become. And in the case of Europe, various manifestations of these patterns suggest the risk of failing to acknowledge the continent’s history of social, cultural, religious, and ethnic diversity.

Despite marked progress since the 1960s in dismantling colonial frameworks as the predominant mode for interpreting European history—including Europe in the world—“clashes” rather than pluralism remains a standard trope across popular discourse. Referring to the “early success of multiculturalism in Britain,” and that nation’s attempt to “integrate, not separate” in a 2006 essay published by the Financial Times, Harvard University economist Amartya Sen lamented the abandonment of what he summarized as greater Europe’s “championing of every form of cultural inheritance.” Sen also warned: “The current focus on separatism is not a contribution to multicultural freedoms, but just the opposite.”

Fifteen years later, on the eve of Britain’s disorganized separation from the E.U., transmitting Europe’s complex, deeply interconnected multiracial heritage has never been more pressing. Because a small but growing cohort of scholars are already doing this work, there are several groundbreaking, positive, and multi-faceted studies from which to draw in pushing back against the spread of xenophobia. Moreover, despite a vague undercurrent of cynicism in the academy—e.g. political scientist John T. Scott’s review of historian Catherine Fletcher’s masterful study, The Black Prince of Florence: The Spectacular Life and Treacherous World of Alessandro de’ Medici—recovering and amplifying non-white voices, experiences, and representations in European Studies remains popular both in and well beyond the ivory tower.

Although Fletcher’s study—of the first black head of state in the modern Western World—does not make this connection, Alessandro de’ Medici’s African mother, Simonetta da Collevecchio, was likely named after Simonetta Vespucci (1453–1476), the Florentine model who was famously the muse of Giuliano de’ Medici. By the end of the fifteenth century, as the flourishing of black artistic representations of St. Maurice (like the two handsome images below), and an array of other cultural ephemera indicate, “whiteness” was far from the only standard of beauty in Europe on the eve of the so-called “High Renaissance” (1500–1530).

While the Renaissance was indeed more racially pluralist and sophisticated than is commonly assumed, the cosmopolitan habits and perspectives associated with this period were not new. In fact, both the medieval and early modern periods are especially powerful time periods through which to understand Europe’s heterogeneity—not least due to the continent’s burgeoning fascination with African wealth, characteristics, and civilization from the late thirteenth century onward. Centuries before the ascendance of scientifically-based racism that followed the onset of the Atlantic slave trade, blacks were welcomed, if not cherished, at royal courts throughout Europe. And as the story of Alessandro de’ Medici’s marriage to Margaret of Austria (1522–1586), the daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V affirms, “blackness” was clearly compatible with divine rule and princely virtue across greater Europe.

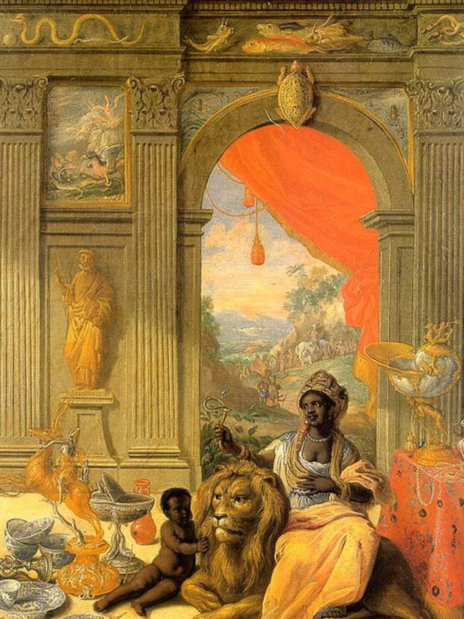

As Ivana Čapeta Rakić, Yona Pinson, and other scholars have pointed out, the Roman Catholic Church encouraged the positive incorporation of Africans and especially those who were Muslim—arguably the best evidence researchers have of uneven commitments to this ideal is iconography from the late medieval and early modern periods. Not only did a wide range of these artifacts mythologize the epic reach of the Catholic order, their promotions of a religious imaginary often stretched across three continents (e.g. the Biblical Magi, or Three Wise Men or Kings featured in the image below). However imperfect these gestures were, they symbolized the potential power of a global, egalitarian Catholic future, and a broader European interest in commemorating people of African descent that deserves more attention.

Given the tendency of scholars and commentators alike to emphasize the enslavement, oppression, and defeat of people of color by—“white”—Europeans, it is easy to see how Tarrant fell for the overwrought cliché of the totemic clash between the Ottoman Empire and Europe. We can safely assume that Tarrant remains completely unaware that the Dutch Republic—led by the highly-commercialized County of Zeeland, which New Zealand is named after—began trading directly with Asia in the seventeenth century to ensure its own religious freedom.

In addition to the internally displaced Dutch populations who escaped religious persecution by moving from the southern to northern Netherlands at the end of the sixteenth century, Jewish communities expelled from the Iberian Peninsula were also beneficiaries of this haven. And the sheer abundance of this nation’s striking late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century paintings of black Africans and other populations of color suggests that appreciating cultural pluralism was a standard rather than an exception in the early Dutch Republic.

Recalling these progressive intentions is not an apologia for the ineffable destruction Europeans caused in the early modern period. While Portugal’s seizure of major centers of the Asian spice trade between 1507 and 1515—most notably in the Malaysian city of Malacca, the Iranian island Hormuz, and the Indian city of “Old Goa”—was devastating, Dutch rule was even more brutal. And the commercial trade in black bodies beginning in the fifteenth century is a chilling reminder of why visual culture could never challenge large-scale human degradation.

Inspiring and downright horrific legacies of the first era of globalization should not be presented in zero-sum terms—especially given how interconnected civics, economics, politics, religion, and culture were in this period. More so than any other purpose, the brief reflections above suggesting a roadmap for “deprovincializing” early modern social and cultural history are driven by my own commitments not to echo a standard trope: that the history of Europe is synonymous with a history of “whiteness.” Not only has this tenacious, yet incorrect, understanding skewed the public’s intellectual development, it continues to support exclusionary social norms that neglect the histories, presence, representations, and experiences of non-white persons altogether.

Suggested Further Reading:

F. Earle, Black Africans in Renaissance Europe. Reissue edition (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Catherine Fletcher, The Black Prince of Florence: The Spectacular Life and Treacherous World of Alessandro de’ Medici (Oxford University Press, 2016).

David Northrup, Africa’s Discovery of Europe (Oxford University Press, 2013).

Revealing the African Presence in Renaissance Europe, Eds. Ben Vinson III, Joaneath Spicer, Natalie Zemon Davis, and Kate Lowe (Walters Art Gallery, 2012).