In early June 2024, India completed its general elections, which resulted in a third consecutive victory for the incumbent Hindu nationalist Prime Minister, Narendra Modi. The Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP’s) margin of victory, however, was substantially lower than expected and the party failed to win a parliamentary majority in the Lok Sabha, or lower house of parliament. The change in the margin of victory marks the return of coalition politics, as Modi must now rely on allied parties to form the new government under the National Democratic Alliance (NDA), which includes numerous center and right-wing parties. Conversely, the Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA), led by the primary opposition party, the Indian National Congress (INC), stunned many observers as it secured a greater number of seats than expected. The demise of the INC and its leader Rahul Gandhi, the great-grandson of India’s inaugural prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, appeared to have been greatly exaggerated.

These election results produced a sense of jubilation amongst Indians who are against the politics of the Modi government. On social media and in news stories, people celebrated that Modi was “cut to size,” but more significantly, that Indians had reclaimed their “democracy” in spite of significant electoral malpractice. Within days, a plethora of analyses from Indian academics in particular circulated and proclaimed that something had fundamentally changed in India. Some argued that this election was a return to “a disinterested vision of the good society” over one that was a “politics of self-interest,” while others spoke of how “the pall of suffocation created by a decade of Modi’s strongman style…has lifted” and that this election “affirmed pluralism over populism.” The election, thus, was viewed as a “vote against hate.” Perhaps the title that succinctly summarized most reactions was that the elections brought “hope, even in defeat.” Therefore, even though the BJP retained power, the failure to reach its dominant majority in the 543-member Lok Sabha—‘ab ki baar char sau paar’ [This time with over 400 seats] as Modi’s campaign slogan went—signaled hope for Indian democracy as it was presumed that the relationship between state and society could undergo repair as the latter could renew the state.

The National Symbolic

In-depth electoral analysis and judgments of the recent Indian elections abound. Yet, is it possible to read these initial moments of hope as indicative of an Indian “National Symbolic”—what Lauren Berlant has defined as some “tangled cluster” of “the juridical, territorial (jus soli), genetic (jus sanguinis), linguistic, or experiential” that transforms individuals into national subjects? (5) The National Symbolic produces fantasy and, in particular, “a fantasy of national integration, although the content of this fantasy is a matter of cultural debate and historical transformation” (22). How do the celebratory, and indeed, jubilatory, declarations in response to the recent elections demonstrate an ongoing desire for an integrated Indian form? And how might that national fantasy affirm, rather than repudiate, Modi and his politics? We contend the celebration of Indian political forms—citizenship and the constitution, for example—reveals the perpetuation of an Indian national fantasy while it disavows the violent divisions that produce the very space of the nation.[1] Put differently, hope reaffirms the life and the narrative of the nation—signing and countersigning an Indian history, both a singular and plural one. Our goal, in contrast, is not to provide a more inclusive understanding of the Indian national fantasy, but to consider the theoretical underpinnings of the post-election relief that continue to make India a particularly powerful object of desire.

If this celebration, this hope, is tethered to an Indian national fantasy, what is this fantasy with all its multiple and contradictory meanings? For most liberal-left Indians, Modi’s tenure as prime minister since 2014 violates India’s foundation as a tolerant, multicultural nation that—while not perfect—strives towards a democratic and secular form. This tolerant form of India gains its coherence against the religious fundamentalist or the orthodox, which is known, notoriously in the historiography of South Asia, as the semiticization of Indian traditions—in which the introduction of proselytization and the assertion of religious difference during the colonial period created a “semitic” form against a tolerant “Indic” one. Numerous scholars have demonstrated that this racist framing accrues numerous adherents across the political spectrum. Sustained by historical analyses that privilege the fluid and multiple, national fantasies around India are thus bound to tolerance. It is a tolerance that functions in concert with “the will of an interventionist modernizing state in order to…supply, in the name of ‘national culture,’ a homogenized content to the notion of citizenship” as Partha Chatterjee writes—an integrated, whole, and unassailable national body.

