Dana Lloyd (DL): Dear Barbara, I am thrilled to begin this conversation about your book, Sanctuary Everywhere, and some of our mutual interests. I’d like to start by inviting you to unpack the broad argument of your book and relay some of the key interventions it makes in the field.

Dana Lloyd (DL): Dear Barbara, I am thrilled to begin this conversation about your book, Sanctuary Everywhere, and some of our mutual interests. I’d like to start by inviting you to unpack the broad argument of your book and relay some of the key interventions it makes in the field.

Barbara Sostaita (BS): Dana, I want to open by naming how important it was for me to form part of the theories of land working group that you and Evan Berry convened a couple of years ago. Being in conversation with you and other participants deepened my engagement with land, inviting me to think more capaciously about the Sonoran Desert and its more-than-human forms of life. Since our collaborations with each other begin with land, I want to start by situating sanctuary as emerging through sets of relations—between and among the living and dead, the human and more-than-human, the past and present, the sacred and profane. Sanctuary, then, is fragile and fleeting, emergent and mobile. I began this project by proposing that sanctuary is not a singular place, and that this practice cannot be confined to one location, that is, a church, city, university, restaurant, hospital, or safe house. But that does not mean that sanctuary does not emerge through and engage with land. I really like how Hugo Canham describes Mpondoland and Mpondo theory in his book Riotous Deathscapes, and it applies to sanctuary, too—“Located, but in motion” (14).

