The promotion of April 3 as “Punish a Muslim Day” brought considerable alarm and concern to Muslims in Europe and North America. It is unclear who created the flyers, which were circulated by mail to several predominantly Muslim communities in Britain in March of this year and spread to other countries soon after, but they are indicative of a climate increasing hate crimes and discrimination against Muslims and the increased volume of Islamophobic rhetoric in politics. In the face of Islamophobia’s reductive fear-mongering and will to collective retribution, it is tempting for liberals to invoke a love for the persecuted in their general humanity. However, coming to terms with the diffuse workings of Islamophobia reveals the limits of professing ecumenical allyship, and of the frameworks for distinguishing responsibility under the contemporary security state.

The “Punish a Muslim” phenomenon exemplifies the layering of conceptions of the other conceived within the imaginary of a community wronged. Purportedly appearing in Britain in March, a series of fliers declared their support for vigilante action against Muslims, ranging in reward from verbal harassment, to sexual assault, to acid attacks, to the destruction of Mecca. That the flier’s idiosyncratic presentation led some Muslim commentators and comedians to take it as a joke. It would indeed be difficult to judge its seriousness without knowing who made it, and on social media it could potentially call to anyone to find a Muslim at hand to punish. Crucially, it also does not state what Muslims had done to merit punishment. It rather presumes a world of real and imagined violences attributed to Muslims, of a general and inchoate sense of the problem of Muslim religious difference so often expressed in blunt and subtle forms.

The idea of Muslims’ shared culpability emerges strikingly in a recent essay by Bari Weiss, the New York Times’ opinion editor. The piece is noteworthy both for its proximity to the crude “Punish” phenomenon and for how it implies the same collective guilt with the apparent sobriety of a journalist’s report from the field. Weiss describes the brutal murder of Mireille Knoll, a Holocaust survivor, in Paris, which the president of France and other officials have called an anti-Semitic hate crime. After detailing other attacks by young Muslim men against older Jewish women, Weiss points to surveys that indicate disproportionate anti-Jewish sentiment among Muslims as opposed to France at large. Weiss does not state how a community’s prejudices implicate it collectively in the violent crimes of individuals. She does not ask what effects anti-Muslim sentiment in France has on the dispossession and marginalization of Muslims there, or the nation’s participation in the US-led war in Afghanistan that has led to tens of thousands of civilian deaths. The point here is not to propose a model to correctly parse personal and group culpability, but to consider why and how some complex situations of precarity and violence elicit the undifferentiated application of collective responsibility, while others do not. Contrast William Connolly’s descriptions of the assumption that black urban crime in the US is pathological to Talal Asad’s illustration that crimes committed within the work of the security state are only adjudicated individually, if at all (Connolly, 40-74; Asad, 20-38). These default accounts of collective and individual culpability are shaped by the imaginary of the confrontation of crime and terrorism, which Weiss marks with Muslim religious difference.

Weiss’ commentary on community relations in France evinces a view of global Muslim ritual danger. She notes several reports of the perpetrators of violent crimes pronouncing the Arabic formula of takbīr, that “God is greatest”. Takbīr is a fundamental part of the daily ṣalā prayers and a marker of Muslim soundscapes around the world. While Muslims do not all practice religion the same way, the takbīr is one of that practice’s clearest significations, audible practically anywhere among Muslims. Both in its specifically-Muslim sacredness and everydayness, Weiss is promoting a trope that Muslims’ address to the divine should inspire fear in others. The association of non-Christian religious ritual with shocking violence has an extensive colonial history. However, here Weiss pairs this sign of Islam with another universal, that of anti-Semitism itself, reconfigured in every generation, “the oldest hatred in the world”. Even if this is true, anti-Semitism is not present in all places and times equally, and its intensification in the recent centuries of modern European nation-building culminating in the Holocaust is obscured in Weiss’s imaginary of timeless forms of danger, in which those who “shouted” takbīr were “apparently animated by the same hatred that drove Hitler” (Mufti, 37-90).

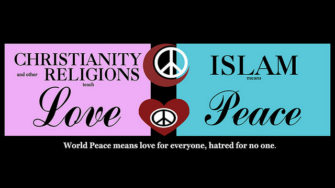

Unfortunately, faced with a fear of Muslims that looks for complicity, guilt, and punishment in Muslim life anywhere, it is difficult to imagine liberal responses that move beyond the gestural. Leading up to April 3 media reports focused on the coalescence of opposition to the “Punish” discourse under the hashtag #loveamuslim. Because #love is reacting to #punish, it shares applicability to Muslims in aggregate, which is perhaps understandable. However, it also shows the limits of our present conceptual resources in countering Islamophobia, particularly in an “interfaith” context. For one, “love” as universal and transcendent has a distinct Christian patrimony, which while this does not present a problem in and of itself, it does not ask what non-Christians might want anti-prejudice undertaken with them to look like. Furthermore, “showing love” in the face of one potentially menacing manifestation of aggression does not yield up alternatives to the policies of targeted surveillance, entrapping prosecution, and intermittent warfare that keep marginalization, extremism, and Islamophobia in cycle together.

Non-Muslims who want to respond critically to the routinization of this kind of politics should begin not by presuming intimacy with our Muslim neighbors for the sake of showing our goodwill, but by first asking ourselves some questions. What forms of mutuality does pluralized common life require? How can we relate to others as individuals? How might we also make common spaces for others to constitute communities within and without us? How can we recognize and respond together to different forms of biological, socio-political, and historically-contingent vulnerability? How can we respond to violence with justice?