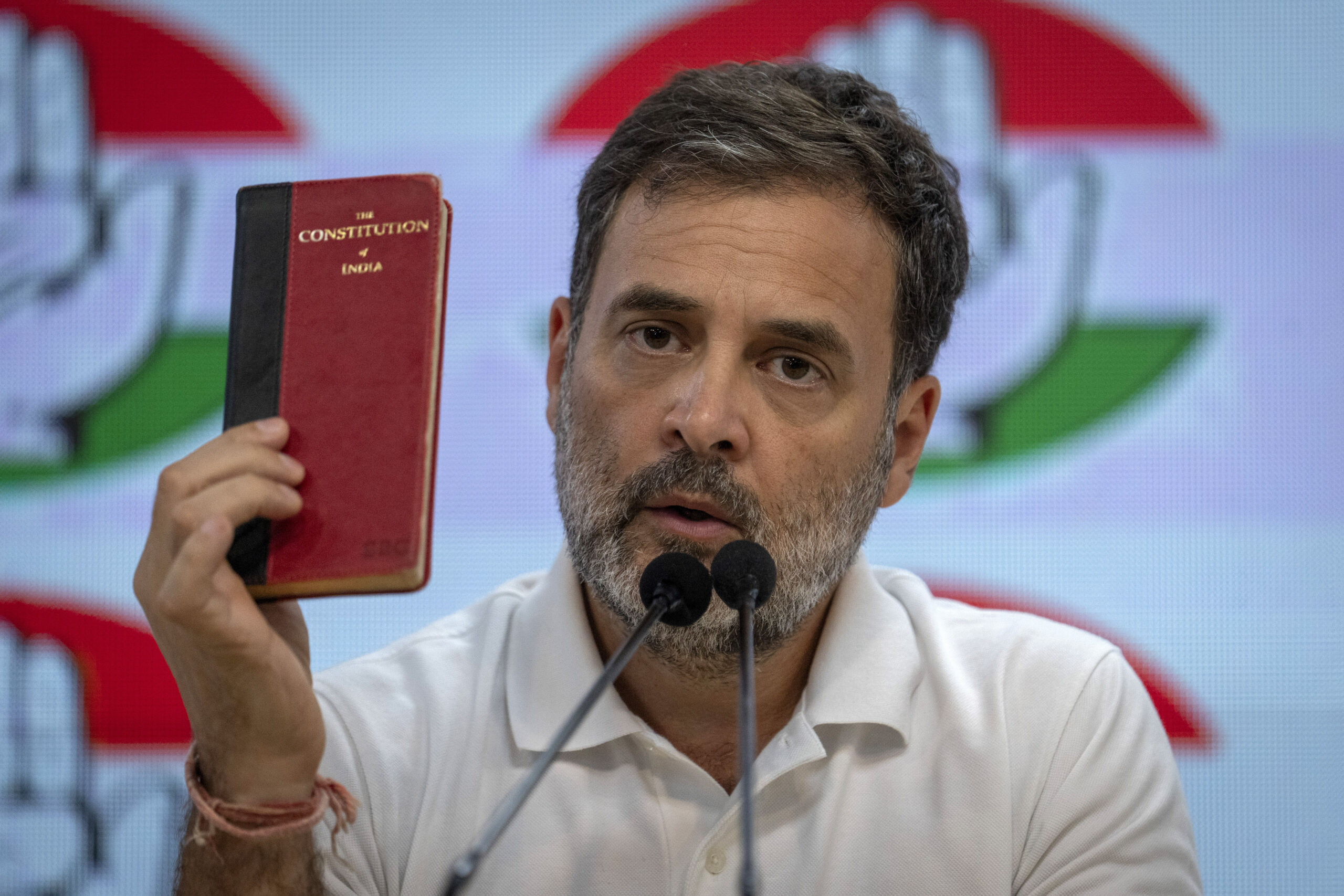

The Role of the Indian Constitution

The Indian constitution plays a significant role in this national fantasy, and it certainly was invoked a number of times during the 2024 election. Rahul Gandhi appeared in a press conference with the constitution in hand; reports later commented on how sales of the constitution have skyrocketed since. After his victory, Modi, too, called the constitution a “guiding light.”