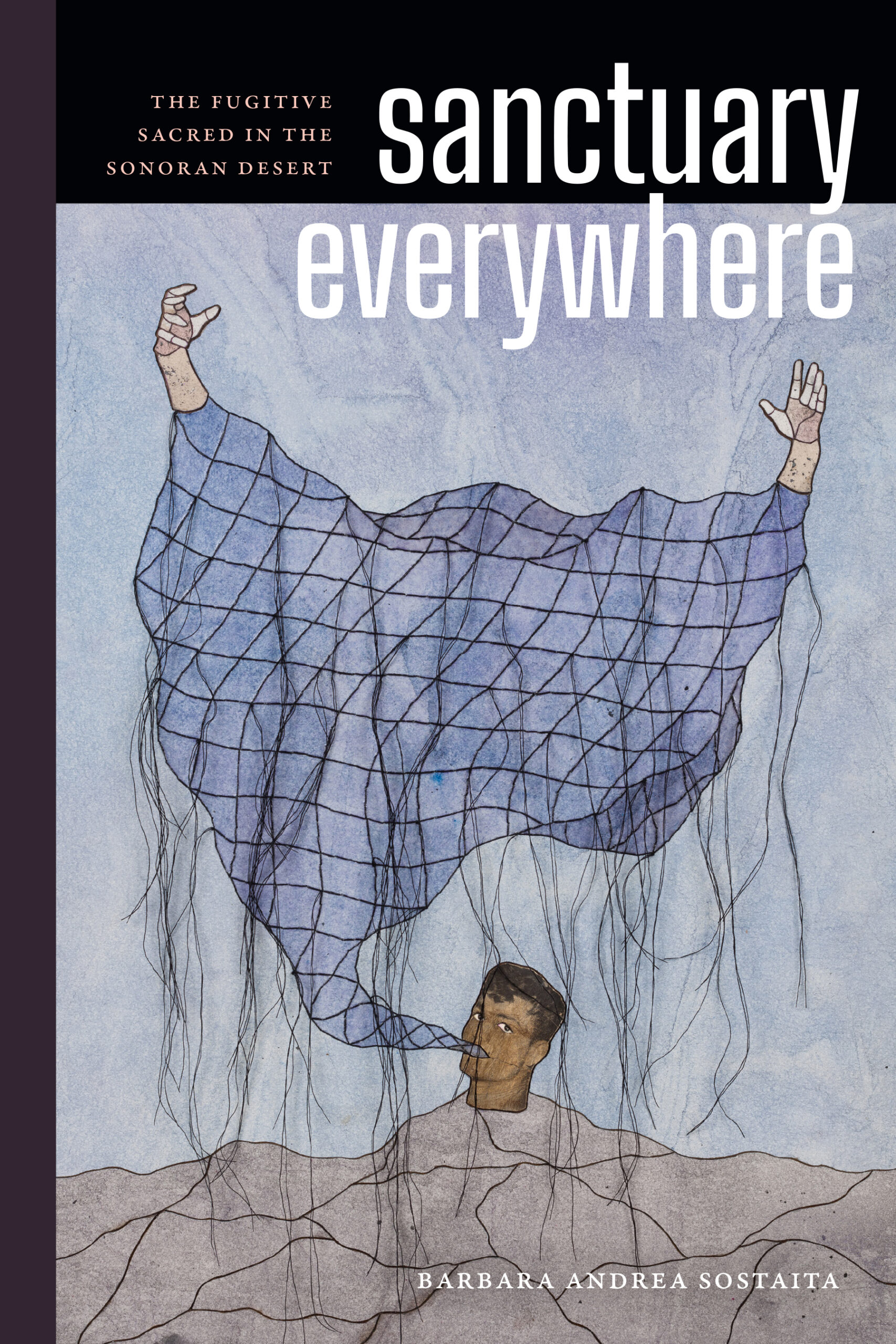

Sanctuary Everywhere traces the ways people on the move—migrants, activists, artists—engage in fugitive practices of care. It turns to four scenes: (1) moments when land and its more-than-human formations refuse or defy the enforcement strategy known as Prevention Through Deterrence, (2) when incarcerated migrants pursue illicit or forbidden touch inside detention centers, (3) when a deported nurse tends to the wounds and spiritual needs of migrants in Nogales, Sonora, and (4) when the desert’s dead restlessly haunt the living and refuse closure from humanitarian workers. It is an ethnography focused on the Sonora-Arizona borderlands, not because the border is the only site of immigration enforcement but instead because there is a long history of fugitive activity in this region. From Chinese migrants who crossed the Sonoran Desert covertly during the era of Asian exclusion to enslaved Africans who fled south to evade capture, the Sonoran Desert is—to quote Samuel Truett—a “fugitive landscape.”

I always struggle with questions about my interventions because I see myself more as a curator or maybe even a medium—an intermediate or someone who relays messages between worlds. The word “sanctuary” comes from sanctus or the sacred. And in this book, I hope to encourage scholars to think about the sacred as unruly, disruptive, and dangerous to the everyday—a fugitive movement that unsettles the profane, or everyday. The sacred refuses to recognize boundaries. It restlessly seeks escape from the profane world of policing, militarization, and bordered nation-states. In writing about the sacred, I draw inspiration from abolitionist thinkers and practitioners who are laboring towards defunding, disrupting, and dismantling the present and who see abolition not as an arrival but as an ongoing practice and process. Extending Georges Bataille’s and Michel Foucault’s theories of transgression, I consider sanctuary and the sacred as life-transforming disruptions of immigration enforcement operations, as these vibrant and ephemeral moments that interrupt the everyday. As, to draw inspiration from Angela Davis, a practice of experimentation in refusing the everyday and ordinary. If this is an intervention, it is also an inheritance. One that comes from the Black Radical Tradition and from scholars like M. Jacqui Alexander and Gloria Anzaldúa, who have made it possible for me to think of the sacred as on the move.

(DL): Thanks for this, Barbara. Reading your book, I could hear echoes of our conversations from a couple of years ago, conversations that had a similar impact on my own thinking.

In some ways, your book begins where mine ends. You talk about meandering as your method but also as the land’s (or water’s) method of resisting authority—especially state authority. I end my book with the story of the Klamath River, and how rivers are especially helpful in challenging the binary notion of sovereignty—only nation-states can be sovereign—because they do not obey state borders. I end my book with the removal of four dams from the Klamath River and you write in your first chapter that “[e]ven the dams that allegedly tamed the wild river have a life span. Concrete wears down. The water will flow again” (46).

In your answer above, you speak about sanctuary as a set of relations, but in the book, you also write about land as a set of relations. I read your “meandering method” as perhaps your way to enter into a relationship with the land of the Sonoran Desert.

So I’m especially eager to hear you talk more about this method, as your own method, as the desert’s method, and about the relationship between the two.

(BS): What a beautiful connection between our two books. Your reflections on sovereignty are precisely why I was also drawn to meandering. My method was in part inspired by Nicole Antebi’s meander maps of the Río Bravo, which trace how the water interrupted and even disturbed Mexico’s and the United States’ efforts to establish fixed borders in the aftermath of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. She shows how the river constantly refuses the state’s designs and instrumental aims. The meandering of the river, to me, pointed to how land and its many more-than-human formations defy the ambitions of states, capitalists, and “settler-conquistadors” (to cite Tiffany Lethabo-King) to tame or operationalize their sacred energies. The Sonoran Desert moves—from dry washes that fill with water during monsoons to jumping cholla that latch onto skin or clothing and javelinas that leave behind seeds as they cross borders.

