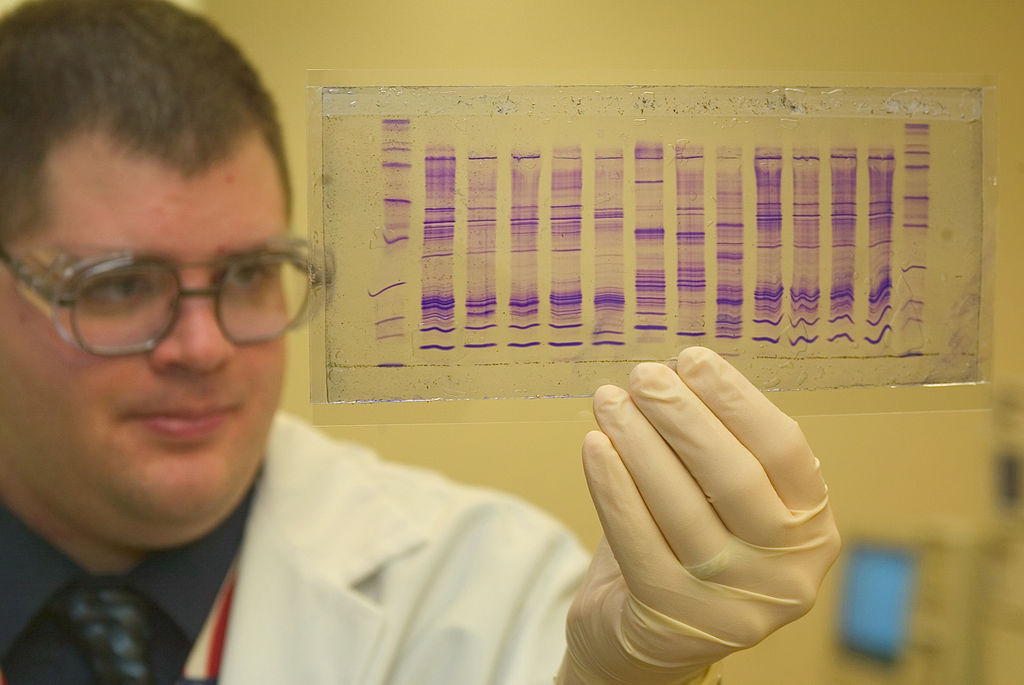

The scientific evidence suggests that the CRISPR technique is more precise than older, cruder techniques of genetic engineering.[1] Most scientific discussions about CRISPR are likely to lean towards medical applications, especially its seeming promise with respect to currently incurable human diseases and its use as a tool in the knowledge of human genetics. The broader public debate has narrowed its focus to application questions in human genetics alongside worries about the slippage towards human enhancement, and associated issues of justice concerning access. Many of the specific ethical questions that arise in advisory bodies are the same ones that are already all too familiar to those who have worked in the ethics of human genetics, namely those questions on safety, scope of usage, and means of achieving the end sought. That is, such bodies are most comfortable dealing with issues like safety, which amounts to a thin version of ethics that misses thicker ethical concerns.

What I want to offer here is not a claim to provide a possible consensus between such disparate groups, but rather a way of thinking which can help to rescue our ability to talk about more than safety and efficacy. This approach retrieves the virtue of practical wisdom, not least because I believe that it is relevant even more now that speculation about the possibility of accurate human gene editing is closer to becoming a reality.

Thomas Aquinas considered that there are small steps that ordinary people could take in order to acquire virtues, even those who did not necessarily have any particular religious faith. And crucial to those small steps is the exercise of practical wisdom. Practical wisdom is a source of insight and is a virtuous disposition that is particularly useful in the conduct of ordinary human affairs. As it is aimed at the common good, it can be applied in specific circumstances in different ways. Hence, a particular decision that follows the exercise of practical wisdom takes into account multiple factors in making that decision, even while keeping an open eye on whether that decision serves to achieve the goal of the common good.

While the moral virtues, such as justice and courage, on their own will incline their possessors towards right action, this inclination is not sufficient, which is why practical wisdom is so important. Practical wisdom helps to recognise those subtle differences that lead to a different course of action in given circumstances. Part of the challenge for CRISPR-Cas9, as with any other new and potentially influential technology, is that ethical decision making should not consider only the implications for one individual or family, but should also consider the wider socio-political implications. Truly moral decisions are not based on autonomy alone.

