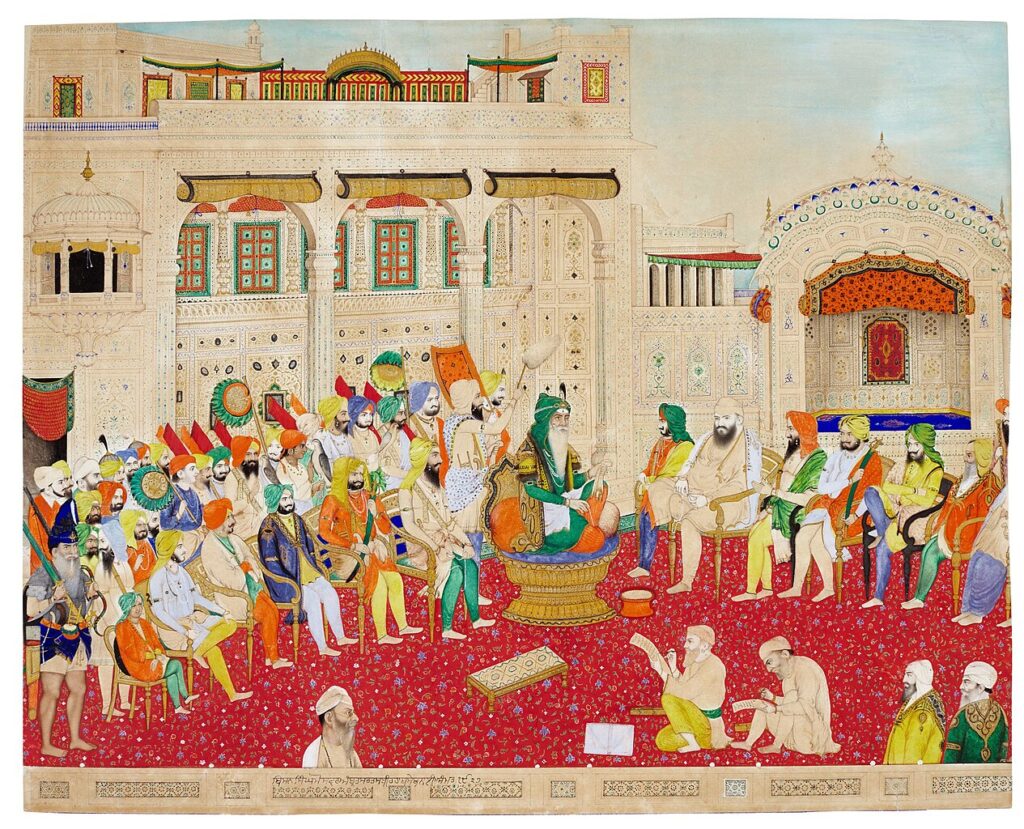

In Prophetic Maharaja, Rajbir Singh Judge has written a stunningly eloquent and conceptually deep account of the late-nineteenth century events surrounding Duleep Singh. Singh was the heir to the Sikh kingdom of Ranjit Singh, which was the last major British conquest in South Asia, on the road to India becoming the “jewel in the crown” of that most recent and most global of empires. In the eighteenth century, the Sikhs—more precisely, the Khalsa Sikhs—went from being targets of erasure at the hands of the imperial predecessors of the British to rulers of an area larger than Great Britain. The loss of that kingdom has continued to have a powerful hold on the Sikh imagination into the twenty-first century, and it plays a central role in Judge’s book.

Judge focuses on the relatively immediate aftermath of the fall of the Khalsa kingdom, noting that the “aftermath continues into the present” (11). In this piece, I will offer some thoughts on this aftermath, and how and why it continues into the present. This arc of history includes the independence of India from the British, its partition and the violent displacement of Sikhs, along with Hindus and Muslims, the struggle of Sikhs for security and recognition in the nation-state of India, and a new cycle of violence that has cast a shadow—now become global—over the present. If ethics and justice matter—and they are arguably at the heart of the teachings of the Sikh tradition—then delineating a path that, if actively followed, moves humans toward more ethical and just conditions for all, is worthwhile. Understanding the arc of this particular slice of history may be at least somewhat relevant for defining this path.

Engaging with Loss

Loss is a crucial conceptual driver of Judge’s account of Duleep Singh and his later-life struggles, long after he had been deposed and exiled to Britain as a boy and brought up as a Christian gentleman there, almost as a kind of imperial mascot. As Judge himself states, his goal is to “highlight how a people articulated loss (military, political, and psychological). Through theological debate, literary production, bodily discipline, and the cultivation of ethical practice, Sikhs undid the colonial politics that sought to conquer, secure and map the world.” Further, “Sikhs … were not seeking to recover the past. They engaged loss by remaking it [the past]” (2).