When writing the book, I wanted the prose to honor these movements as well as the movements of people—which unfold alongside and through land. The people I met in the Sonora-Arizona borderlands were constantly on the move (or being moved)—traversing the desert’s underground passages, being smuggled to detention centers, relocating from one humanitarian shelter to another, visiting the sites where migrant remains were found, over and over again. As I suggest in the book, migrants and their collaborators are not fixed in place, and neither are the words on the page. My meandering method points to these detours and precarious itineraries. It honors the exit routes that humans and more-than-human forms of life pursue, their restless and unsettling movements. Meandering is a sacred movement, one that escapes comprehension and exceeds intelligibility.

I’m so grateful that you identified the meandering method as an attempt to seek or pursue relation with the desert. Like my theorization of sanctuary, relation too refers to a practice, not a destination.

I wanted the text to show that I, too, am on the move—as an ethnographer, writer, and migrant. I meander from scene to scene, inviting the reader along as I join humanitarian water drops, plant crosses for migrants, attend my citizenship ceremony, and return to Argentina for the first time in over twenty years. Édouard Glissant refers to relation as a “modern form of the sacred,” as chaotic, unruly, endlessly under construction–“a disorder one can imagine forever” (16, 133). In a sense, my meandering method owes a lot to his understanding of relation and his conceptualization of errantry—as movement that does not and cannot settle, that is circular and ongoing. At points, my chapters dwell on the paradoxes and ambiguities of practices of sanctuary without reaching a definitive conclusion or cohesive argument. I also write about the ethnographic task as one that will always be unfinished. For me, this comes from Glissant and his insistence on relation.

(DL): Thank you. If your meandering method is about relations, then your theoretical framework seems to be about relations as well. I love the idea of sanctuary as practice—could you unpack it for us? Your second chapter—”The Detained”—broke my heart, but I don’t think that was your intention. You theorize sanctuary, through instances of contraband touch in migrant detention centers, as abolitionist care work, but as we see later in the book, sanctuary and care travel with migrants across borders (“Chapter 3: The Deported”), and it is not limited to living people either (“Chapter 4: The Dead”). I guess what I’m asking is to hear more about sanctuary as a practice of care and about your relational theoretical framework.

(BS): When I began researching this book in 2017, Donald Trump had recently assumed the presidential office, and, in response, organizers across the country (and elsewhere in the Americas) were taking up the tradition of sanctuary. I learned about sanctuary homes and restaurants. I read a press release by Pueblo Sin Fronteras—a group that organizes migrant caravans—demanding Mexico declare itself a “sanctuary country” for migrants traversing its vertical borderlands. And I spoke with activists from the 1980s Sanctuary Movement (including Reverend John Fife), who explained that sanctuary continues to inform the work of organizations like the Tucson Samaritans and No More Deaths. My first questions were: Why this particular tradition? In what ways is sanctuary portable? And then, when I began to hear about the Trump administration targeting groups like No More Deaths—raiding their humanitarian camp in the desert, arresting their volunteers—and about the experiences of migrants who described living in sanctuary as a form of confinement or even incarceration, I started wondering about the limits of this tradition when it is imagined as a fixed place of protection. In the face of widespread surveillance, policing, and militarization and in a context where borders exist as “mobile technologies” (to cite my colleagues Jonathan Inda and Julie Dowling), sanctuary cannot be confined to a stable or singular place.

Instead, I propose that sanctuary is a practice and process—never guaranteed nor settled. María Puig de la Bellacasa is helpful here, describing care as the “concrete work of maintenance,” as work that entails ritual and repetition and involves touch and labor (5). As a practice, sanctuary is emergent and creative, endlessly being made and remade. In the book, I think seriously about the etymology of this practice—which comes from the Latin sanctus, meaning sacred. And though many in religious studies have let go of the binary of the profane and sacred, I find it really useful for thinking about taboos, prohibitions, transgression, and immanence or intimacy. What I find really interesting about the sacred is that it’s kept separate from the profane because of its potential to disturb and unsettle the everyday, and because sacred beings and forces move. They are slippery, contagious, unstable, precarious, and even fickle. Notably, sanctus refers to a place, person, or object that has been made sacred, that has been dedicated, consecrated, and set apart. The sacred must be made, over and over again.