One reason for the Indian constitution’s critical role in national fantasy, especially on the liberal-left, is because of Indian federalism: the distribution of powers between the national government and the different states’ governments creates a political form that allows for the possibility of tolerance and inclusion for diverse peoples. To take one example, in his theorization, Partha Chatterjee contends that the federalism enshrined in the Indian constitution coupled with the unique character of Indian citizenship does not allow for nation-people-state to be collapsed together to create a whole integrated national fantasy. There can be no singular National Symbolic, although the BJP constitutes an attempt to create one. Instead, in India, Chatterjee contends we find remarkably diverse political communities that are “peoples-nation”—political communities not integrated into the nation-state, but in tense relation to the nation-state. This separation provides an opportunity for a redemptive politics that is tolerant of numerous narratives and peoples. For Chatterjee, this is the case because of the structure of India’s postcolonial democracy in which formal citizenship was granted to all before their inclusion in civil society, creating, what Chatterjee calls, an alternative political society. In short, the bourgeoisie are dominant, but not hegemonic.

The BJP’s ability to triangulate nation-state-people into a unified national fantasy, then, is countered by federalism and political societies, such as regional populist parties. But beyond these regional parties, Chatterjee argues that what is needed is a counter-narrative to Hindu nationalism’s claims to cultural homogeneity to bind regional mobilizations together in the center, “a vibrant federal republic.” Such a narrative would realign the relation between peoples-nation and nation-state by making it plural with “several civilizational narratives” (109).

In a strange twist, the very impossibility of unified India—the lack of hegemony—becomes a celebrated feature of India, integrated into the nation itself, rather than calling India into question. In their very impossibility, India’s constitution and democratic culture become redemptive, always already tolerant and inclusive. Chatterjee, therefore, reinscribes the very national fantasy he purports to critique by appropriating the fundamental deadlock in the national fantasy by making it plural and offering a more inclusive and hopeful narrative for India.

Following Chatterjee’s analysis, it is easy to see why the return of coalition politics was celebrated in the aftermath of the election. Coalition politics signals the possibility for coalescing a counter-narrative of peoples-nation and, therefore, a renewed sense of hope that functions within the Indian National Symbolic, no matter India’s sordid history. As Shruti Kapila stated, there was “new-found excitement at the return to old-style political jockeying.” The return of the old India thus becomes the promise of the new India. For Chatterjee, too, “It is time to restore [coalition politics] to its proper place at the centre of our political life.” Restoration and return signal hope for a better India to come—one that was always there.

Chatterjee, therefore, reinscribes the very national fantasy he purports to critique by appropriating the fundamental deadlock in the national fantasy by making it plural and offering a more inclusive and hopeful narrative for India.

Against this hopeful excitement that creates a theoretical distinction between people and state, one must ask: Why focus on “India” at all, especially when there are political movements that reject the idea of India and the fantasies it generates? Why, then, do academics continue to provide unifying narratives for India, reinscribing the aims of a nation-state? At what point do we have to rethink the constant attempt to narrate the history of the Indian nation-state-people(s)? Do we need only more robust histories of the diversity and tolerance of India and its constitution? Or do we have to question the very logic of history since the national imaginary cannot be reduced to historical content—plural or otherwise–but is, instead, history itself? These are especially important questions since, as Rahul Rao writes, “Calls to protect the Constitution cannot mean much to those who do not wish to be governed by it – unless the Constitution can contemplate a process by which it will no longer be applicable to unwilling subjects.”

Recall that this is a constitution that has entrenched India’s colonial occupation of Kashmir and cemented the second-class citizenship status of Muslims in India. In an article written before he was arrested, the Muslim activist who was involved with the anti-CAA and anti-NRC protests in India, Sharjeel Imam, writes of how the “dismal figures among Muslims in relation to poverty, education, employment and political representation clearly demonstrate the lack of foresight regarding the minority issue during the constitution-making process.” He says that this occurred because of the articulation of the country as Bharat (a geographic imaginary derived from Sanskrit texts), which “reflects an exclusively Hindu imagination of Indian history” as well as the lack of safeguards for Muslims in terms of representation, cow protection, and finally, the definition of “schedule castes,” which excluded Muslims and led them to “further impoverishment, as they are hardly supported by any relevant programs for affirmative action at the central state level.” The very foundational moment of India then is premised on exclusion and the binding together of people-nation-state, even if scholars try to imagine otherwise. This binding reveals that the very distinction between the “state” and “political society” that makes it possible to locate hope in the latter is difficult to sustain.