The loss of the Sikh Kingdom has continued to have a powerful hold on the Sikh imagination into the twenty-first century, and it plays a central role in Judge’s book.

At the same time, Judge does not offer neat explanations of the past, nor of attempts to remake the past. Drawing on Gil Anidjar, he cautions that there is no lesson to be learned for the present or future, at least at that level, from history. Instead, quoting Stefania Pandolfo, Judge considers “invention at a time of political and cultural crisis” and “the possibility of transmission for a tradition uprooted from its system of reference” (9; in Judge, 11) after the fall of the Khalsa Raj (sovereign rule) and the exercise of British imperial power across all aspects of South Asian societies and cultures. His book is meant to “participate in such uprooted transmission” and grapple with a “fractured inheritance and system of reference” for the case of the Sikhs at this juncture of the past (11).

As noted, Judge focuses on the near aftermath of the fall of the Khalsa Raj, noting in passing that the “aftermath continues into the present.” In the remainder of this essay, I will consider this aftermath, and its continuation into the present. In doing so, I will refer to Judge’s work at various points, although my own inclinations as an empirical social scientist are to look for lessons in the past, or in general, in the data. So, I will not achieve his level of methodological sophistication, although I admire it greatly. Instead, there will be a historical arc, and possible lessons, in my discussion.

Framing the Sikh Tradition

Despite recent attempts to define a medieval “Sant” tradition, and squeeze Nanak—the first Sikh Guru, or spiritual guide—into that relatively modern category, Nanak and—for the most part—the Sikhs, refuse to fit into that compartmentalization.[1] Just based on their writings and how they were conveyed, Nanak and his successors saw themselves as offering something new to their fellow human beings, a path to a “better” life, sought through individual and collective actions. The last human Sikh Guru, Gobind Singh, instituted an initiated order of Sikhs, the Khalsa, which has defined the tradition ever since, even when it has been challenged or rejected by some Sikhs. The Khalsa are sometimes considered to be the mystical body of the Guru, the Guru Panth, complementing the teachings of the Sikh Gurus embodied in the sacred text, the Guru Granth Sahib.

Beyond these basic characteristics, there have been any number of interpretations, contestations, departures and fragmentations, but there is some “common core,” or perhaps a common thread, in the Sikh tradition that is often neglected by scholars outside the tradition (or those within it who want to conform to academic fashions). Such scholars seek to fit the tradition into conceptual frameworks and categories that they have been trained to accept (see note 1). This does not mean that the common core translates into a unique, eternal, comprehensive blueprint for all human beings: the issue is not one of “scholarship” versus “belief” or “tradition.” In his book, as in his other writings, Judge avoids both kinds of unquestioning acceptance and simple claims of truth or fixity. Judge is not alone in this sophistication: there are other scholars who write in a similar vein, but this is not restricted to contemporary western academia. The late nineteenth century Sikh debates that form part of his narrative are not just polemics, or responses to trauma, or attempts to fit into a new colonial intellectual paradigm, but often nuanced considerations of these issues, and Judge accords them a status often denied to them.

The point to be made here is that there are aspects of Sikh tradition that go deeper than desires for territorial sovereignty. Ultimately, the idea of the Khalsa Raj is deeper than the kingdom of Ranjit Singh, which was found wanting in many respects by early nineteenth century Sikh reformers without any connection to Duleep Singh. The idea is an ideal, grounded in interpretations of Sikh tradition that are built on the “common core” of moral or ethical foundations. Indeed, Duleep Singh sought legitimacy by promising to recover and adhere to this ideal. In an 1886 letter addressed to the Khalsa as a collective body, he promised to adhere to the “pure and beautiful tenets” of Guru Nanak, and “obey the commands” of Guru Gobind Singh.[2]

Tracing the Aftermath

Duleep Singh died in 1893, two decades after Sikh leaders began their formal efforts to “remake” the past, though arguably, also to “recover” it—many of the debates revolved around what was authentic, in terms of the message of the Sikh Gurus, with the Guru Granth Sahib and other historical documents providing only incomplete evidence and guidance. Some of those debates continued for decades after. A concerted collective effort to create a comprehensive Sikh code of conduct took almost two decades, but the code finally produced in 1945 has limitations. These efforts were overshadowed by impending political upheaval: at this time the prospect of the British retreating from imperial India became more likely, as did the aim of partitioning it to give Muslims their own separate nation-state. In these circumstances, Sikhs, who lacked any significant territory where they were a majority, almost had no place to go, ultimately throwing in their lot with Hindu-majority India. They did so with vague assurances of autonomy in that aspirationally pluralistic nation.