Practical wisdom, for Aquinas, has eight qualities, all of which are important in making a good decision. These qualities are: memory, teachableness, acumen, insight, reasoned judgement, foresight, circumspection, and caution. Memory (memoria) must be “true to being.” And it does not take long to realize that historical reflection forces a closer look at the long shadow of eugenics in the application of genetic science, a manipulation of human reproduction and discrimination against those with disabilities for ultimately political ends. Teachableness (docilitas), or open-mindedness, is a quality that many scientists will respect, since without open-mindedness discovery is much more difficult. But it is also a reminder that decisions are always embedded in complex networks of human needs and interests.

Acumen (solertia) includes the ability to act clearly and well in the face of the unexpected. Acumen makes it possible to act aright even when the time to make a decision is compressed. Insight and reasoned judgement, which are also in the list of intellectual virtues that practical wisdom requires, need to be brought to bear. Yes, some readers will now ask questions regarding, for example, whose insight and which reasoned judgements are assumed in such an account, but these questions do not undermine the effort to discern what should be done. What seems reasonable to one may not be to another, but in so far as prudential reasoning includes deliberation, it tries to take into account different reasonable points of view.

What additional elements need to be in place for practical wisdom to be possible? The first element here is foresight, which is the human corollary of divine providence, since divine providence always aims at the ultimate good, while foresight seeks to imitate that orientation. Foresight is the ability to know if certain actions will lead to a desired goal. The judgements of practical wisdom are not fixed or certain in ways that might be the case if it were simply an application of rules or principles. This component is crucial for judgments about CRISPR-Cas9, especially in view of the fact that many of the so-called predictive beneficial effects have not come to pass in genetic medicine. Is this newest and what looks like the most promising technology an exception to that trend, or is this yet another example of over-enthusiasm in the wake of a new and exciting discovery? Are the uncertainties sufficiently strong to be tolerated or not? And who will be the major beneficiaries?

Aquinas also includes circumspection and caution in the list of the components of practical wisdom. Circumspection is the ability to understand the nature of events as they are now, while foresight is the ability to understand events as they might be in the future. The difficulties with CRISPR-Cas9 are that it is very hard for a non-specialist to fully understand what is, in fact, certain knowledge and what is less so. Caution has to do with imprudent acts that are too hasty, and avoiding obstacles that might get in the way of sound judgements, though caution that leads to inaction is not really what Aquinas had in mind either. In this sense, freezing all action due to an over-inflated sense of caution may not be appropriate, but caution has to keep in mind the overall trajectory of scientific research in this field. Caution here refers not just to safety issues, but wider more substantial questions about the kind of human community that is envisaged—in other words, what human flourishing actually means. In addition, Aquinas also recognises the place of gnome, that is, the wit to judge when departure from principles is called for in given situations.

Practical wisdom as setting the mean of the moral virtues is concerned with individual prudential decisions. But practical wisdom reaches beyond this in order to inform political governance. While Aquinas’s discussion of practical wisdom bears some relationship to that in Aristotle, in this respect it is different, for Aristotle confined his attention to individuals. The common good is that which is related to the good of all and the good of each, and in Aquinas’s time it meant the state. While the rule of nation-states are more complicated now with international laws, and the power of transnational companies exceeds that of some states, the overall intention of political practical wisdom towards the common good still applies.

Part of the contestation of CRISPR is related to questions about what that good means, and for whom. In other words, what does it mean for a human community to flourish? Aquinas is also more communitarian compared with the individualism that prevails in the current climate, so when individual practical wisdom clashes with economic or state practical wisdom, the former has to give way to the latter. Distributive justice and political practical wisdom work together for the same end though they can be distinguished in their role. It may be that the rhetoric of the “common good” was once used to promote eugenic practices. But in the current context of deliberations over the use of CRISPR technologies, using such technologies to promote racial purity by a powerful elite for their own particular ends would be necessarily excluded. Hence, rather than opposing eugenic practices by avoiding any collective sense of what the good might require and resorting to individual autonomy as the way forward, a more promising approach is to insist on a greater scrutiny of what social, political, and collective goods require using the tools of distributive justice and political practical wisdom.

Just as individual practical wisdom sets the mean for the moral virtues, so political practical wisdom sets the mean for distributive justice. Distributive justice is concerned with the relationship between the community and individuals, but what this distributive justice might require is not self-evident in all cases, and needs to be supplemented by political practical wisdom in much the same way as correct decision making for the moral virtues must be supplemented by individual practical wisdom.

