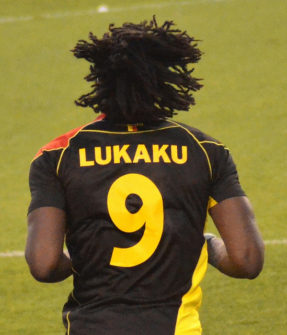

A video circulating on Facebook shows a crowd of men standing in front of a cafe cheering and dancing to the rhythms of a darbouka, a Moroccan tambourine. The video was shot in Molenbeek, one of Brussel’s nineteen communes, which recently gained international notoriety due to the implication of a few of its residents in international terrorism. Yet in this context, the commune was the setting for a more joyful event. A crowd of men of Maghrebi origin danced and sang while waving the Belgian flag as cars drove along, honking to the rhythms of the dancers. The crowd was celebrating Belgium’s advance to the semi-finals of the FIFA World Cup—a historic event for the country, which had only reached that stage one time earlier when the team around the legendary Jean-Marie Pfaff managed to make it to the semi-finals of the World Cup in Mexico in 1986. But there are important differences between the team that qualified in 1986 and this one, differences which also explain why large parts of Molenbeek were celebrating this historical achievement. With the presence of Belgian-Moroccan star players Marouane Fellaini and Nacer Chadli, in addition to two players of Congolese descent, Romelo Lukaku and Michy Batshuayi, the composition reflected the highly diverse demographic realities of the Belgian metropoles. Furthermore, this victory comes at a moment when intense tensions about migration run through the country, providing a welcome counter-narrative to the doom and gloom scenario that prevails in the rhetoric of the leading nationalist political elites.

Analysts have often held ambivalent views on the potential that soccer, and sports in general, have in overturning existing power imbalances and racial hierarchies within societies. The overrepresentation of ethnic-cultural minorities in various sports is not a novelty. Like other professional circuits, such as music, sports have traditionally been one of the spheres through which racialized minorities could progress and gain a degree of fame, wealth, and social mobility. One of the reasons often advanced to explain this overrepresentation of minorities in sports is the way in which it comfortably confirms, rather than disturbs, racial hierarchies and stereotypes: Black or Arab men are primarily seen as productive bodies, with entertainment value. This is also why many have warned against mistakenly seeing a diverse national football team as a sign of tolerance or inclusion. The victory of France in the 1998 World Cup, with a team coined “Black, Blanc, Beur” [beur meaning Arab in slang], did not stop the political advance of the National Front a few years later, nor did it stand in the way of rampant anti-Muslim rhetoric and strong secularist measures targeting veiled women that continue to this day. Furthermore, figures like Zinédine Zidane were even hailed as examples by some commentators of the success of the French model of laïcité and assimilation. Born to an immigrant father from Algeria, Zidane does not display an explicit identification with Islam. Another danger looms in the uncritical celebration of football as a carrier of diversity, in that players of foreign descent are only hailed when they are heroes, but are immediately castigated when they fail. The same football star, Zidane, who achieved a quasi-divine status in football and was celebrated as a model of integration, went overnight from hero to savage (Arab) during the historic confrontation with Italian player Materazzi in the World Cup final of 2006.1

There are, however, reasons to also consider another side of this story, particularly when it comes to the Belgian national team and the celebration of it. Due to its fragmented political and social history, Belgium never successfully managed to tell a coherent national story about itself. And it is precisely this absence of a unified national project that allows for a triumphant recuperation of national symbols by ethnic minorities and expressions of difference that are otherwise marginalised.

