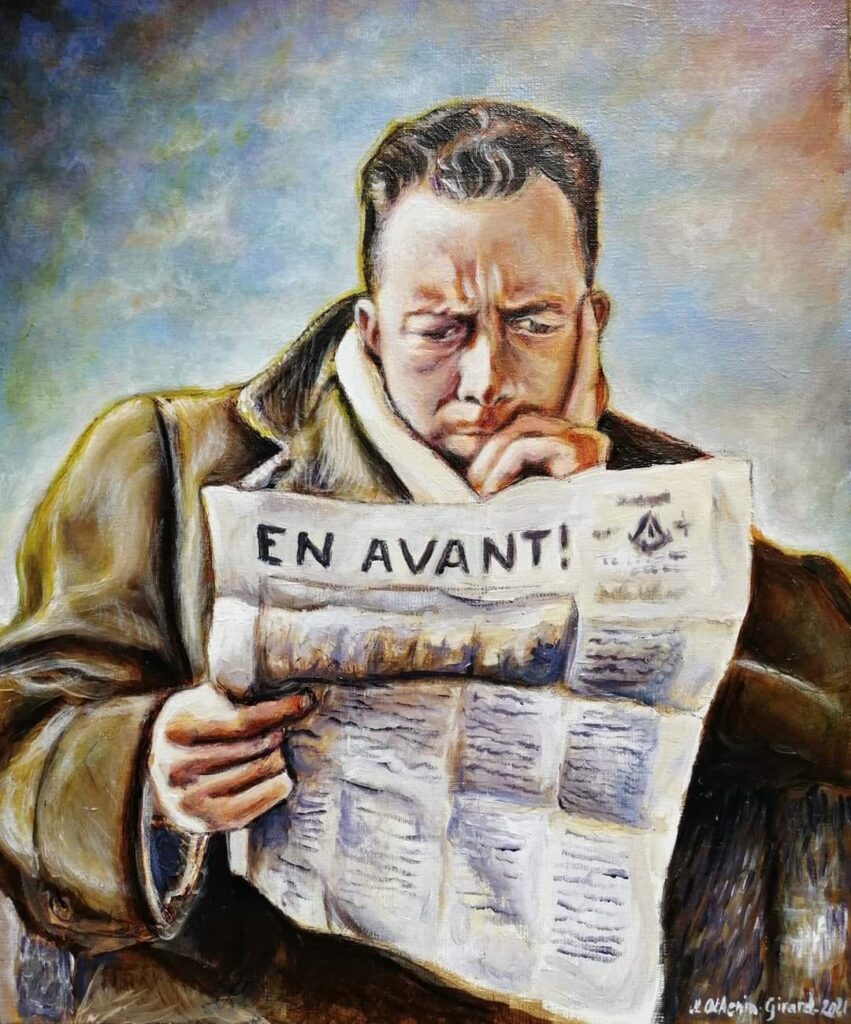

In the 1947 novel The Plague, his great allegory of the struggle against fascism during the Second World War, French Algerian Nobel laureate Albert Camus wrote, “Everybody knows that pestilences have a way of recurring in the world; yet somehow we find it hard to believe in ones that crash down on our heads from a blue sky” (35). As the razing of Gaza continues, we can learn from thinkers like Camus who confronted the realities of terror in his time with resolute commitment to human equality.

Camus’s context was French rule in Algeria, a North African colony and later part of France until its 1962 independence. Conflict erupted between the pieds-noirs, French Algerian citizens of European descent, and Indigenous Arab and Berber populations who, despite their overwhelming majority, were denied political and civil rights. Despite being a colon, or “settler,” Camus’s lifelong anti-colonialist activism confronted systemic injustice and sought a “fair Algeria, where both peoples can and must live in peace and equality.” He stood athwart an Arab nationalist insurgency that targeted and killed many civilians, led by the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN), and state counterterror and settler vigilantism. Amid death threats, Camus insisted that nothing strips human beings of their right not to be murdered.

The Camusian argument to follow is that the wrongness of murder is obvious, straightforward, and sets a normative limit on how one may wage or justify resistance to violence or oppression; and that ignoring this is wrong, not least because it hinders shared recognition of responsibility for harms and blocks solidarity in seeking peace with truth and justice.

Against Executioners

The term “executioner” fills Camus’s writings, reflecting his passionate opposition to capital punishment. His revulsion at what he called “the most premeditated of murders” can be felt in his 1942 novel The Stranger, published in Nazi-occupied Paris where he lived and secretly worked as a journalist and editor-in-chief of Combat, a banned Resistance newsmagazine. And it’s central to The Plague, where Tarrou, Camus’s mouthpiece in the fable of resistance against occupation and oppression, declares, “All I maintain is that on this earth there are pestilences and there are victims, and it’s up to us, so far as possible, not to join forces with the pestilences” (236).

I believe that standing against executioners is twofold: we must identify, and avoid identifying with, those who commit or excuse murder. Moreover, we have a special responsibility for wrongful acts we help others do.

We clearly help others harm by materially supporting their efforts. But we also help the harmful when they credibly act in our name or by our authority. If I am in a power-sharing relationship with another, their acts bear my imprint, marking my character. In a way, we act together, which is the basic meaning of “complicity.”

These are plain facts about sharing moral responsibility for what others do. Their truth rests on common sense and experience, not fancy theories. They mean my personal involvement in a crisis has the greatest relevance to what I should say or do about it. Grand narratives and intellectual frameworks deserve a subordinate, defeasible role.