Political practical wisdom is one way of helping to heal the rift between public and private morality, and the false divide between a “subjective” virtue ethic that is concerned with individuals and principled “objective” approaches that are more often concerned with wider social contexts. This is particularly significant in adjudicating heated public contestations regarding CRISPR technologies, since much of the discussion seems, like many other controversial issues, to rest on key exemplars which provide the basis for lobbyists either in favor or against this technology. Take, for example, the case made by Erika Check-Hayden based on the example of Ruthie Weiss, who has albinism and who has appeared in media reporting on CRISPR. Check-Hayden reports that when you ask patients like Ruthie, or her parents, if they would they have used CRISPR to prevent albinism, the answer is a resounding No. Why? Because what makes Ruthie Ruthie is the challenge she has faced and the particular determination to live in spite of these disadvantages.

Poignant though this story is about the virtue of perseverance in the face of hardship, I am less convinced by arguments of this type. This is because the arguments rest on a particular subjective experience of an individual who suffers from a particular disability. Was it prudential for the parents to indicate that Ruthie should not have been engineered? Of course, simply from the parental perspective, given that Ruthie’s life was viewed as positive, they would not have wanted Ruthie to be anything other than who she is. Their memory of the positive aspects of her life informed judgments about what was right to do. But what if both Ruthie and her parents had suffered inordinately from her condition and could imagine doing virtually anything to change it? In that case, the option of CRISPR could well have seemed prudential to those parents. The point is that prudence takes into account not just our subjective feelings and experiences but wider societal constraints, circumspection includes knowing all the details from many different perspectives, so familial anecdotes are insufficient to make public policy. Further, assuming, as the parents did, that Ruthie would have been changed for the worse, does not really understand the nature of genetic engineering. Ruthie would have been a very different child if engineering had been permitted, so it would be virtually impossible to project back into the past and ask if some of her unique characteristics could thereby be compromised. The voices of those who have been excluded from discussion certainly need to be taken into account, but as a way of informing wider discussion rather than resting on a few emotively charged media-driven examples.

Practical wisdom applies to different levels; the level of the individual, yes, but also at the level of the family, the community, and the state or system of governance. Such an approach which stresses a movement away from isolating the individual towards complex multivalent levels in envisaging the good applies whether or not a specific Christian and Thomistic understanding of that good is sought. To be clear: individual goods in the approach I am arguing for are not denied, but such goods are sought within a much broader context of what that good might mean as embedded in specific social contexts operating at different levels. Bigger questions that relate to that part of practical wisdom called foresight include taking account of broader consequences, such as whether the technology is desirable at all for the common good; thus, who is really going to benefit from the use of the technology, what implications are relevant for a given community, what impact such applications might have on the use of resources, and so on are just as important. Which population groups will be used in clinical trials that will inevitably be set up to test efficacy, such as gene technologies that work to “correct” AIDS or other immune deficiency diseases such as Severe Combined Immune Deficiency (SCID)? Single gene diseases such as Tay Sachs may seem obvious as a first step in the application of CRISPR-Cas9, and may even be preferable for conservatives since the manipulation will be on sex cells rather than the embryo, but a prudential decision in a given community will also place such seeming advantages in a wider social and political context. Practical wisdom also helps to judge what the virtue of justice requires in given circumstances in so far as it is orientated towards the common good. It seems highly likely that the most vulnerable will be the target of any such campaign for trials in the lead-up to large-scale application in therapeutic treatments. Are all such treatments necessarily desirable as ends to promote overall human flourishing or not? However, in the Thomistic tradition practical wisdom provides the means, at least, to attempt to take account of a multiplicity of factors in decision making, including what such “balance” might look like in practice; for example, by giving moral priority to the weak, but not just those who are suffering various diseases.

Practical wisdom is not a panacea, but it may be an important alternative to the idea that all we need to do is apply fixed principles such as individual autonomy to ethical problems that are, at root, the same. A broad framework for decision making through a prudential lens acts as a guide that is less about absolute rules of right or wrong and instead concerns taking appropriate responsibility for human flourishing as perceived according to specific virtues of the human community, namely those virtues of practical wisdom, charity, compassion, and mercy.

[1] This blog draws on ideas that are further developed in the following: Celia Deane-Drummond, “The CRISPR Challenge and the Beatific Vision: Recovering Practical Wisdom as a Guide for Human Flourishing,” in Eric Parens and Josephine Johnson, eds., Human Flourishing in an Age of Gene Editing (Oxford University Press, 2019).