Narendra Modi’s recent inauguration of the Ram temple in Ayodhya not only celebrated the culmination of a Hindu nationalist dream; it also marked a crucial moment in reimagining India as a “civilization state” instead of as a republic. The term “civilization” was splashed across media reports quoting the reactions of senior leaders in the ruling Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP) to the event. The external affairs minister S. Jaishankar remarked “the soul of a civilization finds expression once again.” The chief minister of the state of Goa declared this to be a “moment of civilizational resurgence, civilizational renaissance in the country.” Media figures quickly mirrored this framing and a number of television commentators reiterated that this was “a civilizational moment.” The normalization of this terminology belies its deep implications for the state that Hindu nationalists wish to create.

The current vision of India as a “civilization state” has found widespread expression since Modi’s election in 2014.[1] This development reflects the growing tide of authoritarianism worldwide as well as the internationalization of far-right political movements. The claim of being a “civilization state” is not unique to India—many in China, Russia, and Turkey also invoke a similar rhetoric. Indeed, the discourses and practices of aspiring civilization states have much in common. Their proponents imagine the state to be the embodiment and fulfilment of an abiding civilization. This idea of the civilization state opposes liberal democracy’s claim to universality, a universality that is perceived to be western rather than truly for all.

But the term civilization itself is a neologism that emerged in mid-eighteenth-century France. It was deployed during the period of European colonialism and thereafter, often to underscore European superiority and to further the modernizing projects of colonial rule. Today, however, these new visions of the civilization state embrace a nativism that rejects Euro-American hegemony, combined with a notion, stemming from nineteenth-century European thought, of the nation’s spirit or soul finally unshackling itself to achieve its destiny. In today’s India, a sizeable cohort of right-wing intellectuals promotes such a civilizational vision. They are supported by a media that is pliant before the government and its oligarch allies. As Rodrigo Nunes points out, such “political entrepreneurs” now constitute an influential organizational form for the right-wing, not just in India but elsewhere, including the United States and Brazil.

Hindu nationalists are not the first in India to link the modern nation to the idea of an ancient civilization. However, unlike secular nationalists, such as India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, they infuse this notion of Indian civilization with a markedly Hindu character. Often adopting a decolonial rhetoric, they portray past Muslim rulers as colonial oppressors. In this view, for India to flourish, she must avenge a host of historical wrongs perpetrated centuries ago by Muslim kings. For example, when in 2019 a Supreme Court verdict allocated the site of the former Babri mosque for a Hindu temple, Jaishankar exultantly declared this “a pledge redeemed, a heritage reaffirmed.” This obsession with the past functions as a metonym for the Hindu nationalist goal of dominion over India’s roughly two hundred million Muslims. Politicians regularly engage in rhetorical dog whistles that frame Indian Muslims as co-extensive with the historical rulers who are now targets of hatred. On a daily basis, Muslims in India also face routine discrimination and disproportionate violence.

Unlike secular nationalists, such as India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Hindu nationalists infuse this notion of Indian civilization with a markedly Hindu character. Often adopting a decolonial rhetoric, they portray past Muslim rulers as colonial oppressors.