Discourse about Israel/Palestine revolves around concepts like “Zionism,” “apartheid,” and “a nation’s right to exist.” These evoke important realities. In The Plague, Camus has the redoubtable Dr. Rieux, who distrusts sweeping ideals, admit that “when the abstraction is trying to kill you, you have to pay attention to it” (93). But abstractions cannot simply dictate how I should respond to crisis. I must know who I am in relation to it, whether harm is done with my help or in my name.

Against Abstraction

In The Rebel, Camus confronts the tendency to prioritize abstractions over lives. Devotees of stories about historical purity or theories of utopian progress readily find reasons for eliminating real people who appear as obstacles. Venerating ideas risks devaluing individuals. Such “redemptive politics” wears many guises: capitalist imperialism, totalitarian communism, colonialist domination, revolutionary terror. No monopoly exists on this perverse idolatry of the ideal.

Even an indispensable idea like antisemitism can be abused and corrupted. Many on the political right use the concept to shield Israel from its critics, many of whom are Jewish. If political Zionism was inherent to Jewishness, all Jews would share responsibility for its mistakes.

Yet the charge of antisemitism is weaponized by populist demagogues like Ron DeSantis, who brands “all” Palestinians genocidal antisemites to justify denying refugee status to displaced families. This is as dehumanizing a slur against them as it is insulting to Jews suffering from the grim realities of antisemitism.

Redemptive politics also inspires moral perversions on the far left, as recently illustrated by victim-blaming statements issued by progressive organizations like the Democratic Socialists of America. Ethically, nothing makes anyone more murderable. Yet blaming terror on its victims is a longstanding moral blind spot on the left. Camus’s contemporaries John-Paul Sartre and Frantz Fanon theorized that the source of all violence in anticolonial struggles are colonial systems and settler populations, which are therefore “entirely responsible” for it. Some on today’s left inherit these ideas, twisted fictions of agency that reduce human beings to conduits of abstractly described structural forces. This is how an otherwise normal person comes to believe that a grand historical process or myriad institutions, not an angry man aiming a loaded gun at a child he views as a colonizer, is responsible for pulling the trigger.

None of this entails a broad equivalence between far-right demagogues who weaponize antisemitic accusations to justify Israeli atrocities and far-left actors who blame October 7 on its victims. The Camusian lesson is rather that ideology must not be used to justify atrocity any more than to block legitimate resistance to oppression.

“Humanity Isn’t an Idea”

Standing against executioners while keeping abstraction in its place means recognizing our relations to the realities of murder. Two points help: all civilian life matters equally and we are responsible for the destruction of life to which we contribute.

The first point precludes supporting, excusing, or dismissing either the vile atrocities of Hamas on October 7 or those aspects of the Israeli military response described by the U.N. Secretary-General and other experts as involving war crimes and by the International Court of Justice as plausibly genocide. For American taxpayers, the second point means that because Israel receives nearly $4 billion annually from authorities that tax and represent us, our role is morally asymmetrical. We rightly criticize Israel whose operations violate legal conditions on our military aid.

These operations have killed over 33,000 Palestinians, of whom three-quarters are women, children, and elderly. The U.N. Secretary General describes Gaza, one of the most densely populated regions in the world, as a “graveyard for children.” At half of Gaza’s population, children constitute over 13,000 of those so far killed by Israel. This amounts to roughly twelve times as many children slain by Israeli forces as all Israelis killed on October 7. A human-centered ethic means nothing if not solidarity with every child.

This carnage constitutes unjustified killing for two reasons.

First, the laws of war protect civilians both from deliberate targeting and from being killed in numbers disproportionate to legitimate military objectives. The law defines “excess” harm in terms of “clear and direct” expected advantages. Those resulting from Israel’s operations evidently are neither.

Second, many of Israel’s actions are unlawful, proportionality notwithstanding. Its Gaza siege escalates a 16-year blockade and occupation that human rights experts deem a form of illegal collective punishment. The siege’s costs include over one million people poisoned and chronically deprived of medical care. Of 2.2 million Gazans, 85% are displaced and 25% are starving. 31% of children under 2 are acutely malnourished.

Anyone like me, in whose name an ideology or identity is used to justify carnage, must “venture into a no-man’s-land between hostile armies.” The Plague’s Dr. Rieux addresses us too when he reminds his colleague, Rambert, who lapses into abstraction amid crisis, that “Humanity isn’t an idea” (175).

For “A Civilian Truce”

On January 22, 1956, Camus delivered a violently protested speech in Algiers. In a desperate plea to pieds-noirs and Arab nationalists, he begged both to refrain from murder. The foremost reason was “one of simple humanity,” that “no cause justifies the death of the innocent.” He later dispatched over 150 letters to French authorities urging mercy for Arab militants facing execution or imprisonment, some of whom Camus believed had committed atrocities. Some letters spared lives. But Camus’s antiracist appeal for a civilian truce failed. His public voice lapsed into “Sophoclean silence.”

My Sisyphean appeal joins many others’. Jewish Voice for Peace’s declaration, “Not in our name!”, acknowledges a heightened obligation to oppose murder when one’s authority is used to justify it—even illegitimately or indirectly. This is the tragic side of responsibility. When others speak or act on my behalf, they pose, and would answer, the question of who I should be taken to be. They put a choice before me: to define myself or let them do it for me.

Camus understood that withdrawal from a violent world may tempt us but isn’t possible. The effort makes us bystanders, if not strangers, to ourselves. “By our silence or by the stand we take,” he reminds us, “we too shall enter the fray.”