In the chapter you mention, “The Detained,” I consider how migrants confined in detention centers defy prohibitions on touch. I think about touch as sacred–positive and negative, healing and harming, alluring and threatening. I consider how scholars like Émile Durkheim theorize the sacred as contagious, as eager to spread through touch and proximity. There are countless taboos on touch in the prison—even for visitors like me. In the last chapter, “The Dead,” I introduce readers to Álvaro Enciso, who plants crosses for migrants who died attempting the border crossing. He describes his project as one that “defaces” and “disturbs” the desert. For me, sanctuary emerges in these moments when taboos are disrupted, when migrants and other activists transgress prohibitions, even if only momentarily. In this way, I propose that fugitive sanctuary is at odds with law and order, incompatible with charters and petitions. When we try to instrumentalize sanctuary and incorporate it into our world of policy and procedure, we are striving to tame or master a practice that is inherently out of grasp or reach. But sanctuary exceeds us.

Lastly, I don’t think my intention was for the second chapter to break your heart. But it was to invite you to enter into a kind of intimacy with my collaborators. I did want the prose to touch you.

(DL): Yes, it has touched me; indeed, the whole book touched me, and I think it is mainly because of your relationships with your protagonists—Eva, Juana, the dead whose names you recite at the end of chapter 4—and since so much of our conversation has been about relations, I’d like to invite you to reflect on your protagonists and about the relationships you have developed with them during your work on the book. You opened our conversation by saying you see yourself as a kind of medium. I think I could hear your own voice very clearly as I was reading the book, but I also appreciate this notion of the author as a curator or medium. Maybe you could tell us a little bit about balancing story (channeling the voices of your interlocutors) and analysis (bringing in your scholarly lens) in your writing?

(BS): What draws me to ethnography is the capacity for developing relationships with people who not only reaffirm but often challenge my ideas or presumptions. For example, when I first visited Juana at St. Barnabas, I didn’t really expect to hear her describe the violences of sanctuary and how they were felt on her body—the pressure of the ankle monitor squeezing her leg, the lower back pain caused by her stillness and inactivity while confined to the church. I try to show the reader glimpses of moments when other people intervene in my analysis—like Tristan Reader warning me not to “delocate” sanctuary or Panchito chastising me for not taking photographs while conducting fieldwork. The analysis, in that sense, is relational. My scholarly lens emerged alongside the stories people told me and the arguments they themselves formed about their work. And that goes both ways—I know that Álvaro, for example, has shifted some of the language he uses to describe the desert in response to a lunchtime conversation we had about my first chapter and land’s refusals.

We learn from and theorize in conversation with each other. I did often bring in my scholarly analysis—like, once, as we were planting a cross for the dead, Álvaro showed me a cross that migrants had turned into a shrine. While crossing the desert, people had left behind coins, votive candles, and garlic bulbs, likely hoping for safe passage. I told Álvaro that this scene reminded me of what Elaine Peña in Performing Piety calls “devotional labor.” He really appreciated that term, which encouraged me to use it in the book. There were other moments during fieldwork when he said something, like describing his work as desecration, which inspired me to turn to Michael Taussig and his theories of defacement. Álvaro may not have expected me to use that word—desecration—as I did, as a sacred practice (he first saw it as the opposite of sacred), but I really enjoyed chasing these unexpected turns and theoretical meanders.

I saw myself in Álvaro—in his care for language and poetics, in his sense of being in-between, never having fully arrived in the United States yet not identifying with his homeland either. With Eva, though our situations were completely different—she was incarcerated, and I was conducting fieldwork—I understood and even shared her solitude. I met her weeks after moving to Arizona. At the time, I had no friends, family, or colleagues nearby. We kept each other company. Panchito drew me in—magnetic, charming, verbose. Spending time with him in Nogales was like being a celebrity’s groupie, and—as he says in the book—he saw me as another person in need, like the poor and wounded he tends to as a nurse. Distance makes maintaining these relationships very difficult and as I begin work on my next projects, I’ve decided that I won’t begin projects outside of the place where I live moving forward. Relationships demand presence and consistency. But I think (or at least I hope) that, in the relationships I developed in the field, we could all contribute to each other’s lives—to offer each other sanctuary, if only briefly.