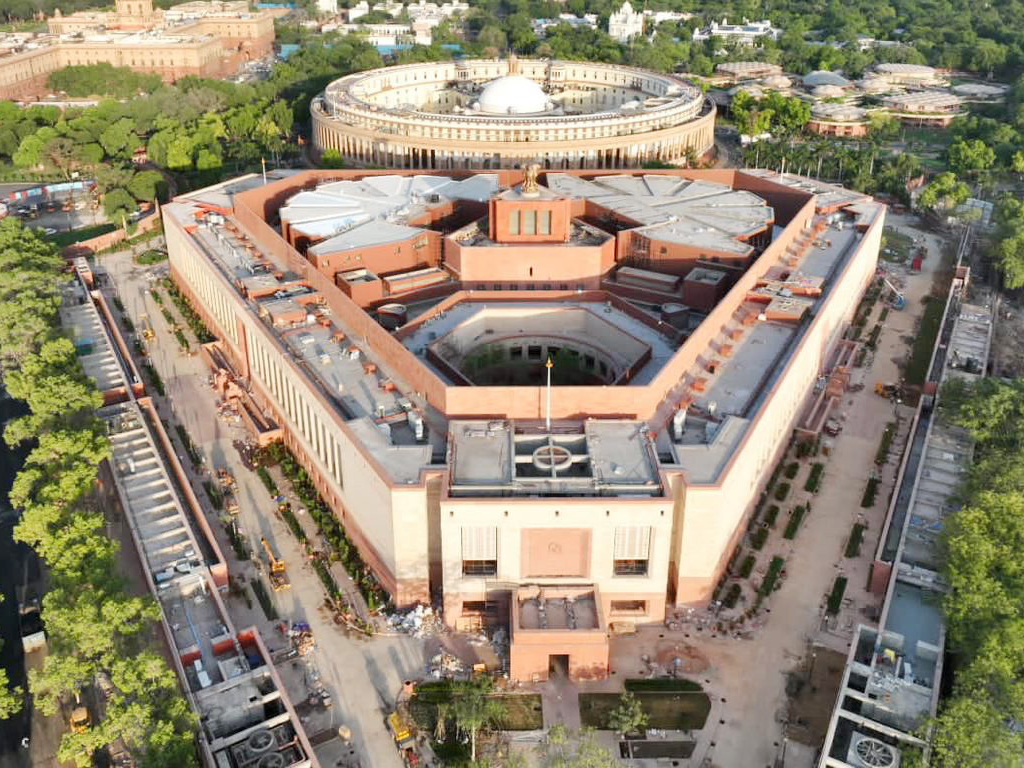

Civilization states do not exist in and of themselves; they must be built—through force, erasure, rhetoric, grand spectacle, and, in this case, bulldozers together with plenty of concrete and stone. By the time Modi inaugurated the Ayodhya temple, he had overseen several other giant infrastructure projects across the country. These include a mammoth restructuring of central Delhi already underway, with a new parliament building and a prime minister’s mansion planned with room for several hundred staff, abundant watchtowers, and a secret tunnel. Another project in Varanasi razed old residences and stores in a dense neighborhood to create a huge path and complex around the Kashi Vishwanath temple. Activists now seek to demolish a seventeenth-century mosque abutting the temple; a court has already handed it over for Hindu worship. Meanwhile, untold numbers of Sufi shrines, some hundreds of years old, are being demolished on the grounds that they are illegal encroachments, or that they come in the way of necessary infrastructure development.

In this civilizational project, the reconfiguration of time, past, present, and future, accompanies this restructuring and resacralization of space. A common element binding these temporalities is the presence of a sacred king or king-like figure. As regards the past, a pamphlet prepared for the G-20 summit of world leaders in Delhi held in 2023 illustrates this kind of Hindu nationalist historical narrative. It traces the genesis of democracy in India to the Vedas, as, apparently, these ancient texts contain words that could mean a council or an assembly. However, kingship rather than participatory governance has pride of place in this account. Several examples present idealized images of Hindu kings who were beloved by their people and took counsel from their ministers. According to the view offered here, these rulers were thus presumably progenitors of the modern democratic state. This vision extends to current times. As far as the present and future are concerned, it is Modi, as a redemptive philosopher-king, who will usher the nation into a new and better age. For example, Modi reimagines a dominant Sanskritic conception of time according to which the present era is called Kaliyuga, or the “age of darkness,” by declaring that under him India has now inaugurated the era of Amritkaal, or the “epoch of ambrosia.”

The idea of the Indian civilization state benefits from its conceptual fuzziness. Its markers are embedded in an assemblage of myriad aesthetic forms and practices such as yoga and lacto-vegetarianism that are not always obviously or exclusively linked with Hindu nationalism. According to its proponents, civilizations are not religions; that is to say, they are wider and more encompassing up to a point. For instance, a senior intelligence and national security official in the current administration frequently declares India to be a civilization state, whose basis is not language, religion, or ethnicity but civilization itself, which forms the nation’s “collective unique common consciousness.” It is striking that here he also invokes Israel as a similar case of a civilization state.

Nonetheless, this notion of the civilization state is infused with a worldview of Hindu supremacy, which pervades its various and sometimes contradictory articulations. On the one hand, this civilizational rhetoric resonates with the widespread idea that Hinduism is no mere religion, but rather the foundational matrix of Indian civilization. It is for this reason that Vinayak Savarkar, premier ideologue of Hindu nationalism, distinguished Hindutva, or Hindu-ness, from Hinduism as a religion. Hindus do not agree on the essence of Hinduism, observes Savarkar. By contrast, for him, Hindu-ness, defined by claiming the nation as both holy land and fatherland, unites all Hindus with Buddhists, Jains, and Sikhs, and excludes Muslims and other members of the Abrahamic religions. On the other hand, when expedient, this rhetoric also embraces the colonial idea of Hinduism as a world religion. Thus, Hindu nationalist supporters unironically compare the new Ram temple in Ayodhya to the Vatican or to Mecca. The implication here is that India is the seat of Hinduism, which ought to be regarded as the only authentic religion of the Indian people.

This civilizational rhetoric resonates with the widespread idea that Hinduism is no mere religion, but rather the foundational matrix of Indian civilization.

Political opposition to the ruling BJP has at times invoked the Constitution of India as a uniting symbol. The Preamble to the constitution, adopted by India’s Constituent Assembly in 1949, calls for securing justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity as the goal of this newly independent republic. While this idea of a republic is still ensconced within the limiting framework of the nation state, it is based on universalistic and forward-looking principles that are at odds with the Hindutva civilizational imaginary. Just like the republic, however, the civilization state is an unfinished project; a project that can potentially be resisted, interrupted, diverted, or remade. It is the opposition’s task to determine how to do so—a challenge made all the more difficult by the ongoing onslaught of political repression.

[1] The concept of the Indian civilization state has recently begun to garner critical scholarly attention. See, for example, a special section devoted to the subject in the March 2023 issue of International Affairs.