Since its establishment in 1830, in the aftermath of the defeat of the Napoleonic empire and as a result of a mobilisation of a Catholic and Francophone elite who were unhappy to live under the tutelage of a Protestant Dutch monarch, the small kingdom of Belgium, with its 11 million inhabitants, has been beset by a never-ending succession of tensions around language, religion (Catholic/secular), and economy—with postcolonial migration being the newest addition to the historical fault lines identified by the Belgian sociologist Luk Huyse. Most of these migrants are descendants of workers who came to the country after the Second World War from Italy, Spain, Morocco, or Turkey. The nineties saw another wave of immigrants, mostly political refugees from Belgium’s former colonies in Africa’s Great Lakes region (Congo, Burundi, and Rwanda). The result is a highly diverse reality where metropoles like Brussels, which are home to players like Fellaini, Lukaku, or Batshuayi, have become minority majority cities where Arabic eclipses Dutch as the most used language after French. This multicultural composition of the country sits uncomfortably, however, with the prevailing models of inclusion which, in contradistinction to France or the UK and the US, are not unified into a single national model. In Flanders, a region where separatist and nationalist parties represent more than one-third of the electorate, an ideology of linguistic and cultural purism prevails. The Francophone part of the country is, in turn, highly influenced by the French model and puts more emphasis on secularism, although its various attempts to inscribe laïcité in the national constitution have so far failed.

Yet, and to the dismay of many, the players of the national team do not neatly abide by any of these scripts—just like many of the postcolonial minorities in the country who are currently challenging Belgium’s colonial legacy and white imaginary. On the evening that Belgium managed to secure a position in the quarterfinals, after an impressive come-back against Japan, Michy Batshuayi circulated a video recorded in the dressing room where he congratulated, in French with some Moroccan terms, the ‘draries’ for the victory, emphasizing the sentiment with expressions of ‘wallah’ [I swear in the name of Allah] and ‘shukran’ [thank you]. The word ‘drari’ [literally: boys] is a Moroccan word used in vernacular language to designate street kids, and has turned into a popular concept within youth culture, just like ‘wallah.’ Referring to the exploits of his teammates Chadli and Fellaini who were vital to Belgium’s win, Batshuayi’s performance reflects the importance of these ethnic and religious markers and the many linguistic crossovers found in youth culture across the ethnically diverse Belgian metropoles. Belgian flags, with the green star of the Moroccan flag added to the Belgian tricolour, circulated as a joke, as did the hashtag #valeurajoutée (added value): a response to the controversial Federal State-Secretary of Migration and Asylum Theo Francken, who openly wondered in 2011 what the added value of Moroccan or Congolese migrants was for the country. A similar event occurred after Belgium qualified for the semi-finals last Friday: Liège-born Nacer Chadli thanked his fans on his Facebook account, concluding with the words, “Allah is the greatest.” In a context where such a formulation, and in particular its Arabic variant (Allah-u Akbar), has become linked with violent extremism, and where public expressions of religion are met with suspicion, this public declaration of faith probably raised more than one eyebrow. And in a recent interview with The Players’ Tribune, star striker Romelu Lukaku opened up about his experiences of racism in Belgium, declaring that he would be surprised to find a single black person who hasn’t faced racism in the country, and challenging the general climate of suspicion that exists towards minorities and migrants in his birth country.

The so-called ‘golden generation’ of Belgian players is exceptional in several ways. Not only does it excel in technical skills and team play, but more importantly in the way it echoes many of the cultural and political developments within the country, not the least of which is the growing outspokenness of the descendants of postcolonial migrants who, by sharing their experiences of racism and openly challenging some of the prevailing colonial narratives, seek to carve out a space of their own. This also partially explains the immense enthusiasm and overwhelming support they elicit throughout the country. Each of the players seems, in his own way, to shed light on different compositions of Belgium, some of which does not conform to the more dominant nationalist or highly secularist narratives in the country.

A few weeks after the 22 March 2016 attacks in Brussels, the Federal Interior Minister Jan Jambon declared in an interview with the Belgian daily De Standaard that “a significant part of the Muslim community was dancing in the streets after the attacks.” His words prompted many angry reactions in the press with people denouncing these statements as an instance of fake news and demanding evidence for these claims while accusing the interior minister of polarising the country at such a sensitive moment. While the Interior Minister failed to substantiate his claims and never apologised for his statements, the expression “Muslims are dancing in the streets” has turned into a parody to mock the Interior Minister. So too with the dancing Molenbeekois who, through their dances and songs, were seen by many as reclaiming this victory as also theirs.

[1]This point is analysed further by Paul Silverstein (2018) in his recently published Postcolonial France. Race, Islam, and the Future of the Republic, London: Pluto Press.