Communalism and Coalition Politics

Another recurrent theme amid the celebrations was that the election revealed the limits of communal politics—a politics embodied by Modi and the BJP. During Modi’s re-election campaign, he repeatedly made a number of remarks against Muslims in India, accusing them of being “infiltrators” that depleted resources available to Hindus in order to galvanize his Hindu base. Against this Hindu-nationalist ideology, the return to coalition politics came to be seen as a return to an earlier and more tolerant secularism.

A wider historical view reveals anti-Muslim or minority hate or policies in India are not the sole property of the BJP; such exclusion has defined Indian politics since 1947. The Congress Party has engaged in communalism, and served as a source of violence or domination for minorities, including Muslims, Dalits, and Sikhs, or the occupied in Kashmir. During the election, the Indian National Congress did not directly address the Muslim question in India. In the press conference after election results came out, Rahul Gandhi thanked “the poor and marginalised people who came out to save the constitution. Workers, farmers, Dalits, adivasis [Indigenous] and backwards have helped save this constitution.” It was not lost on Muslims that they were not mentioned, despite the country’s 200 million Muslims coming out in droves to vote for the INDIA alliance, led by the Congress Party. The situation in India is such that an opposition party, ostensibly a party that is against the BJP, cannot even mention Muslims or address their fears and concerns, knowing that it will isolate India’s predominantly Hindu population.

A wider historical view reveals anti-Muslim or minority hate or policies in India are not the sole property of the BJP; such exclusion has defined Indian politics since 1947.

Anthropologist Irfan Ahmad told Al Jazeera English, “Since 2014, this electoral circus has passionately been staging Muslims as a threat against which people are asked to vote. While the BJP issues the threat openly, the non-BJP parties do implicitly: That is by remaining silent. No party has the courage to talk about the violence done to the Muslims.” Sikhs, too, have been violently targeted. Yet this violence was met with silence in the election across India even with the continued criminalization of dissent, arbitrary detentions of foreign nationals, as well as state-orchestrated murder abroad.

Yet a politics of hope that centers an Indian national fantasy means that amidst the flurry of pieces in the wake of the elections, no demands were made of the Congress party or the INDIA alliance to take stock of its communal past and present. Instead, the past and future of India always redeems the violent exclusions in the present. We must ask: If hope remains tethered to an Indian future, is the current iteration of anti-Hindutva politics rooted in a concern for the oppressed and the excluded? If so, how does such a politics contend with the Indian National Congress and India’s “secular” or “liberal” political formations without further entrenching an Indian national fantasy? To be sure, many privileged, upper caste liberal Indians have been embarrassed by the authoritarianism and Hindu nationalism of the prime minister who has harmed the national fantasy of a “democratic India.” The hope that stems from the election is particularly powerful and seductive for them since it keeps alive the “Incredible India” brand as it provides a route to self-correction: India can return to its original promise, improvements can once again be made.

Against hope, then, it might be time to interrogate these fantasies. If citizenship is marked by exclusions and colonial inclusions (Kashmir, Sikhs, and others), rather than formal granting and the creation of political societies, then India’s impossibility cannot be redeemed in coalition politics or counter-narratives. If violent exclusion and then forceful integration is at the center of India, why does it and its constitution remain the desirous object of history? How can one detach oneself from a hope and world that is not working? To detach oneself is not to escape fantasy altogether. To undo the world while making another, Berlant writes, “requires fantasy to motor programs of action, to distort the present on behalf of what the present can become” (263). But the fantasies generated by the Indian National Symbolic serve to install a singular vision of politics by seamlessly binding together the present with past and future in the promise of tolerance that always eludes.

[1] We draw here from Lauren Berlant, The Queen of America Goes to Washington City: Essays on Sex and Citizenship and Manu Goswami, Producing India From Colonial Economy to National Space.