Sikhs were a significant part of the massive migration that accompanied Partition, and many ended up in Indian cities outside Punjab, especially the capital territory of Delhi. As the new republic of India redrew its administrative boundaries, partly to absorb princely states and partly to align those boundaries with linguistic groupings, Punjab was the last to have the process completed. A Punjabi-majority state was going to be a Sikh-majority state, which raised concerns for India’s leaders in terms of national security and territorial integrity. Much of this anxiety was actually the result of India’s accession of Muslim-majority Kashmir. In a twist of history, the Hindu ruler of Kashmir who made this decision was a descendant of the Dogras who had served in Ranjit Singh’s administration, betrayed his successors to the British, and been rewarded with that prime chunk of the Sikh kingdom.

Another factor in the process of defining—and delaying—a new Indian state of Punjab was Hindu nationalism, with slogans such as “Hindi, Hindu, Hindustan” epitomizing a majoritarian idea of India quite different from pluralistic aspirations. Again, this phenomenon had clear historical antecedents—the Jana Sangh of the 1950s which opposed a Punjabi linguistic state came from a different strand of Hindu nationalism than the Arya Samaj of the 1870s, but each strand has had difficulty in acknowledging a distinct and distinctive Sikh tradition.

The Partition and accompanying migration inflicted heavy economic costs on the Sikhs, in addition to the political uncertainties and cultural challenges that came with being part of independent India. Just as new water infrastructure during the British colonial period had given Sikh farmers opportunities in areas of Punjab that were now in Pakistan, the post-independence Bhakra-Nangal dam and new canals tapped into Indian Punjab’s remaining rivers, providing one piece of an agricultural renaissance, in what became known as the Green Revolution. New, high yielding varieties of wheat (and later rice), combined with chemical fertilizers and guaranteed purchases by an India government striving for national food security, ushered in an era of prosperity for Indian Punjab. However, this was short-lived and somewhat illusory. The production model came to rely more and more on input subsidies, environmental damage was ignored, and farmers found it difficult to move into alternative crops or occupations. The Green Revolution was ultimately a poisoned chalice for Punjab’s—mainly Sikh—farmers.[3]

Beginning in the early 1970s, access to adequate water to sustain the Green Revolution became a persistent political concern for Punjab’s farmers, especially after a tribunal award that split river water allocations between Punjab, Haryana, and Rajasthan that many rural Punjabis viewed as unfair. But Sikh politicians also invoked the idea of Khalsa sovereignty and lingering concerns with some of the wording of India’s Constitution—which Sikh representatives had refused to sign when it was finalized in 1949—in an eclectic set of demands known as the Anandpur Sahib Resolution. This document also included a proposal for much greater autonomy for Punjab, a kind of demand which has always served as an alarm signal for India’s national governments, whatever their political ideology. As for the case of Duleep Singh and the British—eloquently described by Judge—the fear is that such invocations may strike a chord with the masses, or be exploited by foreign governments, to destabilize the political order. This fear holds whether that order is based on colonization and imperial rule, or a on modern, centralizing nation-state, and no matter how unrealistic the goals that are articulated.

The Anandpur Sahib Resolution explicitly worries about the loss of Sikh identity because of Hindu nationalism, as well as the economic precarity of Punjab’s Sikh farmers. It also hints at concerns about the erosion of Sikh values in the face of modernity and material prosperity. The original Khalsa Raj of Ranjit Singh had raised its own concerns about adherence to Sikh values, leading to a complex process of “reform”—some combination of recovery and remaking—through much of the nineteenth century. During and soon after Ranjit Singh’s reign, Sikh reform movements arose which sought to shed practices that were considered to depart from the teachings of Nanak and his successors. By the time Duleep Singh reached middle age and sought a return to Punjab and to some kind of sovereignty, a vigorous social and intellectual effort (the “Singh Sabha movement”) supplemented the goal of “religious” reform and recovery. Duleep Singh was, perhaps, just a marginal figure in that process, though Judge uses his story to shed light on this effort of “uprooted transmission,” which was much more than recovery.[4] In the 1970s, another figure, coming from a completely different background than the former prince, might have remained marginal too, if not for a very different set of political maneuvers than the response of the British colonists to Sikh concerns in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The Anandpur Sahib Resolution explicitly worries about the loss of Sikh identity because of Hindu nationalism, as well as the economic precarity of Punjab’s Sikh farmers. It also hints at concerns about the erosion of Sikh values in the face of modernity and material prosperity.

Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale was a Sikh preacher who embodied a strong commitment to certain Khalsa traditions, arguably more sincerely than the politicians who drafted the Anandpur Sahib Resolution. But he was no more “mainstream” than the Maharaja-turned-English-gentleman striving to be a leader of the Khalsa, Duleep Singh. Bhindranwale was concerned about the erosion of Sikh values and a distinct Sikh (Khalsa) identity, and he blamed Hindu nationalism, but also the corruption of modernity. After Duleep Singh’s death, the British had somewhat of a two-pronged approach to dealing with potential unrest. On the one hand, Sikh and other revolutionaries were imprisoned, exiled, or executed, and even peaceful protests were initially suppressed. But the British also accommodated demands that did not threaten their rule. In particular, Khalsa Sikhs succeeded in gaining control over all significant Sikh sites of worship, including the Harmandir Sahib (mostly known to westerners as the Golden Temple), the most sacred Sikh site of all. The complex of sacred buildings surrounding the Harmandir Sahib is where Bhindranwale established a fortified presence in 1984. Arguably, the situation could have been de-escalated and diffused, but the national government chose a full-scale military assault by the Indian army, with Bhindrawale and his followers being killed, but also many innocent Sikh pilgrims. This triggered a terrible sequence of events: the assassination of India’s Prime Minister, pogroms against Sikhs in retaliation, a militant uprising in Punjab, and a decade of brutal repression in response. The losses of the Sikh community accumulated anew.

Conclusion

One should not overdraw comparisons between the late nineteenth and late twentieth centuries in Punjab, but there are recurring themes of dreams or claims of sovereignty, with sites associated with the history of the Khalsa playing a central role. Anandpur (site of the 1973 resolution) is where Guru Gobind Singh founded the Khalsa, and the Khalsa increased the symbolic weight of the Harmandir Sahib complex as a marker of sovereignty during the eighteenth century, though Guru Gobind Singh’s grandfather had built the Akal Takht (Throne of the Timeless) almost a century earlier, as a symbol of temporal sovereignty to complement the spiritual. Colonial rulers ceded a kind of sovereignty over the Harmandir Sahib and other sites to the Khalsa Sikhs. In very different circumstances in the twentieth century, a democratic government made brutally clear the limits of that sovereignty.

If not for the events of 1984 and the decade that followed, Khalistan—the now common term for a future version of the Khalsa Raj that Duleep Singh sought to recover—might have remained what it was in the years after Indian independence: a quixotic goal of a handful of diasporic Sikhs, more unattainable than anything that the erstwhile Maharaja pursued. Instead, it has become a focal point for those who were brutalized, displaced, or diminished by what happened in 1984 and afterward, a focal point for all those new losses. Much of this sentiment is concentrated, or at least has more space to be articulated, in the diaspora, where Sikhs from rural Punjab have continued to seek both refuge and opportunity. All the themes of Judge’s book continue to have new lives in this situation.

But these approaches to loss risk taking the Sikh community down an unproductive path. The material problems of Indian Punjab will not be solved by a Khalsa Raj. Political autonomy will do nothing by itself to shift Punjab’s economy out of a destructive and unsustainable trap of growing wheat and rice for India’s food security. Instead, Punjab, including its farmers, industrialists, and traders, whether Sikhs or others, has to build human capital, attract financial capital, innovate, and strive for sustainability. It is certainly possible that the ethical principles of the Sikh tradition and the Khalsa can provide a foundation for such a transformation, but it would not be an automatic process. The Khalsa Sikh reformers, who began their work before the emergence of Duleep Singh’s aspirations of recovering what he had lost, and who continued for decades after his death, used their remaking of the past to try and shape a productive future. Some of these efforts succeeded, others failed, and some have had mixed consequences.

In my reading of Judge, he cautions against simple notions of history as linear progress, or even as a causal chain of events, but also acknowledges that there are such things as ethics and justice. Delineating a path that, if actively followed, moves humans toward more ethical and just conditions for all is worthwhile. Judge’s book reminds us of the complexities of such delineation and action, and the challenge of carrying the weight of the past, along with the possible wisdom of experience that is part of that load. The current situation of Indian Punjab is dire in many respects, and neither technocratic formulas nor dreams of an idyllic past will change that. Judge’s book, while speaking of events from over a century ago, leads one to reflect on everything in between these two intellectual poles, hopefully with productive consequences—even if that is not his goal. People’s memories and the meanings they assign to them will always matter, and Judge articulates that message clearly and eloquently.

[1] See my 2001 essay for a discussion of the “Sant” category and its problematics. Note that the word “sant” comes from the Sanskrit “sat,” meaning “truth,” and has no relationship to the English/Catholic term “saint.”

[2] These quotes are from the letter, an extract from which is in Judge on page 93.

[3] An overview of this situation can be found in L. Singh et al., Economic Development of Punjab, India: Prospects and Policies (2024) and the references it contains.

[4] At the same time, this process was also not just one of remaking or imitation of the West, as argued by some—see my essay, “Who Owns Religion: Scholars, Sikhs, and the Public Sphere” (2023) for an evaluation of events of the period.